The Brothers: The Road to an American Tragedy

Masha Gessen

Riverhead Books

Tamerlan Tsarnaev was born in 1986 in the Russian Republic of Kalmykia. His mother, Zubeidat, was loving and determined to be “perfect” in rearing him, according to Masha Gessen’s new book, The Brothers, about Tamerlan and his younger brother Dzhokhar, the Boston Marathon bombers. Tamerlan was an easy child, responsible and well behaved. By first grade, in the early 1990s, he had become a model student: well dressed, “polite to a fault,” high achieving, smart.

In the late 1980s and ’90s, the Tsarnaev family moved peripatetically across Central Asia. Tamerlan’s father, Anzor Tsarnaev, an ethnic Chechen, grew up in Tokmok, Kyrgyzstan, among a community exiled there by Joseph Stalin in 1944. After Tamerlan’s birth, the family traveled from Kalmykia back to Tokmok; in 1992, to Chiry-Yurt, Chechnya; in 1994, as the first Chechan War erupted, they returned to Tokmok again, and then, when Tokmok itself became unsafe, to Makhachkala, Dagestan, where Zubeidat was raised. Anzor, a mechanic, was probably fencing stolen cars and likely ran afoul of the authorities or criminals, so in 2002, Zubeidat, Anzor, and Dzhokhar, moved to the United States. In 2003, Tamerlan and his two sisters joined them.

Life in the U.S. was not much easier than life in Central Asia, but the Tsarnaevs were accustomed to upheaval. The Chechen community in greater Boston was small but close. Anzor’s sister helped the family find a place to live, in a triple-decker in Cambridge owned by a woman named Joanna Herlihy. Dzhokhar, who Gessen’s sources describe almost universally as sweet and popular, assimilated immediately. Zubeidat learned English and landed a role translating documents for Harvard Law School, and told Herlihy that she planned to attend. That never happened, but she did go to hair-dressing school and found work at a nearby salon. Tamerlan, a novice fighter, won a boxing tournament shortly after arriving in the U.S. The family was eventually granted asylum, allowing them to receive public assistance. For several years all four children attended local schools, which, in Cambridge, are accepting of immigrant families.

“It is about something that, whatever evidence is unearthed, will never be entirely certain: it is about the tragedy that preceded the bombing, the reasons that led to it, and its invisible victims.”

Still, things unraveled. Zubeidat lost her job in 2008. Anzor worked as an unlicensed mechanic, did not make much money, and probably drank a good deal. The daughters, Bella and Ailina, married and had children in their teens, then divorced their husbands. Tamerlan applied to the University of Massachusetts-Boston, was rejected, and later dropped out of a community college. He delivered pizza, sold pot, and had a child. He seems to have enjoyed reading but chose his texts poorly: The Protocols of Zion and several anti-Semitic newspapers. Zubeidat and Anzor divorced in 2011 and Anzor returned to Dagestan. In 2012, Zubeidat was arrested for shoplifting and left the U.S. too. Herlihy threated Tamerlan with eviction. Only Dzhokhar, who moved for college, remained mostly on track.

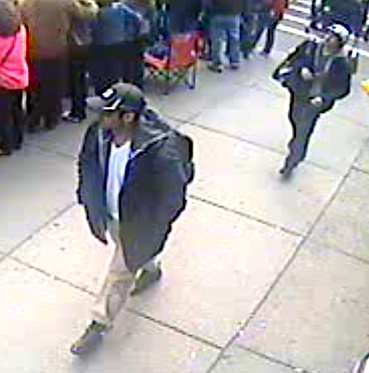

In 2013, Tamerlan and Dzhokhar planted two bombs near the finish line of the Boston Marathon, killing three people and wounding 264 others. Three days later they murdered a police officer. Tamerlan eventually died in a shootout, while Dzhokhar briefly escaped and was found hiding in a boat in Watertown. The bombings have been described as the worst act of terror in the U.S. since September 11th. Last week a jury in Boston found Dzhokhar guilty on 30 charges related to the bombings. A separate hearing to determine whether he will be sentenced to death begins on April 21, one day after the 2015 marathon.

The Brothers is Gessen’s seventh book and one of several substantial works of journalism about the bombings. It is not, as Gessen writes in a brief introductory note, about the pain inflicted by the attack. With the exception of Sean Collier, the police officer, the names of the Tsarnaevs’ victims never appear in The Brothers. “It is about something that, whatever evidence is unearthed, will never be entirely certain: it is about the tragedy that preceded the bombing, the reasons that led to it, and its invisible victims,” Gessen writes.

Why did the Tsarnaevs bomb the marathon? Two theories predominate. The first, that Tamerlan became radicalized and embraced violent jihad, comes from the FBI. Almost immediately after the police identified Tamerlan and Dzhokhar, in the early hours following the shootout, the agency launched a campaign of harassment against the brothers’ friends and acquaintances, evidently looking for conspirators.

