Martin heard the French-speaking policemen before he could see them. It was the first day of September in 2017 and he had been picking plantains on the far end of his family’s cocoa farm in Mamfe, Cameroon, when a commotion broke out. He walked over to the area where local farmers hired for the new season were working, only to find them and his father surrounded by a group of armed military men dressed in fatigues. “Turn around and run away!” Martin heard his father shout as a bullet cut through the air around him.

That night and for the following month, Martin, whose last name is omitted for his safety, his mother, and his four younger siblings sought refuge in a wooded area behind the property. For many Anglophone families like Martin’s, the mosquito-infested bushes had become hideouts to avoid the increasingly common police round-ups. They had even developed a communication system between the farms: Whenever a neighbor rang a bell, everyone else knew to run to the bushes.

The northwest and southwest regions of Cameroon have been in turmoil ever since late 2016, when the Francophone central government violently suppressed a series of peaceful protests against the marginalization of the English-speaking minority—about 20 percent of the overall population. In response to the crackdown, separatist groups gained traction, prompting security forces to raid villages like Martin’s and targeting those suspected of supporting the cause.

Martin’s involvement with the separatist movement had started a few months before the attack on his family’s farm. At the time, he had taken it upon himself to teach young children in his village the national anthem for a self-declared state called Ambazonia. That was enough, he says, for the police to threaten to kill him. Then, on October 1st, Martin joined thousands of demonstrators across the Anglophone regions to celebrate their symbolic independence. Gathering in a public square, they waved the white- and blue-striped flag and held tree branches as a sign of peace. Standing close to the front row, Martin watched as security forces shot the leader of the march and used tear gas to disperse the crowd. When a policeman hit him in the ribs, Martin was left coughing up blood and unable to walk because of the pain.

At least 20 people were reportedly killed during the protests that fall. Martin knew then that staying in Cameroon would be a death sentence.

Martin fled to seek asylum in the United States a few days after the march. Since he left Cameroon, the Anglophone crisis has escalated into a full-fledged armed conflict between the security forces and separatist groups, plunging the country into near-civil war.

According to Amnesty International, at least 400 civilians had been killed as of last year, and humanitarian groups continue to accuse the government of committing extrajudicial executions, burning down villages, and torturing and arresting people without charges. Armed separatist groups have reportedly killed at least 44 security forces members between September of 2017 and May of 2018, and have perpetrated attacks on teachers and students to enforce school boycotts in protest against the Francophone government.

As a result, as many as 437,000 people are currently internally displaced, and thousands of others are living in refugee camps in Nigeria. Still, despite the staggering figures, the humanitarian calamity “has been met with deafening silence” by the international community, according to a report from the Norwegian Refugee Council, which ranked it as the most neglected displacement crisis in the world.

As the conditions pushing the Anglophone population to flee continue to deteriorate and routes to Europe prove to be prohibitively dangerous, more and more Cameroonians are risking a long journey to safety in the U.S. According to data from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the number of Cameroonians applying for asylum in the U.S. more than doubled—from 821 to 1,840—between 2015 and 2017, and now Cameroonians are among the top 10 nationalities arriving at the border to ask for protection. But with the Trump administration taking several steps to limit asylum, Cameroonians are facing increasing likelihood of being returned to the same threats they hoped to escape in the first place.

For those sent back, Martin says, “It’s like living in hell there. People are being killed like flies.”

After leaving behind a war-torn country, asylum seekers from Cameroon often head to Ecuador, where they are visa-exempt. But without Spanish language skills and fearing racial discrimination, many like Martin decide to continue north. For Martin, the 15,000-mile journey meant spending $3,000 on plane tickets to Liberia, Ghana, Spain, and then to Ecuador, where he hopped on buses to Colombia and took boats to the notorious Darien Gap, a 60-mile remote stretch of rainforest on the border with Panama.

African migrants often report being robbed, beaten, and extorted while crossing South and Central America. Martin says he was attacked in the jungle by six men armed with guns and machetes who stole his food and clothes. He had to walk for days under heavy rain, drinking water from streams, and sleeping under rocks and trees.

Other asylum seekers from Cameroon describe seeing abandoned bodies along the way. “That journey is another war of its own. But you just have to continue because if you go back, you’re dead already,” says Tony, who left Cameroon in 2017 and was granted asylum in the U.S. after being targeted for taking part in the protests and for his father’s affiliation with the Southern Cameroons National Council, a group calling for secession.

Those who make it past the jungle in Panama find their way to a refugee camp in Costa Rica, and from there head to Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, and Mexico, until finally arriving at the border with the U.S. But a growing number of Cameroonians are finding themselves stuck in dangerous Mexican towns. Since 2018, U.S. Customs and Border Protection has been implementing a metering system to allow fewer migrants to cross through ports of entry every day, forcing people to wait for months to make their asylum claims. And for those arriving today, seeking protection in the U.S. might not even be an option. Under the safe third country rule agreement signed with Guatemala in July, anyone who passes through another country where she could have requested protection will no longer qualify for asylum in the U.S.

