Every five years, the country’s most powerful group of nutritionists convenes in the capitol to decide what Americans should be eating. A committee of 20 health and nutrition experts, announced last month, is tasked with revising and reissuing the Dietary Guidelines for Americans for 2020. The recommendations determine what goes into school lunches and public benefit programs, as well as what goes on the food pyramid—now known as MyPlate—in health classes everywhere.

Few Americans actually follow these guidelines, and many nutritionists have questioned their effectiveness. But that doesn’t mean they don’t matter: Between the military; the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children; and the National School Lunch Program, millions of people’s diets are shaped by the input of one committee.

Some scientists, however, would like the guidelines to reach even further—addressing not only food’s nutritional value, but the impact that its production has on the environment. The inclusion of sustainability, which threw last round’s committee into controversy, was ultimately scuttled by pushback from the meat industry. Now, it could be passed over once more: After the last attempt failed, Politico reports that “no one in Washington expects the 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans to venture into sustainability this round.”

How did debate over a science-based document get so heated? Even before the sustainability debate, the guidelines were somewhat controversial. United States Department of Agriculture officials consider the food pyramid the “cornerstone of federal nutrition policy;” others have called it a “lightning rod for praise and for criticism.”

From ‘Patriotic Propaganda’ to Independent Review

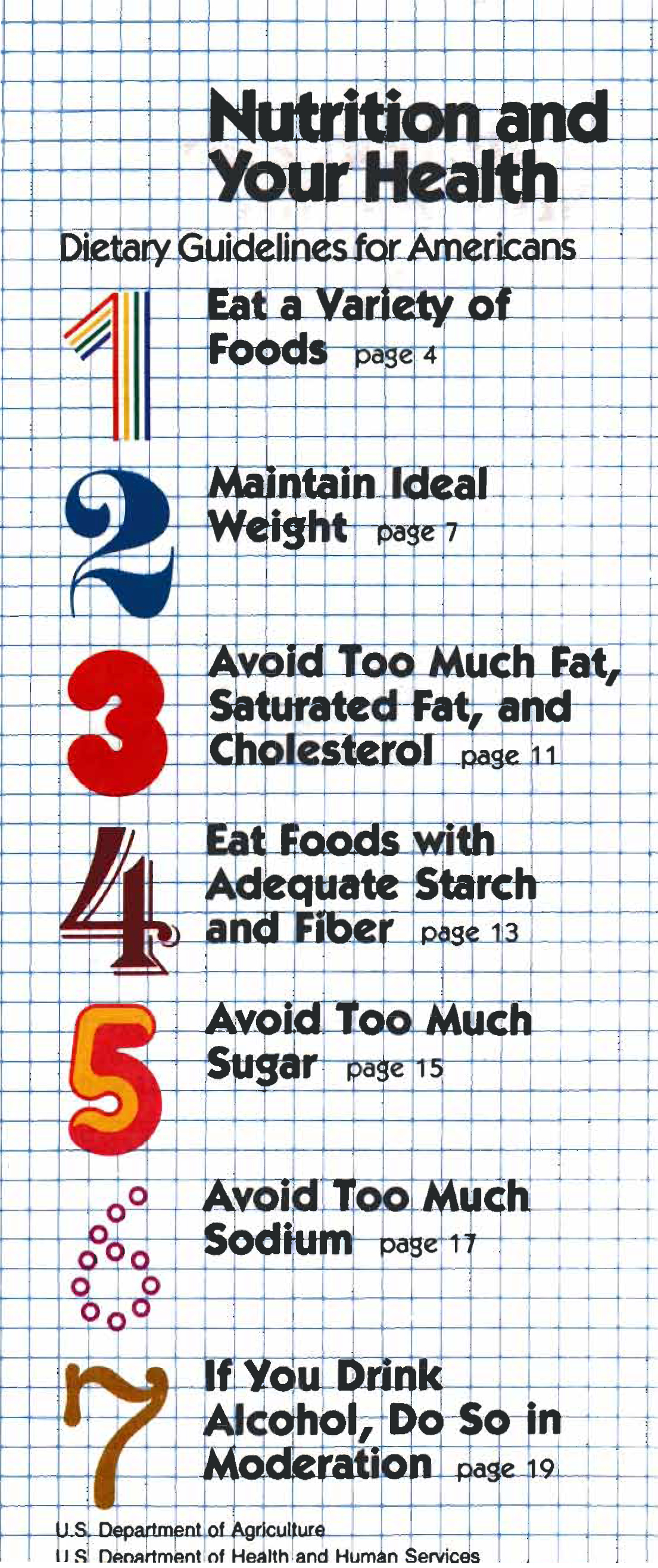

(Photo: United States Department of Agriculture)

Although the federal government has been putting out some form of nutritional guidance for a century (the USDA’s earliest food guide dates back to 1916), the idea that a federal agency should dictate the diet of Americans took a while to catch on. It picked up steam during World Wars I and II, when the USDA launched “patriotic propaganda” campaigns promoting certain foods, as nutrition advocate K. Dun Gifford wrote in the American Journal of Medicine. (“American meat is a fighting food,” read one pamphlet.) This later evolved into an effort to fight malnutrition, as new food-assistance programs emerged in the 1970s.

