In January of 2014, I started getting text messages from my college friends asking whether I was following our old classmate Arthur Chu on Jeopardy! I wasn’t—I hadn’t watched the show for years—but I tuned in the next day.

From then on, I watched rapt as Chu racked up what was, at the time, the third-longest winning streak in the show’s history, drawing attention not only for the size of his haul (almost $400,000 in the end), but also for his supremely stereotypical nerdiness. He used an unorthodox strategy that drew on both game theory and statistical analysis of the Jeopardy! board. He was slightly pudgy, with glasses, and his hair was cut in a harsh horizontal line across his forehead. His shirts were rumpled, his ties poorly knotted. He spoke in a monotone and sometimes interrupted Jeopardy! host Alex Trebek, cutting off Trebek’s patter so they could move on to the next question.

I had barely known Chu in college, but I loved watching him win. He seemed to simultaneously embody nerd stereotypes and vindicate them—by raking in a fortune. I especially liked his attitude toward his detractors: When people mocked him on Twitter, he re-tweeted their jibes, as if to demonstrate how little they hurt.

After Chu’s run ended, I found myself missing it. Several months later, checking his Twitter feed, I saw him announce he would be appearing on a panel at a gaming convention in Maryland called MAGFest, where he would be talking about “the general unpleasantness in the nerd community this year,” including “the #Gamergate fiasco.” This had the ring of familiarity, but I would have been hard pressed to say what any of it meant.

It didn’t take much research for me to pick up that 2014 had been a tumultuous year in American nerd-dom. Long-simmering tensions built into the very concept of “the nerd” had reached a boiling point, with shockingly vicious results: death threats, rape threats, and torrents of online abuse, most of them made by nerds themselves against those perceived to be finding fault with nerd culture.

To my surprise, some of the most interesting and well-circulated analyses of the mayhem had been written by none other than Arthur Chu, who had leveraged his 15 minutes of game-show fame into, of all things, a national platform for his opinions about nerds: What America gets wrong about nerds; what nerds—especially male nerds—get wrong about themselves; and why it matters. In Chu’s view, nerd-dom has a toxic, intolerant fringe, one that has gone unchecked in large part because nerds are awful at policing their own subculture, especially online. In an era when the nerds are increasingly ascendant, Chu wants to make nerd culture better—and to stop more of his fellow nerds from getting drawn into the worst of it.

In his MAGFest post, Chu asked his fans to come give him moral support. Debates about nerd-dom, he wrote, had recently become “a lot scarier.”

A few days later, I bought a pass to the convention.

When I met Chu in person at MAGFest—almost eight years since we’d been college students together—I was struck by how different he looked, not only from our college days but from when I’d first seen him on Jeopardy! He’d lost 30 pounds, gotten a more stylish haircut, and ditched his glasses, thanks to free LASIK surgery performed by a Cleveland-area eye clinic in exchange for his celebrity endorsement.

Chu seemed as shocked as anyone by his trajectory. “I didn’t have any idea that I would win that much,” he told me. “And then when I did, I didn’t have any idea that it would cause this much attention. That was a one-two-punch kind of thing.”

But, as several of his old friends have pointed out to me, Chu has been arguing with his fellow nerds for a long time, often in endless middle-of-the-night Facebook and message board posts. “I have a hard time letting things go,” he admits. Jeopardy! has let him do something he’s always done—just for money, and for a lot more readers.

“It’s been a little uncanny,” says his college roommate, Greg Robinson, who recalls an old joke he and Chu had between them: “If Arthur could find a way to monetize arguing on the Internet, that would be his career. He’d be set for life.”

Before Jeopardy!, Chu was working as an insurance compliance analyst in Broadview Heights, a small city outside of Cleveland, where he also acted and did improv on the side. Waiting for his Jeopardy! episodes, which were pre-taped, to air, he hoped that the publicity might help him get gigs as a voice actor, a side career he’s been trying to build for years. (It sounded quixotic to me, until Chu told me he’d had several voice-over gigs already, including a video for Safeway.)

When the Jeopardy! episodes were broadcast, they triggered a tsunami of media attention. Chu had never anticipated that people would care so much about his clothes, weight, or way of speaking. It was his introduction to a peculiarly modern form of exposure, one in which you can watch in real time as thousands of people entertain themselves by talking about you as if you weren’t there. Some deemed Chu smug; others opted for digs about his weight. (“Looks like he just ate a pizza in bed,” tweeted one non-fan.) Many deemed his aggressively money-focused strategy unsportsmanlike. The media started calling him “the Jeopardy! villain.”

