The Trump administration has repeatedly vowed to help revitalize the nation’s nuclear power industry, which has struggled to compete with cheap renewables and natural gas in the United States since the fracking boom of the last decade. More than a year after the administration announced plans for a “complete review” to bolster the country’s nuclear-energy program both at home and abroad, it has yet to deliver a formal plan to do so.

But just last week, the U.S. inked a deal to build six nuclear reactors in India, which has plans to massively scale up its nuclear-power program to meet the country’s growing energy demands as it reduces emissions. Though only a small deal from a climate perspective, it’s a good sign for a U.S. industry that has struggled in recent years to maintain its dominance in international markets.

The U.S. has been a nuclear leader since the earliest days of the atomic age. In the post-World War II era, America’s national labs began churning out reactor designs. “There was a period of time when we were gung ho for nuclear power plants, especially after the 1970s energy crisis,” says Richard Nephew, a senior research scholar at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy. More than 100 nuclear power plants were built across the U.S., and in the second half of the 20th century, U.S. companies exported reactor designs, parts, and safety standards all over the world.

But a string of high-profile accidents at nuclear plants around the world soured public opinion of the technology in the U.S., and American developers all but gave up on building new plants in the States. While the new deal with India bodes well for U.S. developers’ ability to keeping selling their technology abroad, it does not change the state of the domestic industry: At least five U.S. plants have shut down since 2013, and another nine have announced plans to go offline in the next five years.

Right now, the major reason nuclear power plants are shutting down is economics. Utilities no longer want to buy into nuclear when natural gas and renewables like solar and wind are cheap. But climate change could soon change the equation.

“The U.S. fleet is, by just about any measure, still pretty much considered the top performing set of plants anywhere in the world,” says Michael Ford, an environmental fellow at Harvard University’s Center for the Environment. Today there are 98 nuclear reactors in operation across 30 states, with an average age of nearly 40.

Despite its advanced age, the average American plant has a generating capacity—a measure of the percentage of time a reactor is producing energy—of more than 90 percent. Plants abroad, meanwhile, have an average generating capacity of around 75 percent, according to Ford. “In terms of the ability to reliably generate electricity and safely generate electricity,” he says, “the U.S. fleet still sets the standard for performance.”

“The place that perhaps the U.S. is falling behind in is in the ability to build a new plant at schedule and at a low cost,” Ford says.

