Not all access is created equal. This is the truth we need to hold self-evident when we create tools for civic (that is, democratic) participation.

Over the last decade, digital activists like myself have been working to make civic information more accessible in a literal way: creating open data and civic technologies in order to increase the amount, “findability,” and usability of government information. Occasionally, our work goes deeper, looking at the structural barriers to this access that class, capital, and the digital divide create. But even as our conversation begins to include more nuance about digital literacy (where we understand “access” as more than the ability to touch a thing, but rather as the ability to conceptually and equitably use that thing), the one barrier we commonly ignore—the one barrier that remains whether we’re dealing with paper forms or digital—is language.

With VoterVOX, 18 Million Rising hopes to change that.

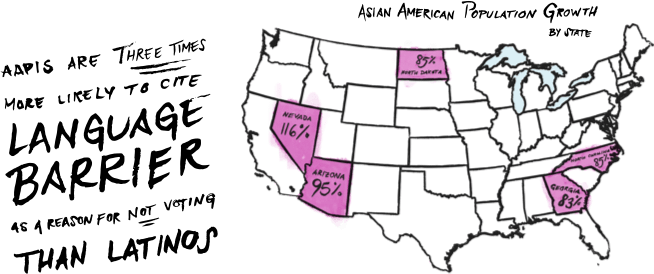

18 Million Rising is an online advocacy group founded in 2012 to support the civic engagement of the approximately 18 million Asian and Pacific Islanders in the United States. Despite representing six percent of the U.S. population and growing faster than any other demographic, only 55 percent of Asian-American citizens of voting age are registered to vote—the lowest rate of all races.

In a recent Civicist piece, 18 Million Rising’s chief technology officer, Cayden Mak, noted that it’s all too easy to write off this lack of registration as “voter apathy” rather than examining the systematic failures of our civic infrastructure that prohibit the engagement of this population. Take, for example, the lack of voting information made available in non-English languages.

“There might be hundreds of languages spoken in our country,” Mak wrote, “but they aren’t spoken by our government.”

According to the 2009 Census, 80 percent of Americans speak English. But English is our national language only in an informal sense. Although our Constitution is written in English, although 27 states within the U.S. (and all our inhabited territories) have designated English as their official language, and although there’s plenty of precedence worldwide for official languages, the U.S. has no official language—and therefore no mandate to constrict the availability and equitable accessibility of civic material on linguistic grounds.

In fact, we have the opposite mandate. In 1965, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act into law to remove racial and linguistic barriers to the ballot box. In addition to tackling a number of measures related to literacy, the Act also mandated that translated voting ballots and materials be available to language minority populations—but only for those districts where this population is “significant” in its Census-determined density. When evaluated in terms of literal access, this provision goes a long way toward opening up the electoral system. (More access in more languages for more people!) But if we examine it in terms of equitable access—access that is made available fairly, with attention to pre-existing differences in privilege and experience—this provision falls short. Requiring that translation be available only when those who need it live in “significant” numbers institutionalizes a barrier to civic access for those who need it most: the small, present, and growing numbers of U.S. citizens, living all across the country in communities of varying size and composition, designated with “Limited English Proficiency.”

The American Community Survey estimates that the number of Asian or Pacific Islander Americans (AAPI) who speak English less than fluently is nearly seven million people. This population is linguistically and ethnically diverse and often speaks non-English languages at home. Even when bilingual voter registration and ballot services are offered to these Americans, there is a notable lack of consistency and quality in support, as evidenced in research from the Asian American Justice Center, Asian and Pacific Islander American Vote, and National Asian American Survey.

With or without English proficiency, with or without the boundaries of an official national tongue, with or without “significant” density, these Americans deserve the right to embody their citizenship and fully participate in our democracy.

But even if we accept this—that equitable civic participation must be founded on equitable access to information, and that the latter means more than just literally having access to info in the language that you need, the question remains: What does equitable access look like?

“Language access is about designing systems that include people in every step of the process,” wrote 18MR’s Mak, citing research from public policy shop Demos, as well as work from activist Tanzila Ahmed that highlights that, although language is a key barrier to AAPI participation, translation is complicated, and connected to many other information asymmetries that discourage, prevent, or otherwise disenfranchise these potential voters.

“Creating access [to translation] isn’t a matter of delivering information from a central source to LEP voters,” Mak continued, “but a matter of helping communities organize themselves.” This is the underlying strategy for VoterVOX: activate existing community capacity and resources which already support Limited English Proficient citizens and integrate translation of civic information into this structure.