But the notoriety also had more agreeable results. Chu gained fans, many of them Asian Americans happy to see a nerdy Chinese American kicking unapologetic ass on the national stage. TV shows wanted to interview Chu, and reporters wanted to profile him. Chu said yes to almost everything, intrigued by the possibility of finding his way into a new career—something, he told me, “that sort of goes with the rhythm of my interests, instead of getting orders from corporations.” He thought it was absurd that a person could get famous from a game show, but—as he puts it in the trailer for Who Is Arthur Chu?, an upcoming documentary—“I’d rather be famous for that than for nothing.”

Chu also began to find his voice as a writer, as Web publications took an interest in his byline. In May, Chu was asked to review The Big Bang Theory, the popular sitcom about nerds, for the Daily Beast. It was his fourth assignment for the site (on which his author bio describes him as a “Chinese-American nerd” who is “shamelessly extending his presence in the national spotlight by all available means”). But Chu never wrote the review. On the Friday before it was due, a 22-year-old named Elliot Rodger went on a violent rampage in Isla Vista, California, killing six people and injuring 14 others before committing suicide. On the day of his killings, Rodger had emailed a 141-page manifesto to family and acquaintances that described the violence he was about to commit as revenge on the female gender for ruining his life and on sexually active men for besting him.

When Chu read Rodger’s manifesto, he found much of it to be terribly familiar. Except for the parts about murder, it read like a standard-issue litany of complaints by a lonely male nerd blaming women for his loneliness. “It’s all girls’ fault for not having any sexual attraction towards me,” Rodger wrote. Instead of writing a review of The Big Bang Theory, Chu stayed up past dawn writing a different piece—an angry one—in which he insisted that, though Rodger was mentally ill, his attitudes toward women were common, especially among aggrieved male nerds. Chu confessed to having spent much of his own life as a lonely nerd and to having contributed to a culture that excused bad behavior. He said he had known nerdy male stalkers, even nerdy male rapists, but to his disgust had never confronted them.

“So, a question, to my fellow male nerds,” he wrote. “What the fuck is wrong with us?”

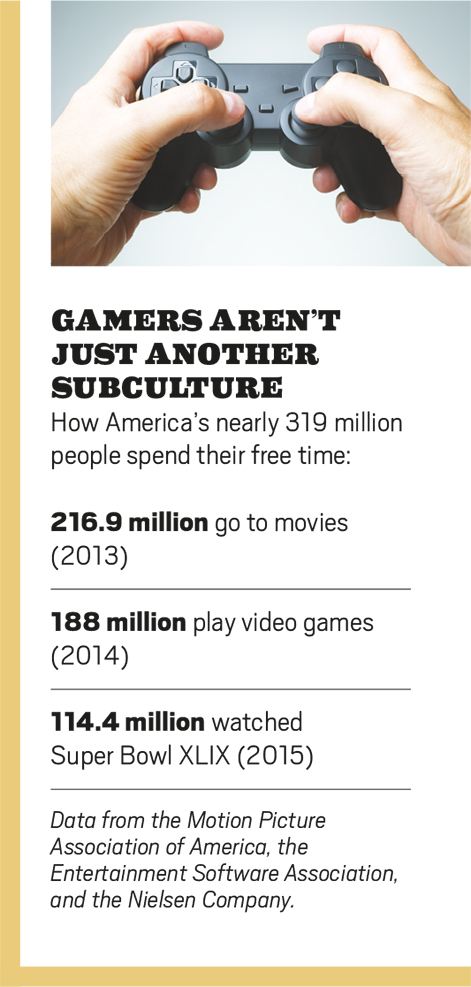

The term “nerd” has come a long way since the 1980s, when it simply denoted an awkward social loser, usually a bespectacled, physically graceless male too book-smart for his own good. Today, it encompasses ever more subtypes: the loser; the intense (or even just mildly intense) fan of this or that pop-culture phenomenon; and the wealthy Silicon Valley coder or CEO wielding power over the American zeitgeist. The idea that “we are all nerds now” is increasingly common: See the Guardian in 2003, New York magazine in 2005, Esquire in 2013, and the New York Times last year.

