One of the major contributions of political scientist Benedict Anderson is the idea of an “imagined community”: a large group of people connected not through interaction, but by the idea that they are part of a meaningful group. In his book on the idea, he wrote:

It is imagined because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet … it is imagined as a community, because, regardless of the actual inequality and exploitation that may prevail in each, the nation is always conceived as a deep, horizontal comradeship. I suppose the idea might apply as well to religions.

Last week was a special week for American Catholics. The Pope’s visit to the United States was energizing, arguably intensifying the connection Catholics feel to their religion and, by extension, each other. But what, really, do Catholics have in common?

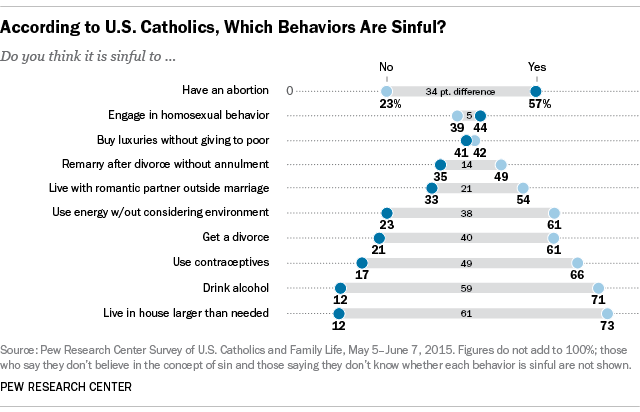

I don’t know, but agreement on what is sinful is not one of them. A Pew Research Center survey of Catholics reveals, instead, quite a lot of disagreement. Some Catholics don’t believe in the concept of sin at all and the remaining don’t always agree on what is sinful.

According to the results of the survey, for example, there is considerable disagreement as to whether abortion, homosexual behavior, hoarding wealth, divorce, unmarried co-habitation, and harming the environment are sinful. Moreover, plenty do not ascribe to some aspects of Catholic doctrine: Only 17 percent of Catholics, for example, think that using contraception is sinful.

So, what does it mean to be Catholic?

Anderson might argue that they are simply an imagined community: a group of strangers with widely divergent views and life circumstances who feel the same despite all the reasons to feel different.

This post originally appeared on Sociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner site, as “What, If Anything, Do Catholics Have in Common?”