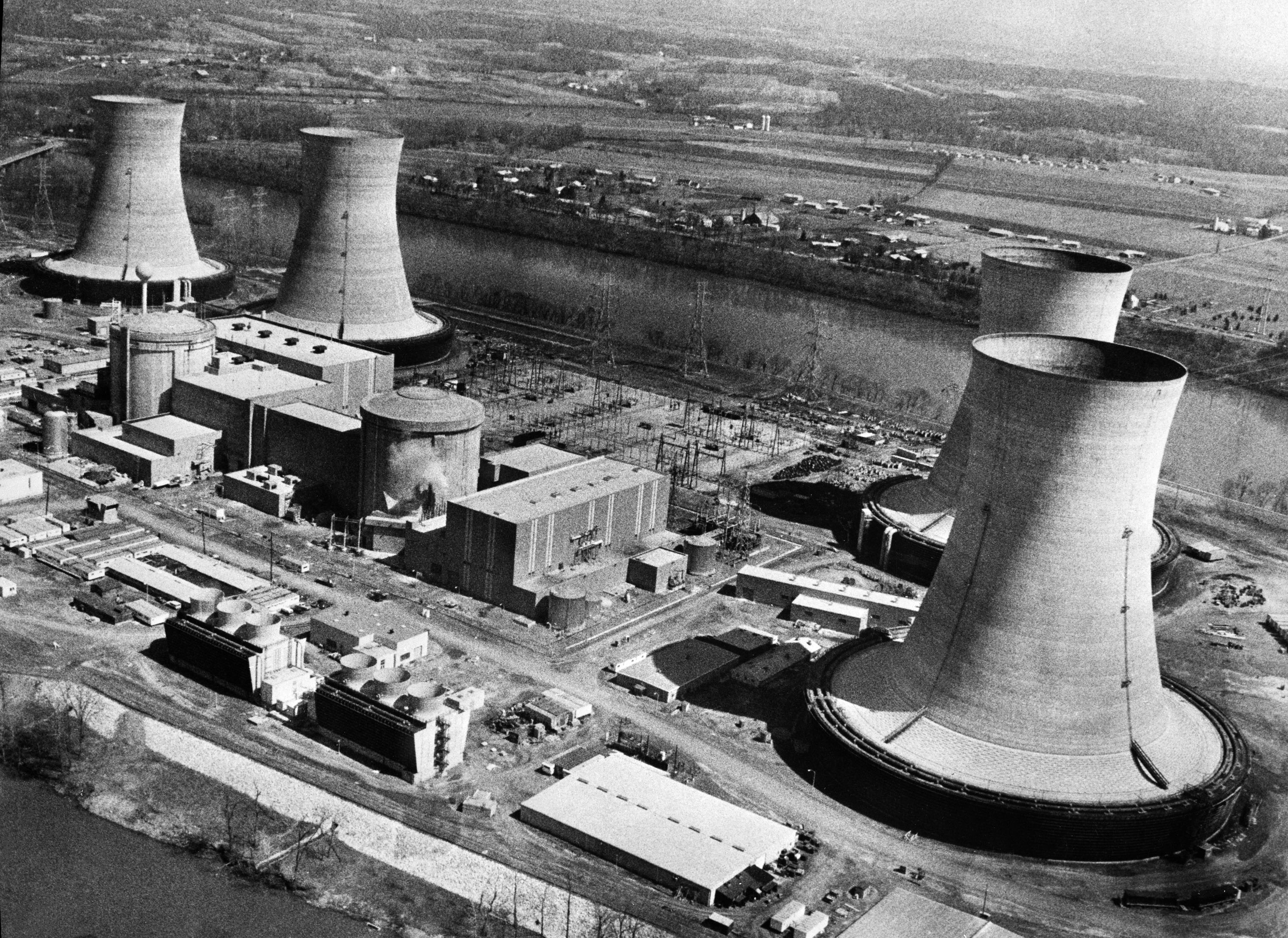

That can be traced back to 1979, when a partial meltdown occurred at a reactor at Pennsylvania’s Three Mile Island. The incident seriously damaged the plant’s reactor, but exposed the surrounding population to less excess radiation than they would have received from a single chest X-ray, according to the United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

Still, in the wake of the meltdown, public opinion turned against the technology, and the construction of new plants slowed in the U.S. and around the world. In the 10 years before the accident, construction began on an average of two dozen reactors around the world every year; afterwards, that number fell by more than half. Reactor designs and safety standards were updated—even for plants that were already under construction—leading both build times and construction costs to balloon. Other high-profile accidents at Chernobyl and Fukushima only solidified the technology’s controversial reputation in Western nations. While the U.S. has not gone so far as say, Germany, which is planning a complete phase out of nuclear power by 2022, its industry has remained stagnant for years.

(Photo: AFP/Getty Images)

Since 1996, only one new reactor has come online in the U.S., and the only new large-scale projects under construction are floundering. South Carolina spent $9 billion on the construction of two nuclear reactors before canceling the projects due to ballooning costs and construction delays. Two reactors under construction in Georgia appear destined for the same fate.

Meanwhile, South Korea, China, and Russia have managed to build new nuclear plants at cost and on schedule. According to Jacopo Buongiorno, a professor of nuclear science and engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the long hiatus from building new nuclear plants in the U.S. leaves American companies at a disadvantage compared to companies in countries like China, India, and South Korea, which have continued building new plants over the last few decades. Foreign companies still have experience managing the complex construction sites and can rely on an established supply chain and a qualified workforce, while U.S. companies “lost the know-how of how to build these plants,” he says.

That has made it difficult for the U.S. to maintain its influence and competitiveness internationally. In February, executives from U.S. nuclear developers—including long-time heavy weights like Westinghouse Electric Co., LLC, and General Electric Co., and start-ups such as NuScale Power, LLC, and TerraPower, LLC—met with President Donald Trump to ask for the White House’s help winning bids for international contracts. The executives said the international deals would lead to more manufacturing, construction, and engineering jobs for the U.S. economy, and noted that maintaining our position as the world’s top nuclear developer could be critical for national security.

“We were a major supplier of nuclear technology and nuclear expertise for a very, very long time,” says Nephew, “and as a result we got to help write the rules in a pretty significant way.” The U.S. has long pushed for strict rules for inspections, safety standards for plants, and non-proliferation clauses to prevent governments from using the technology to create nuclear weapons. It’s not yet clear if the U.S. will be able to maintain the level of influence it enjoyed as the leading nuclear developer.

