On the morning of Keon Clark’s 34th day in jail, he rode a bus packed with other inmates, past scrap yards and factories along the Mississippi River, to another jail in downtown St. Louis, Missouri. When the bus arrived, a sheriff escorted the detainees to a bare holding cell. Most of the people in the cell, including 18-year-old Keon, were charged with misdemeanors—criminal offenses carrying sentences of less than a year in jail. Few in the room had a lawyer.

Across the street, at the 22nd Circuit Court of the State of Missouri, presiding Judge Calea Stovall-Reid swiveled her chair toward a monitor perched on a lectern behind her bench. She switched it on, and the back wall of Keon’s crowded holding cell appeared on the screen. The detainees took turns on a two-way video call with Stovall-Reid from across the street—a practice intended to speed up the legal process for less severe crimes—as she read to each inmate their charge, bond, and next court date. Some were making their first court appearance after spending a couple days in jail, even though they had never stepped foot in a courtroom. Others had been held for weeks, even months, with neither enough cash to cover bond nor an attorney to request a reduction.

The courtroom gallery was completely empty save for Sherry Prater, Keon’s mother and a home health aide. Sherry, a mother of five, couldn’t afford the $500 bond to get Keon out of jail, not with rent due at the end of the month. Nor the alternative option: $350 for an ankle-monitoring bracelet that incurred daily payments of $10. When Keon appeared on screen, Stovall-Reid asked Sherry if she’d like to see her son.

For pre-trial defendants like Keon Clark, a lawyer can be the difference between waiting in jail or at home.

As the sheriff brought Keon into the courtroom in handcuffs, Lynne Perkins, a criminal defense attorney, was in court on a separate case. His timing was fortuitous. Perkins, on Stovall-Reid’s request, spoke with Keon and his mother in the defense’s corner. He agreed to take Keon’s case pro bono.

With Perkins by his side, Keon explained to the judge that he and a friend were walking back from school one afternoon, when his friend suggested they break into a vacant house on the way. The house, as it turns out, was not vacant. Keon was arrested, booked, and charged with trespassing—his first ever run-in with the criminal justice system. “Are you retarded?” Stovall-Reid asked. “Why would you do that?” Keon shrugged: “I was stupid.”

Sherry never received a form to apply for a public defender to represent her son while he waited in jail for his first court appearance to arrive. Keon told me he filled out three on the advice of an older inmate, but never heard back. (St. Louis’ public defender office does not have any record of Keon applying.) To be poor, jailed, and unrepresented is a common reality for misdemeanor defendants across the country. And in St. Louis, the problem has only been exacerbated by a public defender-backed initiative to provide better representation for felony defendants. Faced with crippling workloads, the office took proactive steps to turn down most misdemeanor cases, effectively leaving hundreds of criminal defendants like Keon without a lawyer.

The right to counsel is enshrined in the Constitution, but the question of who exactly enjoys that right has been subject to more than a half century of arbitration: In 1963, the Supreme Court ruled in Gideon v. Wainwright that states must provide lawyers for felony defendants unable to afford one on their own. A subsequent decision extended that right to people charged with misdemeanors. Most recently, in 2002, the Supreme Court decided in Shelton v. Alabama that anyone facing the possibility of incarceration, which includes probation sentences, is entitled to the right to counsel.

But a growing collection of research suggests that jurisdictions across the country routinely fail to provide adequate representation for misdemeanor defendants. According to Erica Hashimoto, a University of Georgia Law professor, gargantuan caseloads combined with paltry funding have left the nation’s courts too overburdened to comply with Shelton. The result: a full-blown constitutional crisis, with America’s poorest citizens suffering the consequences.

“No Supreme Court decisions in our history have been violated so widely, so frequently, and for so long,” remarked Chuck Grassley, the Republican from Iowa, chairing a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing in May. “America’s indigent defense systems exist in a state of crisis,” former Attorney General Eric Holder said in an address commemorating the 50th anniversary of Gideon.

A Pacific Standard review of cases opened in Missouri’s 22nd Circuit during the first six months of 2014 identified more than 170 cases of defendants pleading guilty to misdemeanors without ever seeing a lawyer. Most were presided over by a single judge, Thomas Clark.

Case details hint at defendants’ impoverished backgrounds, and crimes arising from ends unmet. Several cases involve defendants trespassing at public housing facilities. Some defendants snagged food or toiletries from department stores. One man spent 120 days in jail for stealing laundry detergent from a dollar store.