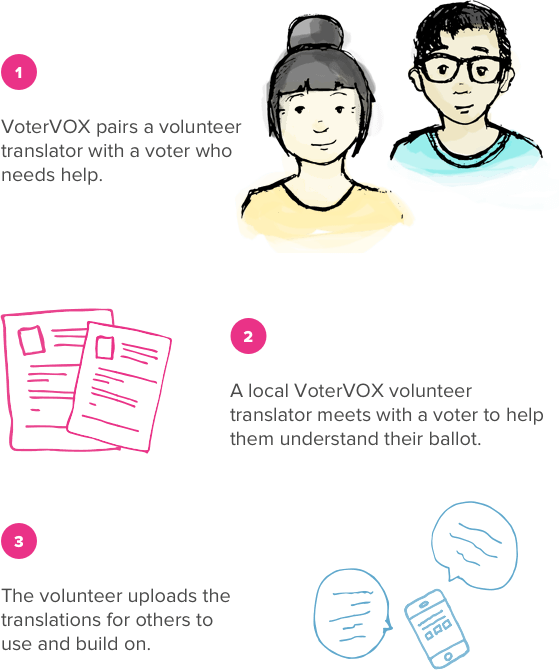

Here’s how it works: VoterVOX networks local community partners to match multilingual Asian or Pacific Islander Americans with limited English speakers and provide in-person, one-to-one translation of voting materials and jargon. After the volunteer and the voter-in-need meet and talk, the voter submits their mail-in ballot on their own, while the volunteer uploads their translation and experience to the VoterVOX app as an aid to other volunteers.

Or, rather, that’s how it will work. Currently, VoterVOX is still under development. “The spark for #VoterVOX actually came from @beingbrina [Sabrina Hersi Issa].” Mak tweeted during a Twitter chat I took part. Hersi Issa runs Be Bold Media, a tech and media agency focused on human rights, but the particular inspiration Mak referenced was a personal experience. In 2012, Hersi Issa provided one-to-one translation to help her grandmother vote in her first election as a U.S. citizen.

“In the past,” Hersi Issa tweeted, “I’ve built tech to expand access and services to healthcare and humanitarian relief. And in that context, it was vital and necessary to use tech to reimagine systems not designed for marginalized/underrepresented. But until I lived the experience translating at the polls, I did not see the terrible UX [user experience] of our democracy.”

Qualitative experiences of discomfort and disenfranchisement can be as valid a call to action as their quantitative measure. We can cite statistics until our faces turn blue (for example, that, according to the Census Current Population Survey, Asian or Pacific Islander Americans are three times more likely than Latin populations to cite language barriers as a reason for not voting, or that, according to a 2012 exit poll from the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund, nearly one in four Asian Americans prefer to vote with help from an interpreter or translated materials), but it’s lived experiences like Hersi Issa’s and countless others, recorded and unrecorded, that demonstrate the true difference between projected and real access to democracy. Investment in these experiences—and in solutions that respond to their call to prioritize context, personal experience, and existing social realities—have been shown to make a difference.

Earlier this year, I conducted a series of studies with the Smart Chicago Collaborative that investigated this approach to creating civic technology: how, in other words, people who want to address a social problem with a technological solution do so with, not for the community they hope to serve. My methodology involved both independent review as well as in-depth self-reporting from 17 projects. The technologies ranged from mobile apps to radio towers, QR codes to hotlines, but the modes employed were largely the same. Chief among them: invest in relationship-building, partner with hyperlocal groups with intersecting interests, lead from common physical and cultural spaces, build the tool that fits (not the app you want), and be a community participant. Not just a participant in any community. A participant in the community you are trying to serve.

VoterVOX, like 18 Million Rising itself, is grounded in Asian-American and Pacific Islander American experiences and realities. Its emphasis on in-person, one-to-one translation might go against the trends of “scalable universality” present in civic tech writ large today (and crowdsourced translation in particular), but VoterVOX’s focus on the individual and the communal is a strategic choice—one that, by the measures of its community tech predecessors, implies a high chance of success over the long-run of its implementation. Rather than complicating the process of translation with layers of technology that could ultimately end up further excluding their target population (who may not, for example, share a universal level of digital access and literacy), VoterVOX follows a traditional community organizing method based on meeting people where they are.

And ultimately, that’s what all this is about. When our democracy fails to make equitable pathways for participation and inclusion, we as individuals and communities must carve those pathways ourselves. “Meeting people where they are” means just that: physically going to locations that the people you want to serve frequent (libraries, social clubs), working at whatever degree of educational or technological skill the people you want to serve posses, and collaborating with the social structures these individuals and communities already rely on (families, community groups, senior centers).

If realized, VoterVOX won’t just be the latest in civic technology, but a manifestation of democracy. The equitable kind. The actually accessible kind. The only kind of civic tech, or democratic work, worth investing in.

This post originally appeared in New America’s digital magazine, The Weekly Wonk, a Pacific Standard partner site. Sign up to get The Weekly Wonk delivered to your inbox, and follow @NewAmerica on Twitter.