You probably like parks. You assume everyone feels that way. You are wrong.

As the National Park Service prepares for next summer’s centennial, I’ve been thinking about the people on the wrong side of national park history. A recent tweet from Danielle Brigida, who works for the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, shows that such objectors were intense and taken seriously in their time.

Proof that we've come a long way. Here's a 1920 ad campaign that didn't want to save Malheur Lake. pic.twitter.com/I6kYMg9D7X

— Danielle Brigida (@starfocus) October 13, 2015

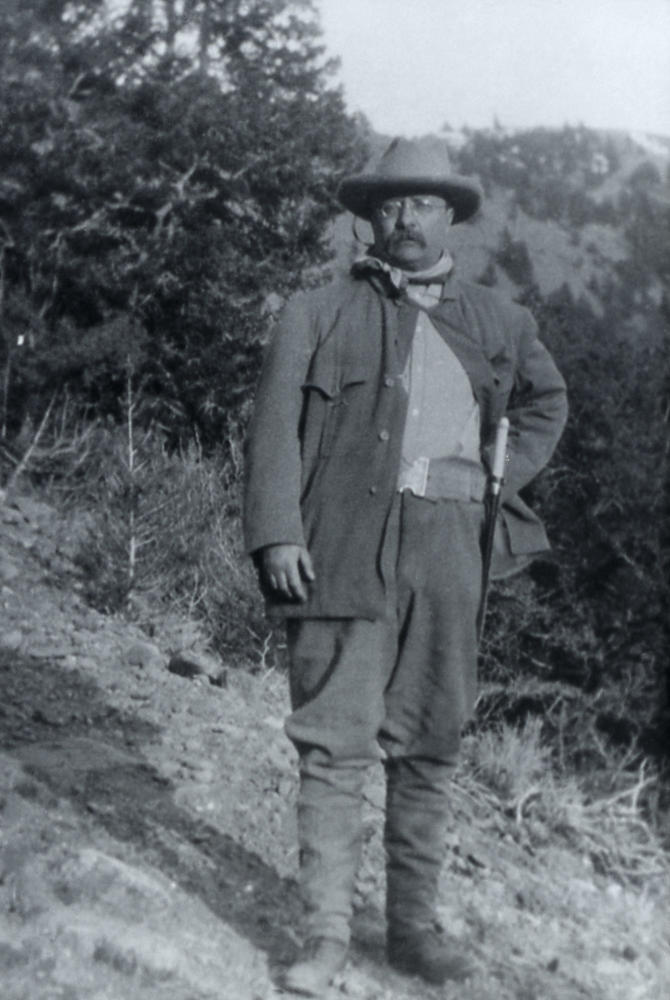

This image sent me rummaging through old newspapers. In 1908, President Theodore Roosevelt established Oregon’s Lake Malheur Reservation, dedicating about 100,000 acres of (allegedly) unclaimed government land to the preservation and breeding of native birds. American birds were in crisis. Milliners, in search of feathers for the fancy hats of the time, had nearly wiped out several species, including snowy egrets and roseate spoonbills. Headwear was such an important part of turn-of-the-century etiquette that there were instruction books on how to properly tip one’s hat, written at a level of detail reminiscent of the Japanese bowing tradition.

Lake Malheur Reservation specifically protected the formerly abundant great egret, which was a prime target for hatmakers. Earlier that year, conservationist William L. Finley had surveyed the area and found only two egrets during a full month of searching. Finley also interviewed a plume hunter who reported making as much as $500 per day (more than $12,000 in today’s dollars) selling the wading birds he shot. The same hunter boasted of plundering bird populations all the way to Mexico, exterminating entire egret colonies across the West. Finley’s report inspired Roosevelt to set the land aside for the bird’s benefit.

It worked for a while, but problems arose by 1920 (perhaps not surprisingly—malheur is French for “woe” or “misfortune”). As Oregon farmers drained water from the Silvies and Blitzen rivers, which feed into Lake Malheur, the lake was drying up and becoming alkaline. So a bunch of Oregonians came up with an idea: Why not just drain the lake and the surrounding wetlands entirely, then sell the land to farmers? To make the idea more palatable to the public, the proceeds from the sale would be earmarked for schools, hence the “babies before birds” motif in the advertisement above.

The ad’s complaint about mosquitoes seems trifling to a modern reader, but malaria was a major problem at the time. It was one of several imported diseases that together reduced Oregon’s indigenous population by 80 percent by the end of the Civil War in 1865. In 1920 the disease was still killing 58 out of 100,000 Americans annually—the approximate malarial death rate in modern-day Rwanda.

A political and legal battle ensued over Lake Malheur. The state gave voters the option to officially cede management of the area to the federal government. Angry Oregonians wrote letters to newspaper editors opposing the ballot measure, complaining that selling the land would bring value “far above any anticipated benefits that could possibly be derived from a bird reserve.” In a piece titled “Birds and Babies,” one writer noted that those pesky birds were stealing grain from local farmers. The ballot measure was defeated.

The U.S. government still wanted the land and fought a lengthy legal battle with Oregon. The state contended that the feds had more or less stolen the lake because Uncle Sam never really held title to the reserve in the first place. In 1935, the Supreme Court finally settled the issue, ruling that the land belonged to the federal government. The reserve was legitimate and the federal government had the authority to protect the wetlands from destruction. Take that, babies.

This story is, admittedly, a relic. But it’s an important one, because it encapsulates most of the arguments people continue to make against parkland. Opponents claim the land could be made more economically productive. They say wildlands are a detriment to society and do not help the average citizen. And they argue—somewhat bizarrely—that our children will one day thank us for not making parks.

Before establishing Yellowstone as a national park in 1872, for example, Congress demanded hard evidence that the land could not be used for farming, ranching, or housing. After its establishment, opponents still wanted to transfer management to a private company that would administer it in a less elitist and “imperial” manner. Before Glacier National Park was created in 1910, opponents cut the proposed area by two-thirds to allow mining and ranching. Similar concerns shrank the size of Grand Canyon National Park. (William Randolph Hearst also won a prohibition on structures that would impair the view from one of his houses.) Indeed, according to University of Montana historian H. Duane Hampton, two-thirds of existing national parks faced significant opposition.

The arguments continue. Last year, fishermen insisted that a proposed marine national monument was a waste of perfectly good tuna. Opponents of a massive Nevada national monument argued that President Obama was putting landscapes before our children’s safety (sound familiar?), because the Air Force needed the airspace for exercises.

No matter how good an idea is, there are always people who are against it. Pope Paul V declared Galileo’s ideas about the solar system heretical and told him to drop all that Copernican stuff. Of Darwin’s theory of evolution, William Jennings Bryan wrote that “no one has ever been able to trace one single species to another.” I’m sure there were people who warned against combining peanut butter and chocolate. I guess America’s best idea can’t escape the same fate, even after more than a century of making people (and their babies) happy.

This story originally appeared on Earthwire as “The People Who Opposed America’s Best Idea” and is re-published here under a Creative Commons license.