“At the heart of it, the crime is being poor,” says Thomas Harvey, executive director of Arch City Defenders, a holistic legal services organization that has studied the representation gap in St. Louis’ state court. “Now, these defendants can’t get a lawyer even though the state is supposed to appoint one. They plead to a misdemeanor to get out of jail, and they leave poor, maybe with no job, no housing, and if they have mental-health problems, no connection to treatment.”

American Bar Association guidelines advise that anyone accused of a crime should talk with a lawyer before their first appearance in court. For pre-trial defendants like Keon Clark, a lawyer can be the difference between waiting in jail or at home. For defendants taking their case to trial, it’s nearly unthinkable to navigate the criminal justice system without a lawyer’s guidance. A misdemeanor conviction can have life-altering consequences—restricting employment and housing options, even triggering deportation.

In one remarkable case, a man was held for 30 days for driving with a revoked license, unable to pay the $2,500 to get out. He pled guilty, assuming it would get him out of jail. Instead, Judge Clark sentenced the man to another 60 days. As the defendant languished behind bars, he lost his job as an auto mechanic, fell behind on rent, and started taking medication for depression and anxiety.

While Keon sat in jail, he missed the start of the fall semester. On the day that he was picked up, Sherry expected him to be at her mother’s house, looking after his cancer-stricken grandmother. Instead, she received a call from the police department informing her that Keon landed himself at the Workhouse, a notoriously rough jail at the north edge of the city. “If all he has is a trespassing charge, why is he at the Workhouse? He’s just a kid,” Sherry says. “I was completely dumbfounded by the process.”