Chu recognizes that many nerds are thriving in the post-industrial economy and that many once-nerdy interests are now mainstream. But he is careful to stress that the more painful variety of nerd-dom, the kind you don’t adopt by choice, still exists. He knows there is still such a thing as not fitting in, or being unable to get a date. And he knows how much it sucks, because he’s been there himself.

Chu’s parents are fundamentalist Christians who immigrated to America from Taiwan. They lived in Rhode Island until Chu was 12, then moved to Boise, and by the time Chu was in high school they had settled in Cerritos, California, near Los Angeles. “Growing up evangelical was a real double bind,” he says. He didn’t accept religion easily, arguing the fine points of C.S. Lewis with his Sunday school teachers, which made him an outsider in the evangelical community. Meanwhile, being an evangelical Christian—not to mention an Asian-American child with an advanced vocabulary and precise diction—marked him as an outsider everywhere else.

“I was the kid who probably spent fully 10 times as many hours reading books at school [as] exchanging words with any of my classmates,” he wrote last year in Salon. “It was years before I learned to talk something like a normal human being and not an overly precise computerized parody of a ‘nerd voice.’ People felt uncomfortable around me, disliked me instinctively.”

Chu joined a clique of what he calls “bitter angry guys” who desperately wanted female attention and felt antipathy toward women for not giving it to them. Even when Chu managed to get a high school girlfriend, he resented her for being, as he saw it, above him, as an automatic result of being female. He says he and his friends had “tunnel vision” and couldn’t understand that “it could suck to be sexually wanted as much as to be sexually invisible.”

After high school, he moved east to attend Swarthmore, a Pennsylvania liberal arts college with fewer than 1,600 students. He promptly joined a storied campus club, devoted to science fiction, fantasy, and the general embrace of nerd-dom, called SWIL—the Swarthmore Warders of Imaginative Literature. Chu felt he’d arrived in utopia: an in-the-flesh version of the online message boards he’d frequented through high school.

But SWIL did not feel so welcoming to all of its members. Chu says several male SWILlies were guilty of behavior that ranged from off-putting (sexist jokes) to predatory (dating a local high school student). A larger group of SWILlies turned a blind eye to it. In Chu’s view, this was because of nerd indulgence, born of a reluctance among people who have been ostracized to set standards that might exclude others. What one group of SWILlies viewed as misogyny and harassment got written off by the other group of SWILlies as awkwardness, or autism, or misunderstanding. (Both factions were made up of males and females.)

By his own reckoning, Chu spent most of college as part of the second group. But over time, thanks in part to friendships with some of the female SWILlies who felt uncomfortable, he came to think the club had a problem. Among the issues were club events that attracted creepy alumni—guys who had a habit of, as Chu puts it, “serially sleeping” with freshmen—and, in 2007, a group of reformers within SWIL voted not only to change the club’s name (to Psi Phi—get it?) but also to ban alumni from its meetings and parties, an act of nerd exclusion that caused serious rifts among club members. Chu strongly supported the ban, eagerly debating its merits. (Jillian Waldman, who was co-president of SWIL in 2004 and 2005, disputes Chu’s characterizations of “old-school SWIL,” which she says was the more tolerant club.)

The SWIL civil war coincided with a general unraveling in the rest of Chu’s life. Freed from his strict home, Chu was suddenly free to stay up all night playing video games, fine-tuning the SWIL newsletter, writing his campus newspaper column (“Chu on This”), editing Wikipedia articles, and indulging his insatiable appetite for debate on any subject under the sun. He was also spending more and more time in campus theater productions.

Chu’s GPA dropped, and he got kicked out of a seminar, setting in motion a chain reaction that made him unable to graduate on time. He spent an extra year living in Philadelphia and taking classes, and another finishing his course work from his parents’ house in California. He used the public library there to research his thesis and to try to launch his voice-over career, or, when that didn’t work, to just find a job, any job, in the crashing economy. He sank into depression, played too many video games, and wondered how much longer he could go on.

Chu’s choice last May to surprise his Daily Beast editor with an article about nerds and the Isla Vista killings ended up paying off. Headlined “Your Princess Is in Another Castle,” a reference to Super Mario Bros., the article went viral. Chu started getting calls from the media once more. This time, CNN and NPR didn’t want to talk about his “Daily Double” Jeopardy! strategy. They wanted to hear about “nerd lust.”

