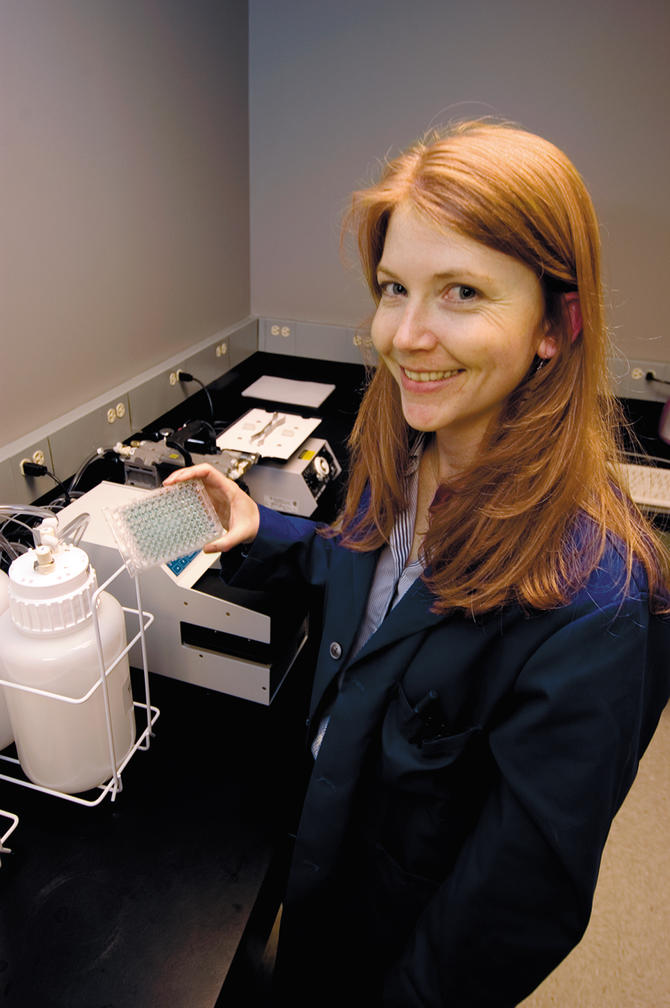

There’s a Dr. Poop at work in Chicago’s Lincoln Park Zoo. Her real name is Rachel Santymire, and she’s the director of the Davee Center for Epidemiology and Endocrinology. She and her staff test stool and pull hair, all in the name of animal health and conservation.

Santymire is not only the zoo’s poop expert but also the resident matchmaker. (Turns out collecting excrement and sparking love connections go hand-in-hand.) Hormones in feces and fur can tell us if an animal’s stressed or ready to mate. From the samples, Santymire’s lab can see if an animal has high levels of the stress hormone cortisol (maybe due to a new exhibit mate or nearby construction noise or too many punk-nose kids tapping on the glass). And when she sees that the sex hormones estrogen and progesterone or testosterone are high, she lets the zookeepers know to turn up the Barry White, so to speak. By learning these chemical signposts for romance, Santymire is helping give endangered species populations, like rhinos and black-footed ferrets, a boost in both captivity and in the wild.

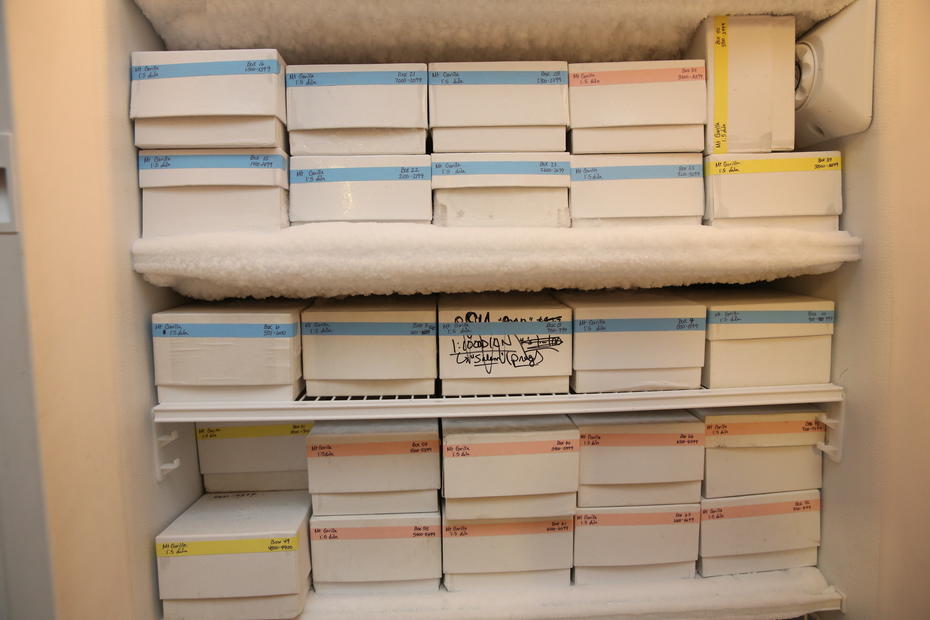

Santymire’s self-described “poop hoarding” began about a decade ago and has since expanded to fill 10 freezers’ worth. Feces just provide so much great intel, she says. “It’s a unique point in time that you can’t go back to, so I tend to just buy more freezers. That’s been my strategy.”

After a zookeeper shovels the poop into a Ziplock bag, Santymire freezes it, and then someone from the zoo’s epidemiology and endocrinology department takes it to the lab. There, technicians scoop it out, weigh it, add ethanol, and then shake. The alcohol draws out the hormones, and the techs then run the liquid through an assay, a test to determine their concentrations. (They use the same process, sans the freezer, for pulverized hair.)

With enough data, eventually a baseline for the species emerges—a rare thing since we just don’t know that much about different species’ chemical journeys. Now Santymire can get snapshots of the animals’ hormonal cycles and what might trigger them over time.

Poop at the zoo, however, poses challenges, especially when all the animals relieve themselves in the same enclosure. That’s why Santymire and her team put food coloring, non-toxic glitter, or birdseed in individual treats. For instance, a wild dog may get a sparkly meatball, so when the keepers see a glinting pile, they’ll know who it came from.

Wild settings bring even more obstacles because it’s hard to know when and where an animal is going to let loose. When Santymire and a team went to Tanzania’s Gombe Stream National Park to study black rhinos, they put digital cameras in dung piles to take a date-stamped action shot of each pie maker.

For furrier subjects, the process can be less smelly. Stealing the idea from forensic science, Santymire tests hair for hormones. In the case of black-footed ferrets, biologists have been trapping the furballs and then pulling out a plug or two. Santymire is currently comparing hair from wild black-footed ferrets to those in captivity in order to document any difference in stress levels between the populations.

Her next quarry will be the steamy droppings of the endangered snow leopard. As few as 7,000 of these big cats are left in the mountains of Central Asia, but the 150 in United States zoos could help boost their wild cousins’ numbers. In an effort to get more captive leopards pregnant, the Association of Zoos and Aquariums just gave a grant to Dr. Poop to transform into Dr. Ruth.

This post originally appeared on Earthwire as “Fecal Attraction” and is re-published here under a Creative Commons license.