According to Nephew, the first sign that the U.S.’s influence was declining came in the early 2000s, when President George Bush unsuccessfully lobbied the Nuclear Suppliers Group and the International Energy Agency to put more restrictive rules in place for nuclear commerce. “Now, some could argue that we were unsuccessful because we were aiming for home runs and total solutions, when singles and doubles would have been OK,” Nephew says. “But still, the upshot is, we were in a position to essentially write those rules in the ’60s and ’70s, but by the 2000s we were being emphatically told, ‘get lost,’ by even countries that nominally supported our policies.”

“I think it’s fair to say that if we don’t restore some of our commercial nuclear utility, we’re going to find ourselves complaining about the decisions of others, but not really being in a position to influence [them],” Nephew says.

Of course, there are other reasons why the U.S. may want to preserve its nuclear industry: chief among them, climate change. Despite a lack of federal leadership on climate, many states are still committed to decarbonizing their energy sectors over the next few decades and investing heavily in renewables like solar and wind. But renewables alone cannot currently meet all of our energy demands.

“The issue with renewables is that they’re intermittent,” Buongiorno says. “Everybody knows the sun doesn’t always shine, the wind doesn’t always blow, so when solar and wind do not generate electricity you either have blackouts, or to satisfy the demand you need to have a back-up, and that back-up now is natural gas.”

While natural gas has proved to be less carbon-intensive than coal, it’s still a significant source of emissions. Nuclear, on the other hand, generates 20 percent of the U.S.’s electricity needs without any carbon dioxide emissions at all. “Lets not forget that over half of our zero-carbon electricity in the U.S. comes from nuclear,” Buongiorno says, “so it’s by far right now, in the U.S. and in western Europe, the largest carbon-free electricity source.”

The nine U.S. plants slated to close over the next five years contributed about 90 billion kilowatt hours of low-carbon electricity to the grid in 2018—more than the total amount of solar energy generated in the U.S. that year.

Buongiorno and his colleagues looked at energy markets in the U.S., the United Kingdom, France, and China to find out how the power sector can decarbonize most efficiently and economically. In every case, a combination of solar, wind, and nuclear led to decarbonization at the lowest cost. New York, New Jersey, and Illinois have introduced subsidies to keep their nuclear power plants profitable and running, rather than trying to meet energy demands with renewables alone. But keeping America’s current fleet running is not enough to decarbonize the electricity sector.

“Ensuring that these plants continue to operate is simply a way to prevent us from taking steps back. We have this fleet of nuclear reactors, if we shut them down, our emissions will increase,” Buongiorno says. “If you want to deeply decarbonize, you need more solar, wind, and nuclear.”

In a 2018 report, Buongiorno and his colleagues pointed to a slew of construction management practices and new technologies that could help preserve the U.S.’s nuclear power industry going forward, including cheaper and safer reactor designs. NuScale, a nuclear developer out of Oregon, is working on a scaled-down version of the light water reactors that dominate the U.S. market. The water-cooled reactors are smaller, so they can be largely constructed in factories instead of on site, and the size makes it easier to design facilities with “passive” safety systems that rely on natural laws like gravity to power the core’s cooling system, which means that human operators don’t have to intervene if something goes wrong.

Another new reactor design with exciting implications for U.S. emissions is high temperature gas reactors. The helium-cooled reactors operate at much higher temperatures than water-cooled ones, which could be useful for industries beyond the power sector.

“Now you have a system that not only generates electricity, but also generates heat for other industrial processes, like making chemicals or materials such as synthetic fuels, nylon, and soda ash,” Buongiorno says. “It’s useful because a lot of the carbon emissions in our economy are not associated with the power sector, they’re associated with the manufacturing or industrial sectors.”

Gas-cooled reactors could even be a “game changer” for the transportation sector, which accounts for more than a quarter of U.S. emissions, because they can be used to create hydrogen-based fuels. (Electrifying cars and buses is one way to decarbonize transport, but sticking with combustion engines and switching to carbon-free, hydrogen fuel produced by nuclear plants is another.)

Even environmental groups that have long-been wary of nuclear energy are coming around to the technology as the world’s carbon budget shrinks and the dire consequences of climate change become ever more clear. “Nuclear power plants are controversial, for legitimate reasons,” Ken Kimmell, president of the Union of Concerned Scientists, wrote in a blog post last year. “But the IPCC report reminds us that we are running out of time and will have to make hard choices.”