Chu found himself with a new sense of purpose. Other people had made similar observations about nerd culture before, but thanks to Jeopardy!, Chu had a shot at taking the issues to a bigger audience. In the months that followed, he wrote more about the dark currents within nerd-dom. One article discussed nerd power-lust. (“The creepy nerd fantasy that remains alive and well in today’s Age of the Nerd Triumphant is not of making peace with the popular kids but taking their throne.”) Another called out blockbusters like Game of Thrones and Avatar for nerd ethnic chauvinism. (“We repeatedly tell stories about a white protagonist who goes on a journey of self-discovery by mingling with exotic brown foreigners and becoming better at said foreigners’ culture than they themselves are.”)

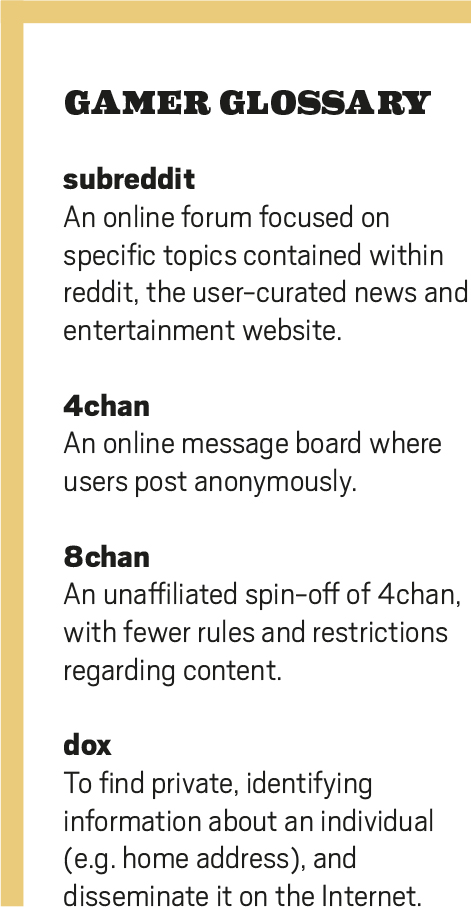

Then came the controversy dubbed Gamergate, which was to raise Chu’s profile even further. To explain Gamergate simply—or at all—is no easy task, but it began last August, when a 24-year-old man named Eron Gjoni posted a rambling, 9,000-plus-word blog post about the game developer Zoe Quinn, an ex-girlfriend whom he accused of cheating on him with a video-game journalist in order to advance her career. Quinn had often criticized the way women are portrayed and treated by mainstream gaming culture, so a contingent of hardcore gamers viewed Gjoni’s allegations against her as emblematic of a corrupt journalistic culture that was out to undermine traditional games that were fun but non-PC: too violent, the bad guys too dark-skinned, the women too scantily clad. The angriest of them bombarded Quinn with online harassment, including death and rape threats. Some of Quinn’s detractors broke into her accounts for online services like Tumblr, posted nude photos of her, and published her home address, leading her to move out of her residence. Online campaigns also sprang up targeting other female game developers and gaming writers.

Chu was horrified by the online Gamergate mobs, but also energized. He sparred with Gamergate supporters—meaning those who sided with gamers against people like Quinn—on Twitter, and he wrote articles categorizing Gamergate supporters as part of a “reactionary” movement doomed to eventual failure. If his hope was to become a nerd pundit, here was the ideal cultural moment.

Chu often stressed that he understood firsthand the pain of persistent social and romantic rejection. He assured readers that he, too, loved video games and well knew how powerful a refuge they could provide. But he also insisted that not all injustices merit equal pity. Yes, he wrote, he sympathized with some of the aggrieved feelings out there, but he could not endorse the self-pitying militancy they generated, calling it a “toxic swell of nerd entitlement that’s busy destroying everything I love.”

As had happened with Jeopardy!, the online attention came with burdens. To Gamergaters, Chu had thrown his lot in with the “social justice warriors” (or “SJWs”), a pejorative term for people who appropriate the language of minority struggles in the pursuit of their own renown. They made cartoons portraying him as a puppet of gaming feminists. In a different line of attack, they jumped on Chu’s claims about having known nerdy rapists, circulating articles that labeled him a “rape apologist” and “rape enabler.” But Chu also got closer to a new career. He started booking college speaking gigs and workshops, which allowed him to go down to half time at his insurance job (he has since quit altogether) and to sign with a literary agent, with whom he is preparing a proposal for a book that will be part Jeopardy! memoir, part meditation on contemporary nerd-dom and its relationship to the Internet.

