Wilt Chamberlain’s 100-point game is the perfect record. It feels complete and final, an enduring round number. Set on a Friday night in March in 1962, in a game between Chamberlain’s Philadelphia Warriors and the New York Knicks, the record has stood, undisturbed, for 53 years. It has aged with grace and now feels unconquerable, but this is also an inherently subjective position.

What about Cal Ripken’s ironman streak of 2,632 consecutive games played? Or Cy Young’s 511 career wins? Or Wayne Gretzky needing only 39 games to score 50 goals? What about all of the other monumental achievements—the records that rise above a single sport and tower over them all? Is it possible to whittle them away until only one remains?*

In 1987, Bruce Golden and Edward Wasil attempted to find the greatest record in sports by applying the Analytic Hierarchy Process to 22 records. At the time, AHP was emerging as a leading formula in addressing complex, multi-criteria problems. Through AHP, bias could be reduced, if not eliminated, and equations solved with elements of both mathematics and psychology. When Golden and Wasil’s calculations were complete, at the top of the legendary list sat Chamberlain’s 100-point game.

Since then, AHP has evolved and become more refined, while new sports records have been set. When Golden and Wasil were conducting their original research, Nolan Ryan was still six years and two no-hitters away from retirement. Wayne Gretzky had yet to play a game for the Los Angeles Kings, or the St. Louis Blues, or the New York Rangers. Barry Bonds was just 23 years old and steroid-free—no one was betting that someday, in a single season, he’d send 73 balls on a flight-path to the moon.**

Of the 22 records compiled in Golden and Wasil’s 1987 study, 11 have been broken. In 2013, a team of researchers re-opened the file.

Liberatore admits that determining the best record in sports is a subjective process, but maintains that it can be driven by data, that the whimsy can be stripped away.

“We wanted to update it, define it a bit tighter, and focus it a little bit more,” says Matthew Liberatore, the study’s lead author and the director of the Center for Business Analytics at Villanova University.

Liberatore worked with three colleagues and they also recruited veteran sportswriter Jack McCallum—who joined Sports Illustrated in 1981 and has written eight books, including Dream Team, which chronicles the fabled 1992 Olympic Basketball team from the United States at the Barcelona Games—as an expert, someone to inform opinion and offer guidance.

McCallum also convinced Liberatore to add a second expert, his friend Thomas Hansen. Hansen doesn’t have a professional background in sports—he works for an investment firm—but Liberatore says his knowledge in the field was encyclopedic: “It was unbelievable. I’ve never seen anything like it.”

Liberatore admits that determining the best record in sports is a subjective process, but maintains that it can be driven by data, that the whimsy can be stripped away, and that the opinions of experts—in this case McCallum and Hansen—can improve the quality of the results.

So they settled on 65 recognized and reputable records limited to the four major American leagues—baseball, football, basketball, and hockey—and then identified criteria that could be applied to each record. The three major distinctions were: the duration of the record, incremental improvement, and then a catch-all category of “other.”

Under these three headings, the researchers created seven sub-criteria: the years the current record has stood, the years the previous record stood, the percentage the current record is better than the previous record, the percentage the current record is better than the next best performance, the era during which the record was set, how well known the record is, and then, finally, purity. Each of the criteria and sub-criteria were then weighted.

The era category considered rule changes, the rise of performance enhancing drugs, and the level of competition when the record was set. Purity refers to how much of the record was powered by one individual. In this case, a home run is a purer record than a run batted in. In basketball, scoring points is purer than assists.

The team also accounted for the fact that the leagues have all existed for different periods of time, allowing some records to outlive others. To solve this problem, they took the years the record has stood, divided it by the total number of years the record could have possibly stood, then took that percentage and multiplied it by 100. This gave them an adjusted record year. Then, to compare adjusted years across pairs of records, they squared the results (they determined this better reflected the impact of differences in adjusted length than a simple ratio).

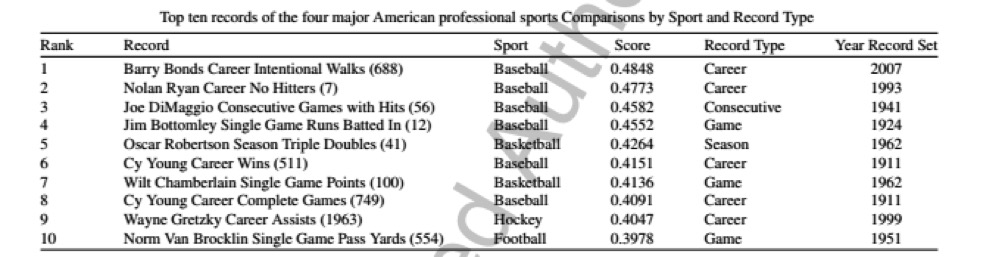

When all of the calculations had been applied, Barry Bonds’ record for 688 intentional walks was at the top of the list. The last ranked record also belonged to Bonds, for his 73 home run season.

“We were very surprised by the results,” Liberatore says. “It wasn’t at all what I expected.” Despite getting a low era score, for occurring during a period of rampant steroid use, Bonds’ record for intentional walks was catapulted forward because it obliterates the next closest, which belongs to Hank Aaron (293). Ryan was next on the list, for tallying seven career no-hitters, and only 1.5 percent behind Bonds overall.

“What that says is if certain weights or certain factors change, even a very small percentage, that could switch over,” Liberatore says. “Ryan could be number one.” Even Joe DiMaggio, who came in third for recording a hit in 56 consecutive games, could move up to the top.

“Small changes in some of the criteria flip things around,” Liberatore says. “It’s an unbiased way of coming up with the results, but if you adjust the weights or drop a factor, it could affect it.”

This time, Chamberlain’s 100-point game fell to seventh overall, partly due to Kobe Bryant’s 81-point game in 2006. A drop that, objectivity aside, even stings for Liberatore.

“I hate seeing Barry Bonds’ record at number one, personally,” he says. “I’m like you, my favorite record of all time is Wilt’s 100-point game, but 100 on a ratio is not that much better than 81, the next best record. If Bryant didn’t have that game, that might have been enough to change it.”

Liberatore says the team, McCallum and Hansen included, are comfortable with the results. They took on the exercise to try and gain some clarity, and they feel they achieved that. They’re also aware the conversation isn’t over. The whimsy remains.

“This doesn’t end the issue of what the best record is in American professional sports,” Liberatore says. “It’s just a way—the least unbiased way possible—to make an assessment of sports. It’s an interesting exercise to see how it falls out.”

The Sports Lens is a running series exploring the intersection of sports and culture.

*Update — October 29, 2015: Cy Young ended his career with 511 wins, still the record for most career wins by a pitcher.

**Update — October 29, 2015: Barry Bonds’s record is for 73 home runs in a single season.