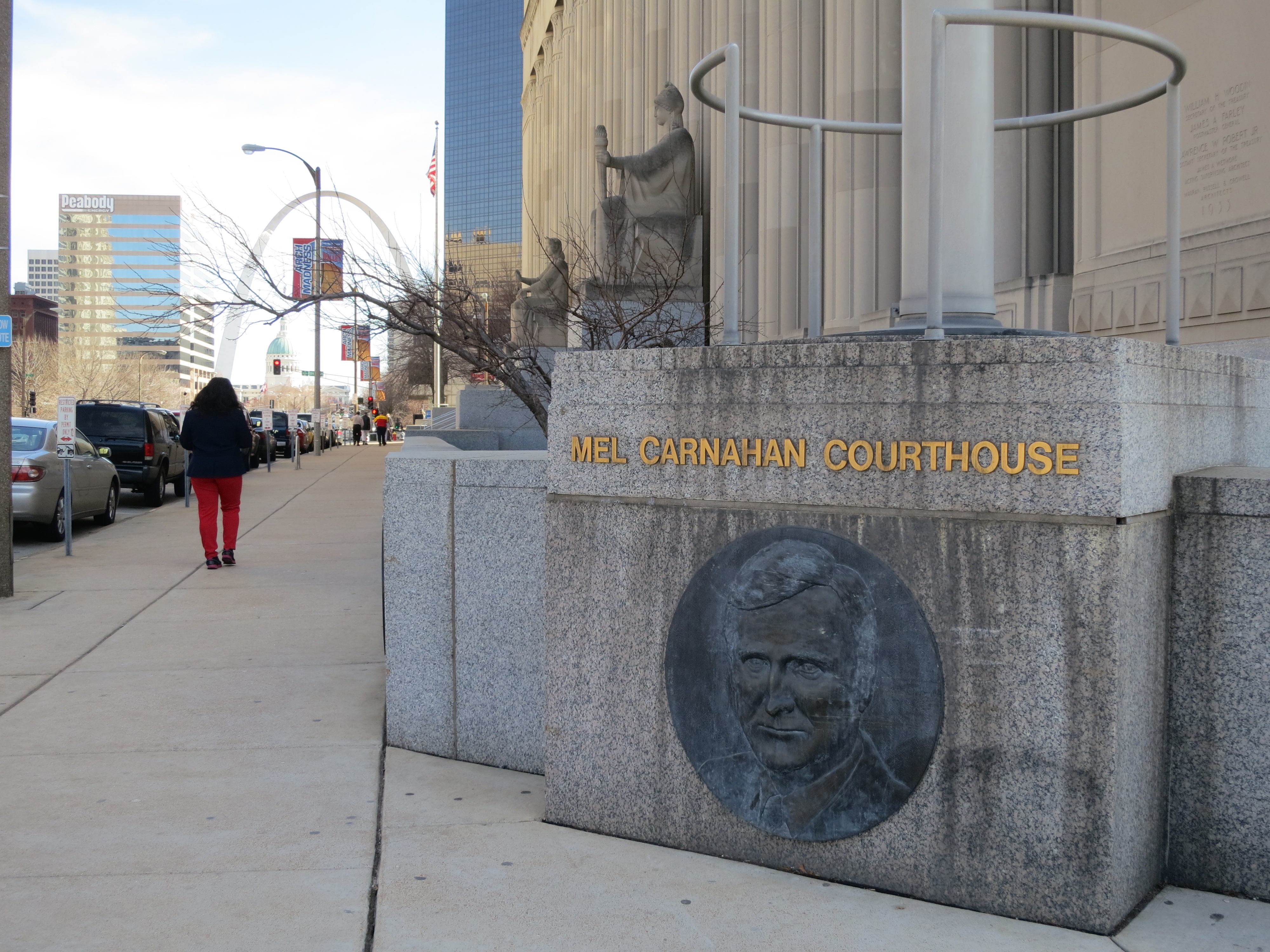

The public defender office in St. Louis occupies the sixth floor of the Mel Carnahan Courthouse downtown. The reception area looks like a dentist’s office—complete with magazines and toddler toys. An old vault has been converted into a wardrobe for clients: dress shirts, pants and shoes of all sizes, and enough neckties to stock a Macy’s. Nameplates on the attorneys’ office doors are decorated with smatterings of lawyer humor, like a cat peering through window blinds, telling its interlocutor to “Come back with a warrant,” or a baby chick ensnared in a police line-up of marshmallow Peeps. Inside, the staff attorneys sit behind desks with views of high-rises and green spaces, the Gateway Arch glimmering in the distance.

“Unfortunately, we don’t have much time to look out windows,” says Mary Fox, district defender for the 22nd Circuit Court. Fox’s nameplate is paired with a print-out of Disney’s Robin Hood, a spirit animal in name and conviction. She has gray, cropped hair and wears thin-framed glasses.

As head of St. Louis’ public defender office, Fox manages a staff of 29 attorneys, eight support staff, four investigators, and one (unpaid) intern. Half of Fox’s attorneys have less than five years legal experience; about a quarter have less than two. Nearly all of them are saddled with law school debt. When Fox accepted her position in 2007, she inherited an overworked and underfunded workforce. “Given the resources we’ve been provided, it is very difficult for us to do our jobs,” Fox says.

The St. Louis public defender office is part of the Missouri Public Defender System, a statewide agency that has struggled for years to obtain additional funding. Missouri ranks 49th in funding for indigent defense services. Salaries are among the lowest in the country; starting attorneys take home $38,500 a year. On top of that, the state’s standard for public defender eligibility is the country’s strictest. A Missourian making $11,000 annually would not qualify for indigent representation. As the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported, someone could qualify for food stamps, but not a public defender.

An American Bar Association-sponsored study of Missouri public defender workloads concluded that the state’s system would need to increase its workforce by 291 attorneys, or 70 percent, to devote the necessary time to provide effective assistance of counsel. Missouri, however, has not meaningfully increased MPDS’s budget in years. Meanwhile, the state’s current administration has increased prison spending by $55 million. “Tough on Crime is an easier sell than Help People Charged With Crimes,” Fox offered as an explanation. In August, MPDS Director Michael Barrett published a scathing letter to Governor Jay Nixon, blasting “Missouri’s contempt for the rights of poor people.”

At the beginning of Fox’s tenure, attorneys in St. Louis typically handled more than 100 cases at a time. When preparing for trial, it was not uncommon to work 80-hour weeks. (St. Louis takes more cases to trial than any other jurisdiction in Missouri.) The work was brutal. “If you’re on trial for murder this week and robbery next week and rape the following week, and then you finally have a week off, you’re just exhausted,” says Richard Kroeger, a 10-year veteran of MPDS. “You just see this never-ending cycle of, ‘I’m going to be in trial forever.'”

A study by George Mason University described the state’s caseload crisis as “one of the worst in the nation,” so severe that it “has pushed the entire criminal justice system in Missouri to the brink of collapse.”