In Chu’s view, nerds created much of what we love about Internet culture but also much of what we hate about it. Intended as a refuge from real-world hierarchies and prejudices, the Internet has often wound up simply reproducing, even exaggerating, the power dynamics of the “real world,” complete with bullying. Chu feels that if nerds were more willing to set some community standards, like the SWILlies did at Swarthmore, and behave with less indifference to the worst of their peers, they could make the world a lot more pleasant and protect the best of nerdiness—the joyful obsessions, the embrace of outsiders, the indifference to convention.

One challenge for Chu’s conversion efforts is that he has trouble accounting for his own recovery from nerdy bitterness. When I asked him about this during one of our conversations, he shook his head, looking genuinely mystified. “I don’t know,” he said. “That’s, you know, ‘there but for the grace of God.’” But he was quick to point to one development his younger, angrier self could barely have imagined: wedlock.

Chu met his wife-to-be, Eliza Blair, at Swarthmore during his sophomore year; she was one of the SWILlies (a co-president, eventually) who led the reform charge. They didn’t hit it off. “He was a huge blowhard jerk and I hated him on sight,” she wrote me in an email. “It was all insecurity, immaturity.”

Over time, though, Blair became Chu’s biggest fan. In 2006, she made drawings of all her SWIL friends, representing their futures. Chu was depicted standing on a podium, speaking to an enthralled audience of thousands. “I knew that under the shitty nerd veneer was a guy with a lot of depth and a lot to say about the way the world works,” Blair wrote. “I loved that guy and wanted to give him every chance to succeed.”

Blair graduated in 2007, and she and Chu stayed in touch, she from Washington, D.C., and he from Cerritos, while he salvaged his undergraduate degree. Blair, too, was struggling with life—with the gap between the post-college future she’d been told to expect and the reality she encountered. The correspondence developed into a long-distance courtship. Eventually, Blair got a job at the EPA, and Chu decided to join her in Washington, where they moved in together. At first, Blair supported Chu while he tried to get a decent job. When no such job materialized, he worked as a tour guide, then as a salesman of IT products he didn’t care about.

The couple attended their first MAGFest—the name stands for Music and Gaming Festival—in 2010. The next year, at MAGFest 9, Chu orchestrated an elaborate, convention-wide scavenger hunt for Blair that culminated in a video-game challenge: to beat a final boss in the Sega Genesis classic Sonic 3 & Knuckles. When she won, Chu’s face popped up on screen, asking her to marry him. He was down on one knee behind her, waiting for an answer. She said yes.

In 2013, a Blair family friend who owned an insurance company in Cleveland offered Chu a job as a claims analyst. It wasn’t the type of job he would have imagined while at Swarthmore, but now he jumped on it. Chu wanted to take a turn as primary breadwinner, enabling Blair, who suffers from the chronic pain disorder fibromyalgia, to get some work done on a long-planned science fiction novel. To Chu’s surprise, he liked Cleveland. The city was cheap, and because it was small, it was easier to get cast in local theater projects. “I was thinking, OK, I can do this, I can have a normal life,” he recalls.

No one will ever know the hypothetical Arthur Chu who never reconnected with Eliza Blair and got his life together. But part of his appeal, both in his articles and in person, is the sense that he carries this grim hypothetical self around with him, aware of how easily it might have won the upper hand. He often seems to be winking at these almost-Arthurs, taunting them for having failed to eat him alive. And his best articles suggest to people reading not only that they, too, have hard choices to make, but also that they just might be capable of making the right ones.

The morning of Chu’s appearance on the MAGFest panel, I met him in the atrium of the Gaylord National, which is billed as the largest non-casino hotel on the East Coast, just across the Potomac River from Alexandria, Virginia. MAGFest has convened there since 2012. Over 17,000 people were in attendance, and while Chu and I sat on a bench and talked (and the Who Is Arthur Chu? crew filmed us talking), a continuous stream of people passed us by, many dressed as their favorite characters—Ms. Pac-Man, Captain Kirk, Han Solo, Wonder Woman, numerous anime personalities.

