Another day, another instance of police misconduct caught on camera.

A YouTube video uploaded last week capturing a white police officer grabbing a 14-year-old bikini clad girl and drawing his weapon on unarmed teens at a rowdy pool party has sparked concern and outrage. Witnesses allege that the incident had racial undertones; white residents of the suburban tract in McKinney, Texas, allegedly told the mostly black partygoers to “go back to your Section 8 home.” The police followed suit: “You can see in part of the video where he tells us to sit down, and he kinda like skips over me and tells all my African-American friends to go sit down,” witness Brandon Brooks (who is white) told local media.

This is just the latest in a long string of similar incidents which, thanks to the presence of cell-phone toting bystanders, have drawn national outcry. Since the death of Eric Garner following a police chokehold in Staten Island last year, cameras have proven instrumental in documenting cases of officer misconduct. It was a bystander video that caught the cold-blooded murder of Walter Scott, also a black man, in South Carolina in April. (The white officer involved was indicted this week.) Cameras, it seems, are a citizen’s bulwark against police abuses. Even President Obama thought so, announcing $263 million in funding for 50,000 police body cameras last December.

This discomfort is an ironic inversion of law enforcement’s common refrain on surveillance: It’s not a big deal if you have nothing to hide.

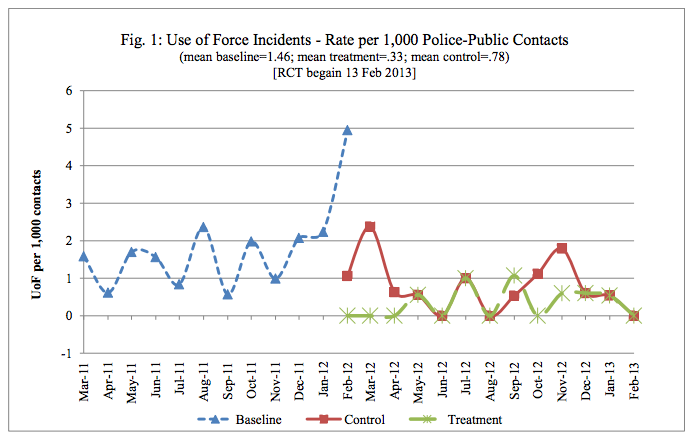

Recent research suggests that the presence of cameras can change officer behavior for the better. During a 12-month experiment conducted in Rialto, California, use-of-force by officers wearing body cameras fell by 59 percent, while reports against officers dropped by 87 percent compared to the previous year. A follow-up 2013 study by the non-profit Police Foundation, also in Rialto, found that equipping officers with body cameras made them more likely to think twice before deploying force, resulting in “a 50 percent reduction in the total number of incidents of use-of-force compared to control-conditions.”

But the presence of a camera isn’t a silver bullet for police misconduct. Despite the increasing ubiquity of cameras, instances of police abuse actually seem more prevalent than ever. Does the rise of our modern surveillance society make no difference? After all, the police are more likely to behave if they’re being watched, aren’t they?

It’s not that simple. Most police officers, focused on the task ahead of them, often don’t know they’re being recorded and show their true colors in the process. And even the mere presence of cell-phone video is more disconcerting to police than body cameras. “Cellphone videos taken by bystanders tend to make many police officers uncomfortable, because they have no control over the setting and often are not even aware they are being filmed until after an incident,” the Associated Press reported in April. This discomfort is an ironic inversion of law enforcement’s common refrain on surveillance: It’s not a big deal if you have nothing to hide.

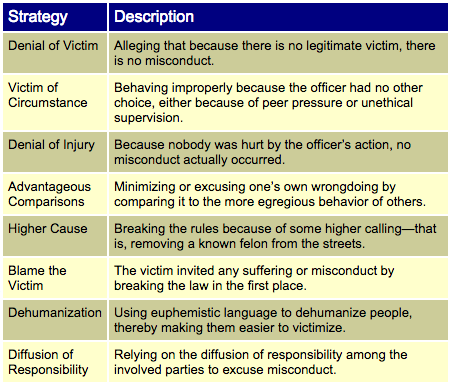

The presence of citizen surveillance does substantively matter, however. Cameras negate officers’ abilities to rationalize misconduct—be it accidental or intentional—that they may engage in during their daily work. This, in turn, makes many officers uncomfortable. According to research by Los Angeles criminologist Brian Fitch published in the Police Chief (an actual magazine), this notion of rationalization is a very real phenomenon among even the best and most well-intentioned police officers—when they make mistakes in the field, they often find ways to explain the problem away. And given the difficult decisions officers face in the course of daily life, some may fear that the camera deprives them of a necessary psychological mechanism to reconcile their actions and intentions.

“Decades of empirical research have supported the idea that whenever a person’s behaviors are inconsistent with their attitudes or beliefs, the individual will experience a state of psychological tension—a phenomenon referred to as cognitive dissonance,” Fitch explains. “Because this tension is uncomfortable, people will modify any contradictory beliefs or behaviors in ways intended to reduce or eliminate discomfort.”

The examples of rationalization in the table from Police Chief may seem familiar: They echo the excuses of law enforcement officers in highly public cases from the past year (the officer at the center of the McKinney pool party incident said he “feared for his own safety” when he grabbed a teenager by her hair). But phones might provide a way forward not just for police accountability, but for behavior as well. While the presence of your iPhone may not generate the same disincentive that a federally mandated body camera does, the message remains clear: You should be uncomfortable, because we’re watching you.