Sisyphean workloads take a toll, not only on attorneys, but the clients they represent. Imagine an understaffed kitchen during a dinner rush. Food arrives late or shabbily prepared. Completely swamped by their workloads, Missouri’s public defenders struggled to meet professional standards for their clients. Jail visits lasted minutes. Witnesses went ignored. In one felony case, Fox recalled, an attorney failed to obtain 911 dispatch tapes that would have proven a defendant’s innocence. “Could my attorneys do everything they were supposed to do? Realistically? No. Were they good lawyers who were trying to do everything they could do? Absolutely,” Fox says.

But effort is little comfort to those most in need of quality representation. In the course of reporting this article, I encountered several defendants skeptical of any government-funded lawyer. The pejorative “public pretender” was thrown around. One man, charged with stealing copper wiring, explained his distrust saying, “They work for the state.”

In order to remedy this perception, Fox made it her mission to bring caseloads down, so her attorneys could devote more time to each client. Fox identified misdemeanors and probation revocations as areas where attorneys spent too much energy with little effect on case outcomes. (At the time, two attorneys handled all the misdemeanors in the office, which surpassed 1,000 cases a year.)

Empowered by a 2012 state Supreme Court decision granting public defenders the ability to refuse cases when workloads were too high, Fox eliminated certain types of misdemeanors from public defender consideration. A year later, when the state legislature passed a stipulation that judges must sign off on any effort to turn away defendants, Fox worked with the local bench to keep misdemeanors out of her office.

In Missouri, someone could qualify for food stamps, but not a public defender.

Alongside her legal wrangling, Fox made another change to ease defender workloads. In the past, public defenders in St. Louis interviewed every single criminal defendant who showed up to court to determine whether they were eligible for representation. Fox ended that practice in 2012, removing the burden of ensuring the right-to-counsel from her office and handing it to the courts.

Her efforts paid off. From 2012 to 2014, St. Louis’s public defender caseload dropped by more than 40 percent. The number of misdemeanor cases fell 80 percent. Other public defender offices, like those in New Orleans and Miami, have also established protocols to control caseloads. No other district in Missouri, Fox acknowledges with pride, has come close to St. Louis in relieving its attorneys’ work burden. At the same time, hundreds of misdemeanor defendants were left in jail without representation. Fox also acknowledges this uncomfortable fact.

“Did we manage our caseloads at the expense of people charged with crimes? Absolutely,” Fox says. Though the truth sounds cold, Fox maintains that it is her job to ensure effective representation for her clients. “There are people who fall through the cracks, but it’s the judge’s responsibility to inquire with them. We work for our clients, not the courts,” she says.

Fox’s logic has its defenders. Thomas Harvey, of the Arch City Defenders, described her decision as “courageous,” but added that he’d also like to see Fox call for the dismissal of unrepresented cases. “Without the second part, she’s taking a stand on behalf of her attorneys, but not advocating for people who are locked up without a lawyer.”

A spokesperson for the Missouri’s 22nd Circuit Court says the court is “confident that it has conformed” with state laws regarding indigent defense services, but did not respond to broader questions about the constitutionality of the court’s practices. Michael Barrett, Fox’s boss, put it this way: “It’s a choice between evils. If we refuse to represent someone, it’s so we can provide adequate representation to someone else. In one instance, someone receives his or her Sixth Amendment rights and in another, they don’t.”

On the day of Keon’s first court appearance, the criminal defense attorney Lynne Perkins requested for Keon’s release on his own recognizance. Sherry would act as her son’s sponsor. The terms were simple enough: go to school every day, avoid the area of arrest, and stay out of trouble.

As he exited the courthouse, I asked Perkins if Keon would’ve spent so much time in jail had a public defender taken his case. Perkins, a former public defender himself, responded without pause: “No way. Public defenders went to law school. They passed the bar. They would’ve made the same request I did and gotten him out a long time ago.” Perkins continued: “Everybody deserves a lawyer, even if it’s for a misdemeanor.”

Keon was released the next day. A couple weeks later, Sherry Clark sat outside her home on the north side of the city, getting ready to go to work. Keon was at school. Every other house on the block was vacant. We talked about lawyers, jail, and the criminal justice system. But mostly, we talked about her son. “Keon, for the most part, he’s quiet,” Sherry says. “But I know when he gets around his friends, he’ll get a little rebellious. We all were teenagers at one point.”