Some of Los Angeles’ lowest-paid workers are about to get a big raise. The Los Angeles City Council voted Tuesday to approve raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour, Reuters reports, making the city the largest in the country to adopt such a high minimum wage.

The 14-1 vote, which officials told Reuters will raise the pay of some 800,000 workers in the metro Los Angeles area, follows months of political activity surrounding wages nationwide, ranging from President Obama’s 2014 legislative push to raise the federal minimum to wage to $10.10 and ongoing wage strikes by fast-food workers, the political face of wage increase advocates.

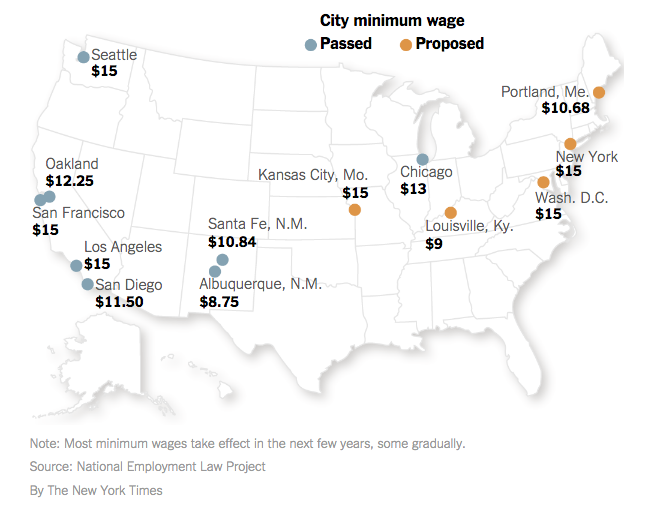

The American public seems in support of giving American workers a raise: A January 2015 poll showed that 75 percent of Americans (including 53 percent of Republicans) were in support of raising the federal minimum wage, and cities from Louisville, Kentucky, to New York City are considering proposals to match the minimum-wage hikes approved by the L.A. council.

Conservative critics of minimum-wage hikes argue that these raises will inevitably hurt small businesses, forcing employers to funnel money that could be used for hiring or expansion into paying existing employees—and even leading to layoffs. This makes logical sense, and a 2014 Congressional Budget Office report found Obama’s $10.10 minimum wage proposal, with a target implementation of 2016, would kill some 500,000 jobs nationally; even restricting the wage hike to $9.00 would still knock off some 100,000 jobs, according to the CBO. There’s recent empirical evidence too: Hiking the minimum wage from $5.15 to $7.25 may have kept one million people out of work when the Great Recession hit.

But University of California-Berkeley economist Michael Reich, who spearheaded the economic assessments of wage-hike proposals for both Seattle and Los Angeles, asserts that the conservative hand-wringing is overblown—and that the proposals in those two cities will prove them wrong once and for all.

“To date, three rigorous studies have examined the employment impacts of San Francisco’s and Santa Fe’s local minimum wage laws,” Reich wrote in his assessment for the city of Seattle. “Each finds no statistically significant negative effects on employment or hours (including in low-wage industries such as restaurants).”

For Reich, increased labor costs don’t immediately translate into job losses, but can be absorbed through other sources like improved efficiency and higher prices. In fact, research from the Center for Economic and Policy Research suggests that, in general, changes to the minimum wage have have no discernible effect on unemployment. Reich predicts that Los Angeles County will only shed some 5,262 jobs by the time wages climb to $15 an hour in 2020.

So what separates the depressed employment that occurred in 2007 and the CBO’s assessment of the Obama minimum wage plan from arguments by economists that the minimum wage doesn’t completely screw over employers? The obvious answer is time: The 2007 minimum wage hike and the Obama $10.10 proposal were designed for a two-year implementation, while wages in Seattle and Los Angeles won’t reach $15 an hour until 2020. That’s plenty of leeway to give employers time to build out the “channels for adjustment” that Reich identifies as so important for businesses to absorb costs: reductions in labor turnover, improvements in organizational efficiency; reductions in wages of higher earners, and small price increases.

There’s also the argument that America’s ongoing recovery will help create enough jobs to compensate for any losses by businesses that simply can’t adapt. Another recent CEPR study points out that 12 of the 13 states that implemented minimum-wage hikes on January 1 of 2014 still experienced employment growth, albeit at relatively slow rates, while the national unemployment rate dropped from 6.5 to 5.5 percent.

While changes in the minimum wage will certainly displace employees at businesses that simply can’t adjust to the sudden change in costs, it’s statistically and factually incorrect to argue that a $15 minimum wage will throw the brakes on economic growth in the United States. Then again, time will tell; even economists like Reich recognize that Seattle and Los Angeles are grand experiments. But this, Reich says, is the point: After all, “modern economics therefore regards the employment effect of a minimum wage increase as a question that is not decided by theory, but by empirical testing.” We’ll see if the businesses of Seattle and Los Angeles are up to the challenge.