Way up in the mountains of Allegheny National Forest in northern Pennsylvania, you can dip your toe into a creek with no name. In minutes, the molecules of water sliding by your skin will be part of the Otter Branch. In hours, they’ll gain membership to Minister Creek.

Over the course of the following day, those same molecules will sing the battle hymn of the Allegheny River and then march alongside billions of their brethren as part of the Ohio River.

Eventually, the droplets from the no-name-creek will rage along the banks of the Mississippi and oxygenate the gills of a thresher shark in the Gulf of Mexico.

Politically speaking, developing a national network of river corridors may be easier to achieve than other large-scale conservation projects, such as migration corridors.

Water connects us—from fields and streams to mountains and beaches, and back again. Water molecules never lose their life-sustaining importance, but during their journey, they meander in and out of various levels of federal, state, tribal, and local protection.

That is why a team of scientists wants to create the first-ever riparian conservation network—a nationwide system of protected creeks, streams, and rivers the likes of which the world has never seen.

Riparian zones consist of rivers, floodplains, and wetlands, and Alexander Fremier, a Washington State University ecologist, thinks having these lush corridors connect protected lands to each other would be a bonanza for the environment. In a new paper outlining the idea in Biological Conservation, he and his co-authors explain how these links could improve water quality and help combat habitat loss and fragmentation.

Allowing more trees and shrubs to grow along banks staves off erosion, and banning livestock from grazing around rivers and streams could reduce sedimentation and nitrification (what happens when they, um, overfertilize a body of water). Less industrial pollution might also head downstream if there were tighter restrictions on mining and manufacturing near rivers.

Riparian corridors don’t just facilitate the flow of water from one region to the next; they also act as highways for wildlife. In one study of predators in California wine country, scientists found that coyotes and other small carnivores prefer to travel through forests, but when no trees are in sight, they take to the riverbanks. The research showed that waterways not only are important for the usual suspects of fish, ducks, muskrats, and the like, but are crucial routes for just about any animal looking to avoid humans and other dangers (think roads) on their journey.

OK, you may be thinking, this is all great, but connecting protected river corridors across the United States sounds like a daunting, if not impossible, undertaking—one that would require the cooperation of millions of private landowners and hundreds of federal, state, tribal, and local agencies. And you’d be right. But according to Fremier, this liquid network kind of, sort of exists already.

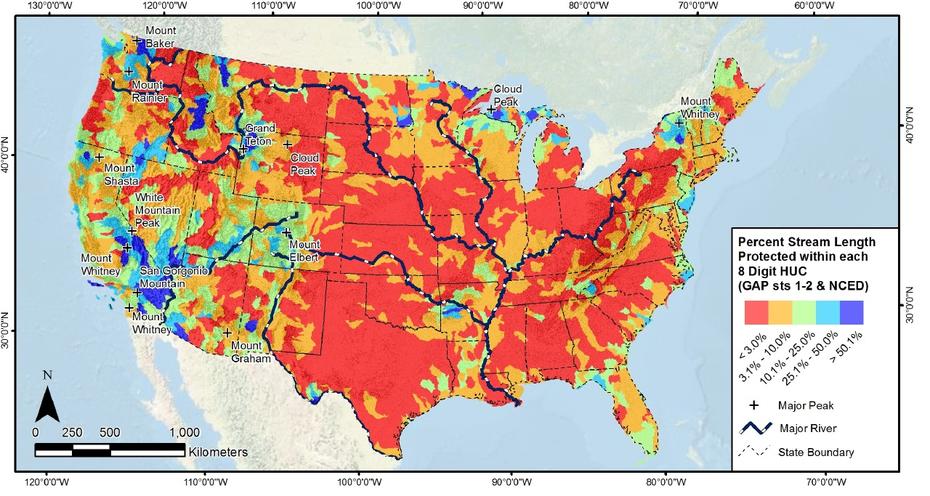

The federal government currently protects more than a million square miles of land. That’s about 12 percent of the country’s area, and much of it is riverine. Indeed, nearly a quarter of riparian zones have some safeguards in place already. What’s more, Fremier and company found that 95 percent of federally protected land is connected to at least one other protected area by a waterway. By conserving these streams that run between, we’d help bolster a patchwork of wilderness.

Things get even more interesting when you look at what private landowners are doing with their property. The researchers took a map of Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana and plotted all the places where people had created conservation easements—parcels of land that owners voluntarily set aside for conservation purposes in exchange for tax credits. What they discovered was that these parcels combine to form a de facto river corridor along the Mississippi, without any guidance from Uncle Sam, conservation organizations, or water quality experts.

Fremier admits that the region his team examined is part of the Mississippi floodplain. “For some people, the land is just flooding all the time,” he says, and so trying to farm it isn’t worthwhile. But this somewhat accidental corridor is another sign that a riparian conservation network is already under way. Just imagine what might happen if government agencies or conservationists further sweeten the deal.

Politically speaking, developing a national network of river corridors may be easier to achieve than other large-scale conservation projects, such as migration corridors. (Just look at all the different kinds of land pronghorn antelope pass through as they migrate from their winter range in Wyoming’s Green River Valley to their summer pastures in Grand Teton National Park.) That’s because the lines and boundaries of waterways are already drawn. A river or stream either exists in an area or it doesn’t. All you have to do is go with the flow—and protect it.

This story originally appeared on Earthwire as “A River Ran Through It” and is re-published here under a Creative Commons license.