Chu was wearing a black MAGFest T-shirt and black sweatpants, one leg of which was lodged in his sock above the ankle. He told me he couldn’t decide if he was nervous. Posters on the message board 8chan, a notorious breeding ground for Gamergate-related harassment campaigns, had been discussing the possibility of disrupting the panel—now officially titled “Toxic Rage in the Gaming Community”—through coordinated domination of the question-and-answer period. A gaming journalist named Angelo D’Argenio had backed out of the panel, citing safety concerns.

Chu said part of him was preparing for aggressive non-questions. Part of him thought that Internet trolls were unlikely to show in real life. Part of him wondered if anyone was going to show at all. “We’ll see,” he shrugged. While Chu’s writing is passionate, insistent, and confessional, his offstage manner seems to oscillate between calm, light amusement, and boredom.

A few hours later, the room for the “Toxic Rage” panel had reached its capacity of 120 people, and more were being turned away at the door. At the other MAGFest panels I’d attended, the spirit had been distinctly celebratory: We’re all here to celebrate loving the same stuff! But this crowd felt apprehensive, as if each of its members was worried about his neighbors’ motives. A strong showing of convention security didn’t lighten the mood.

Chu was sitting on the stage with two co-panelists (there was no moderator). On his right was Oliver Surpless, a well-known MAGFest regular, and on his left was Elisa Melendez, a doctoral candidate in sociology who studies games. “Quite frankly,” she said in her introduction, fighting back tears, “I’m terrified of being in this room right now, and that’s why we need to talk about it.”

On the Internet, any open conversation about Gamergate provokes a savage barrage. But as the panel progressed, it became clear that the room wasn’t the Internet, everyone inside it was going to behave, and no one was going to burst through the door yelling death threats or claiming that gaming had been overrun by a feminist cabal. The tension gave way to relief, even exuberance: Maybe there are more of us sane nerds than there are of them.

Chu and his co-panelists spent most of their time taking questions, many from young men asking about the best way to make nerd culture a better place for women, or how to best respond to Gamergate arguments online. When the panel reached its scheduled end time, it was obvious that people wanted to keep going, and the panelists invited everyone to return in 90 minutes, when the room would be free again. About a third of the audience did.

Round two felt less like a panel and more like a free-flowing conversation, with many of the contributions coming from women. One said she had “30 geeky T-shirts at home,” each expressing her love for a video game or movie, but hadn’t brought any to MAGFest for fear of being approached by men looking to quiz her and find out if she was a “real” fan. Another teared up while recalling how, when she was harassed by fellow gamers online, her then-husband told her to “toughen up.” She later told me she had quit playing for many years.

Chu has seen enough of the world to know he can’t convince Gamergate obsessives that their outrage is absurd. Indeed, despite his love of debate, he has only limited faith in argument per se, which is one reason he has softened since college on his view of activists, whom he used to disdain because they weren’t as committed as he was to exhaustive skeptical argument. If lonely nerds are to be wooed away from defeatism and rage, he believes, they must be reached with camaraderie as much as reason. “You can have someone who wants to be a good role model for you,” Chu says, “but if they don’t speak the same language, you’re just not going to take influence from them.”

At the reconvened MAGFest panel, it was clear that people were speaking the same language, reveling in both the debate and the shared obsessions. Chu stayed on stage for two hours more, then announced that he wanted a drink and invited anyone who wanted to keep talking upstairs to a hotel suite. A dozen nerds skipped the video-game hall, the board- and card-game rooms, and the live-action roleplay zone and instead squeezed into an elevator together and headed up to keep debating, college-style, nerd culture’s glory and excesses, its past and future. It felt optimistic, passionate, welcoming, and, sure, a little awkward: Chu’s ideals made manifest. There was music playing from tiny laptop speakers, and someone had set up a disco ball. The crowd stayed for hours, nerding into the night.

Submit your response to this story to letters@psmag.com. If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state. Letters may be edited for length and clarity, and may be published in any medium.

For more from Pacific Standard on the science of society, and to support our work, sign up for our email newsletter and subscribe to our bimonthly magazine, where this piece originally appeared. Digital editions are available in the App Store (iPad) and on Zinio (Android, iPad, PC/MAC, iPhone, and Win8), Amazon, and Google Play (Android).