Finally, a landmark Senate committee acknowledged the need to advise a “confused” public in 1977. But when USDA and Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) officials published their first official guidelines in February of 1980, the document was ridiculed. “Do we know enough to eat well? [Federal agencies] apparently think they know enough to prescribe how the general public should eat,” the New York Times‘ personal health columnist Jane Brody wrote in 1980. It was more than hubris; scientists with the National Research Council came out against the advice of the government, further confusing the public.

Yet the guidelines soldiered on, growing more expansive, and purportedly more scientific, over the years. According to the USDA, the independent committee meets to review the scientific evidence on nutrition and distill its findings into a report that informs the guidelines. The guidelines have roused many more debates, as they have adjusted to allow for less cholesterol and more saturated fat, according to The Atlantic. But contrary to public opinion, the committee’s recommendations have remained fairly steady.

How the Food Industry Influences Nutrition Policy

Criticism has persisted, however, often because the guidelines—and nutrition science at large—have long been entangled with the food and beverage industry, which spent $29 billion on lobbying last year. (This is part of the reason that the HHS and the USDA now split the work of overseeing an outside committee, according to Time.)

Angela Amico, policy associate for the consumer watchdog group Center for Science in the Public Interest, says industry groups can delay public-heath recommendations by pushing what she calls “manufactured doubt.” This has played a role in everything from the tobacco wars to defense of added sugars in soda. “I don’t think all industry sponsorship of research is problematic, but it needs to be reviewed critically when there are those ties and really clear boundaries in place, and unfortunately that’s not always been the case,” Amico says. “It’s important to say, ‘Who’s funded this research? What do they have to gain?’ I think it’s clear that the food industry is going to continue to try to play a role in this process.”

These criticisms have already resurfaced in time for 2020. As nutritionists like New York University professor Marion Nestle have revealed, the food and beverage industry influences the dietary guidelines by backing nominees friendly to their cause and funding research that could be used to inform it. (In an analysis of this year’s committee, Politico‘s Helena Bottemiller Evich found that the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association and American Beverage Association both nominated two experts.)

The USDA, meanwhile, says that this process is data-driven and science-based. “This expert committee’s work in objectively evaluating the science is of the utmost importance to the departments and to this process,” Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue said in a statement announcing the nominees. “The committee will evaluate existing research and develop a report objectively, with an open mind.”

Red Meat’s ‘War’ Over Sustainability

But the meat industry has undoubtedly influenced who evaluates this research, and in what light. In 2015, questions over industry influence led to intense fights over high- and low-fat diets. The biggest casualty was a recommendation that you won’t find in the guidelines at all: the environmental impact of the food we eat.

Due in part to the efforts of one Tufts University nutritionist, Civil Eats reported, the 2015 committee concluded there was “consistent evidence” that a plant-based diet was healthier and had less of an impact on the environment than one high in meat, according to a 2015 article in Science. But a group of Republican senators asked the heads of the federal agencies to reconsider their stance—and the officials obliged. Despite the evidence, Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack and Secretary of Health and Human Services Sylvia Burwell concluded the guidelines were not “the appropriate vehicle for this important policy conversation about sustainability,” according to the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Frank Hu, professor of nutrition and epidemiology and chair of the Department of Nutrition at Harvard University, served on the 2015 committee and says the omission was due to “political pressure” from Congress, the meat industry, and special interest groups. “That was a missed opportunity, because our diet has an important influence on the environment and vice versa,” he says, noting that other countries have already included this in their national guidelines. “Our recommendations were completely avoided in the official guidelines.”

According to reports at the time, that’s putting it mildly: “Meat Industry Wins Round in War Over Federal Nutrition Advice,” one Politico headline proclaimed. Walter Willett, professor of epidemiology and nutrition at Harvard, condemned the decision as “censorship on a grand scale, again demonstrating the power of the meat industry to distort national policies and priorities.”

Yet Hu and others maintain that the highly politicized debate that informs the guidelines is not representative of the science at large. “Everyone thinks of herself or himself as an expert, because everyone eats, right?” Hu says. “There are a lot of sensational headlines in the media and a huge amount of misinformation and many claims about certain health benefits and adverse effects of certain diets. That has created a lot of confusion; it seems like no two nutrition scientists agree on anything. Of course, that’s not true.” One thing they do agree on: consuming lower amounts of processed meats.

If the federal government sidesteps sustainability once again in 2020, it won’t be based on any measure of food production’s true impact. The livestock industry, for example, accounts for much of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions and water and land use. As the committee takes on a new set of topics, wary of the political battles of 2015, this issue’s absence would mark another victory for special interests.