It turns out Americans may be able to frack where they eat after all.

The Environmental Protection Agency released a draft report Monday detailing the impact of hydraulic fracturing (or “fracking”) on drinking water, a long-standing concern among environmentalists and other opponents of the practice. The report, the result of a five-year analysis of scientific research and data on spills and leaks, “did not find evidence [of] widespread, systemic impacts on drinking water resources in the United States.”

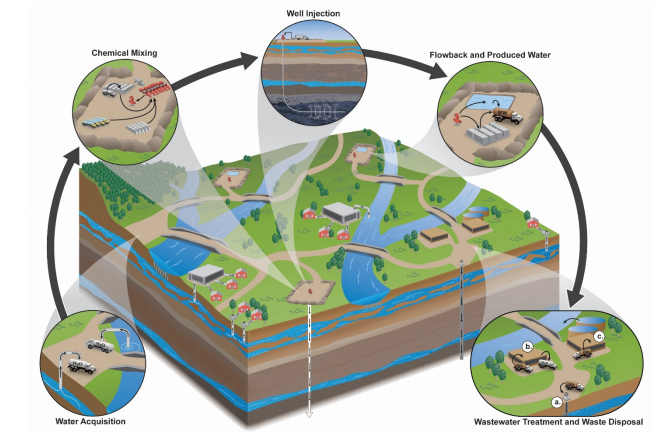

This may sound like a major blow to environmental arguments against the practice, which has gained in popularity among oil and gas companies as America attempts to wean itself off of foreign oil. While oil and gas companies have been fracking since the 1950s, an accelerating rate of drilling has raised alarm among conservationists concerned that the practice may have a devastating impact on nearby communities. Footage of a North Dakota man lighting his faucet on fire near a fracking site went viral in 2014, sparking anxiety that the practice could be slowly poisoning local communities. But the EPA report certainly identified a few areas of serious concern for regulators: “water withdrawals in times of, or in areas with, low water availability; spills of hydraulic fracturing fluids and produced water; fracturing directly into underground drinking water resources; below ground migration of liquids and gases; and inadequate treatment and discharge of water.”

The real problem for environmentalists at the heart of the EPA report is that the government can’t actually collect enough data to accurately measure the practice’s impact. And with the rate of fracking increasing—the EPA estimates that 25,000-30,000 new fracking wells were drilled annually in the U.S. between 2011 and 2014 alone—this could pose a tremendous problem for authorities looking to evaluate the rapidly growing industry. In fact, the EPA admits that the gas industry doesn’t even have a definitive tally of the number of active wells in the U.S. From the report:

The lack of a definitive well count particularly contributes to uncertainties regarding total water use or total wastewater volume estimates, and would limit any kind of cumulative impact assessment. Lack of specific information about private drinking water well locations and the depths of drinking water resources in relation to hydraulically fractured rock formations and well construction features (e.g., casing and cement) limits the ability to assess whether subsurface drinking water resources are isolated from hydraulically fractured oil and gas production wells. Finally, this assessment is a snapshot in time, and the industry is rapidly changing (e.g., the number of wells fractured, the location of activities, and the chemicals used). It is unclear how changes in industry practices could affect potential drinking water impacts in the future.

This scarcity of data means the EPA’s assessment, while thorough, is fundamentally flawed. As Inside Climate News‘ Neela Banerjee explained (via Mother Jones) back in March, definitive scientific research would have required baseline studies that “provide chemical snapshots of water immediately before and after fracking and then for a year or two afterward” to establish what “normal” chemical levels are in drinking water supplies and, in turn, set a standard by which to measure contamination of water in close proximity to oil and gas wells. This would be the most reliable way to determine whether oil and gas development contaminates surface water and nearby aquifers, and the findings could highlight industry practices that protect water.

But instead, oil and gas companies can now stonewall government officials and protect their rapidly growing new revenue streams. “Prospective studies were included in the EPA project’s final plan in 2010 and were still described as a possibility in a December 2012 progress report to Congress,” Banerjee explains, “but the EPA couldn’t legally force cooperation by oil and gas companies, almost all of which refused when the agency tried to persuade them.”

The government isn’t blind to the potential risks. In March, the Department of the Interior moved to establish new standards for oil and gas wells, including the disposal of toxic wastewater and the basic protection of community water supplies. But despite the government’s valiant five-year study, a nationwide assessment of fracking’s impact on drinking water—and what to do about it—is incomplete without more data.