(Photo: AFP/Getty Images)

By the time Martin reached the San Ysidro port of entry in San Diego, California, and presented himself to immigration authorities to ask for asylum, he had been traveling for four months. Still in pain from the police beating back in Cameroon, Martin was taken to a hospital, where he was diagnosed with a broken rib and a blood clot in his stomach, before being taken into custody of CBP. While still feeling the effects of pain medication, Martin had his credible fear interview with an asylum officer—a crucial first step in the process to determine whether a person has the right to a hearing before an immigration judge to avoid immediate deportation—who found him to have a reasonable fear of returning to his home country.

From the temporary holding facility at the border, Martin was transferred to a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention center in Aurora, Colorado. In his application for asylum, Martin wrote that he was afraid of being persecuted for his involvement in protests in support of independence for the Anglophone minority. “Sir, if I returned to my country of Cameroon,” he stated, “just know that I will be a dead man.”

After a few months in detention, Martin was struggling with severe depression. He had recurring flashbacks, headaches, and panic attacks. “Life is unbearable,” Martin wrote as part of a memoir he started while in ICE custody. “It is truly a prison, except the health care is worse. The food is unrecognizable, and on many days, inedible.”

At the time, Darren Straus, a volunteer with the non-profit organization Casa de Paz, paid visits to Martin and said he was extremely distraught. “He didn’t know what was happening to him,” Straus recalls.

Feeling confident about the strength of his case, Martin requested for his immigration hearing to be moved to an earlier date. Like the overwhelming majority of detained immigrants, Martin didn’t have access to an attorney when he went before immigration judge Nina Carbone in May of 2018. A couple of days later, her decision came: She found Martin not credible and denied him asylum. In her written decision, Carbone noted that Martin was “visibly upset and tearful during his testimony.” The judge pointed to some inconsistencies between his testimony and the information he gave during the credible fear interview, including the exact date he left Cameroon. Martin also forgot to mention having been harmed by the police during the October protest. The transcripts show multiple indications of “indiscernible” parts where the court reporter couldn’t understand Martin’s words.

Martin appealed the judge’s decision and, while it was pending, he was released on parole to live with his sponsors, Straus and his wife Sarah, in Highlands Ranch, Colorado. The couple was used to visiting detainees at that point, but something about Martin’s story and the fact that he didn’t know anyone in the U.S. compelled them to welcome him into their home. “We never felt there was an option,” Straus says.

They also found an immigration attorney to help Martin with his case. After the Board of Immigration Appeals affirmed the immigration judge’s decision to order Martin deported last October, Denver-based lawyer Mark Barr filed a motion to re-open the case and introduce new evidence that could reverse the negative outcome, including a mental-health evaluation determining that Martin has signs of post-traumatic stress disorder.

“The judge didn’t believe Martin’s story because he was confused and scared and breaking down on the stand,” says Barr, who describes the recording of the hearing with the immigration judge as heartbreaking. “Not only is he crying over what he’s afraid of, but because he doesn’t know if his whole family has been killed or not.”

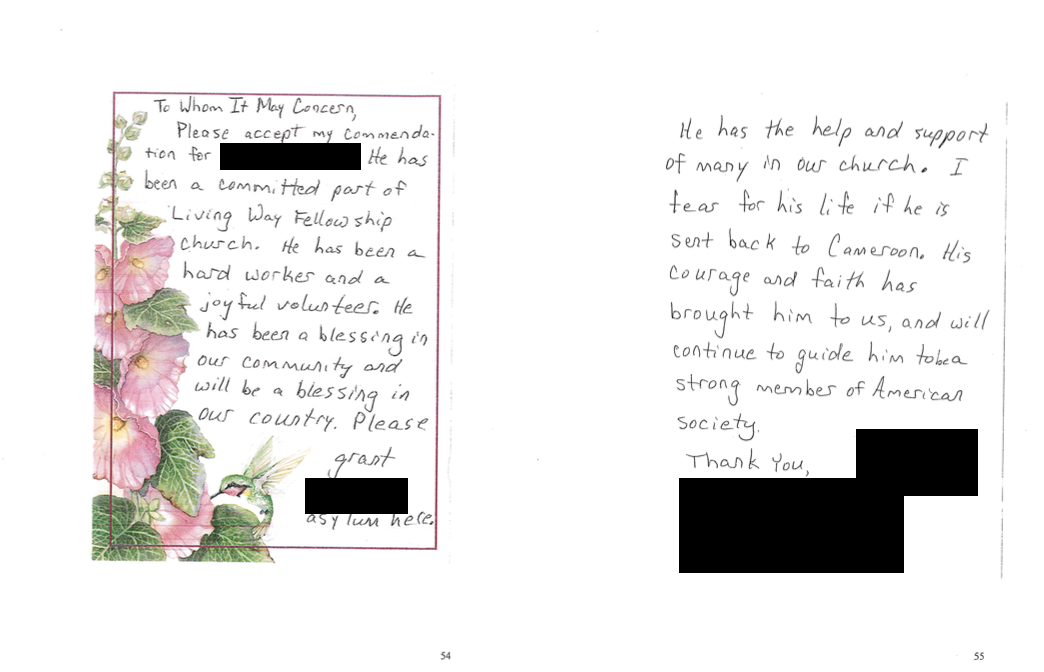

For a while, as he waited for his appeal case, Martin was able to create a life for himself in Colorado. He started attending a men’s Bible study on Wednesday evenings at the Living Way Fellowship Church, joined a soccer team, and often helped neighbors by walking their dogs or raking leaves. Much to the surprise of Straus, who describes the community as “white, conservative, and Christian,” people have embraced Martin in return.

An ongoing petition asking ICE to stop his deportation now has more than 5,000 signatures, and a crowdfunding campaign has raised more than $8,000 to help with his legal fees. In two-dozen letters gathered by Martin’s attorney to support his case, members of the community describe him as having a diligent character and being reliable, hard-working, and, above all, trustworthy. One person wrote: “I do not expect the U.S. Government to guarantee his safety as a resident of our country, but I do expect the government to prevent his physical harm in a foreign one.”

As more Cameroonians arrive at the border to request asylum in the U.S., the number of cases approved has also gone up, from 92 in 2015 to 218 in 2017. But so has the number of Cameroonians being sent back: For the fiscal years 2017 and 2018 combined, 130 nationals of Cameroon were deported, compared to only 29 in 2016.

For many deportees, returning to Cameroon means immediate detention and, in some instances, violence. When Agbor, an Anglophone teacher in his hometown of Kumba and a vocal supporter of the separatist cause, arrived in Cameroon from the U.S. last October, he was arrested for questioning by the police at the airport.

“They knew I was coming,” he says. Agbor, whose last name is also omitted for his safety, was only released after his family paid the police commissioner a sum of $1,500. “The majority of my colleague teachers in the fight for secession went to jail and their families don’t even know their whereabouts,” Agbor says. “I knew that being in prison would be the gateway to my death.”

While the U.S. has acknowledged the bleak conditions in Cameroon in Department of State country reports and advises American citizens against traveling to the Anglophone regions due to armed conflict, crime, and kidnapping, it has done little to address the crisis. According to Alexandra Lamarche, an advocate with Refugees International who traveled to Cameroon last March to report on the displaced population, the U.S. has only provided $300,000 in humanitarian aid to the southwest and northwest regions out of a total of $18.4 million designated to Cameroon in 2019. Meanwhile, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs estimates the needs in the Anglophone areas at $93.5 million.

“The population is increasing every day,” says Agbor, who is working with a non-profit organization to provide assistance to the internally displaced, mostly families whose houses have been burned down and children who lost their parents to the armed conflict.

“It’s a genocidal war,” he says.

Recently, Martin learned through a childhood friend that his father has been released from jail after two years. But his family continues to live in the bushes: Their house was burned to the ground by government security forces, and one of Martin’s brothers was shot in the leg after the police searched his phone and found text messages exchanged with Martin’s lawyer. According to the friend’s accounts, the government forces have put up flyers with a picture of Martin at the airports in Douala and Yaoundé, Cameroon’s two biggest cities. “I know that his life will be in danger if he returns,” Martin’s friend wrote in a statement to assist his asylum case. “I know because my own life is in danger.”

Last April, Martin was detained again during one of his check-in appointments with ICE and has since been denied parole. He could be deported any day now, even with the pending motion to re-open his case. If the motion is denied, he could still appeal to a higher federal court, the Tenth Circuit, but the standards are exceptionally high. “If he is deported and he wins, the government would have to arrange for him to come back to the U.S,” Barr says. “But that of course would all be rendered moot if he was sent back to Cameroon and killed.”

In detention, Martin reads the Bible every day but he still can’t make sense of his situation. During a recent phone call, he sounded agitated and desperate. “He never doubted the merits of his case,” Straus says. “But I think he’s getting toward the end of his rope by being locked up.”

If Martin is released and allowed to stay in the U.S., he says he would go back to living with Darren and Sarah Straus. He would also work to open a chocolate shop. But above all, Martin is hoping to be free so that he can help his friends and family back home.

“I’m just hoping it will be done,” Martin says.