Nearly a third of The Brothers is given to recounting these investigations and prosecutions. One case stands out. In May 2014, after a year of surveillance, the FBI arrested Khairullozhon Matanov, a Russian emigrant. Matanov, a cab driver granted political asylum in the U.S., had been friendly with Tamerlan, and had eaten dinner with the brothers on the evening of the bombing. He had no foreknowledge of their plans, and no idea that they had been involved until seeing their faces on TV, along with the rest of us, on Thursday, April 18. The next day, he drove to a police station in Braintree and reported what he knew.

In his statement to an officer there, Matanov lied about having seen the brothers on the news. (He may have mistakenly believed that he had a legal responsibly to report his recognition immediately, instead of waiting until the next day.) Matanov later cleared the browser history on his laptop, which showed that he had visited jihadi-sympathetic websites in the past (also not illegal). Clearing his cache and lying to the officer became the basis for the federal obstruction of justice and false-statement charges. (Why did prosecutors wait so long to arrest Matanov? Gessen believes the FBI was angered because he gave a cab ride to the father of one of Dzhokhar’s roommates in May 2014.) “The whole case is mystery,” Matanov told journalist Susan Zalkind. “FBI is trying to destroy my life.”

Last month, facing 20 years in prison, Matanov pleaded guilty in exchange for a reduced sentence of 30 months, with 10 months served. Zalkind records this conversation between Matanov and Judge William Young:

“You’re afraid if you go to trial you could be found guilty of all four of these charges and the sentence might be longer than the 30 months?” Judge Young asked. “Is that it? That you think you are not a guilty person but given the circumstances you’d rather [not] go to trial?”

Matanov’s dark bowl cut bobbed slightly. “I signed a deal and I found guilt most fitting for my situation.”

The other investigations have resulted in convictions for three of Dzhokhar’s college friends and the deportations of at least eight people with ties to the brothers or the broader Chechen-American community. In May 2013, an FBI agent shot and killed a Chechen native named Ibragim Todashev, after he attacked the FBI agent and a Massachusetts State Trooper during an interview in Florida. None of these individuals are suspected of planning violent acts, or of having known of the bombings before anyone else.

The second theory about the brothers’ motivation was largely advanced by the Boston Globe, which published a long and widely praised story on the Tsarnaevs in December 2013.

In the Globe’s analysis, “the motivation for the Tsarnaev brothers’ violent acts is more likely rooted in the turbulent collapse of their family and their escalating personal and collective failures.” Zubeidat is presented as hysterical and unhinged; Tamerlan as a possible schizophrenic and a conspiracy theorist with an “intimidating aura.” Anzor and Zubeidat are deviant and neglectful parents who married off Ailina and Bella as teens and did not attend Dzhokhar’s middle school graduation. Long stretches are devoted to Tamerlan’s visits to mosques in Cambridge and Dagestan.

Gessen, who emigrated from Russia to Massachusetts as a teen, is at pains to distinguish the family’s real pathologies—its inability to ever settle down, anywhere—from the more numerous and prosaic ways in which it may have seemed different because it was foreign. There is little evidence that Tamerlan suffered from a psychological disorder, Gessen argues. Zubeidat was most likely laid off from her job not because of her increasing religiosity but because the salon where she worked went out of business. Dzhokhar didn’t want his parents to attend his graduation—he could pass as native born and asked Herlihy, the landlord, instead. Tamerlan became religious but was hardly pious. Ailina’s marriage was arranged, which was not unusual for a young Chechan woman, though her refusal to marry her father’s first choice indicated that Anzor was willing to compromise—as did both sisters’ later divorces.

The Tsarnaev family’s disorder was related to the bombing, but in the sense that it falls into a category common to both terrorists and millions of normal young men across the world. Gessen neatly summarizes the sociological research on terrorist profiles and finds that Tamerlan fits: he was in his twenties, an immigrant, and educated but marginalized. Most of these men do not commit acts of terrorism, though, just as most despairing American teens do not commit school shootings.

Are Tamerlan’s conspiracy theories easier to understand in context? In 1999, Vladimir Putin is believed to have orchestrated a series of apartment bombings in Russia as a pretext for launching the second Chechen War. That a young Chechen man might struggle to accept government narratives about terrorism isn’t surprising. And in some of Gessen’s slyest sections, she alludes to similarities between Russia’s treatment of ethnic and religious minorities in Central Asia and the U.S.’s treatment of immigrants and Muslims. From the Tsarnaevs’ perspective the two governments may not have seemed terribly different.

In 2012, Tamerlan traveled to the Russian republic of Dagestan, where he became close with a friend of his cousin, a man named Mohammed Gadzhiev, deputy head of an organization called the Union of the Just. Russian security forces have been fighting a low-intensity but brutal war against Salafi Muslims in Dagestan for several years. The Union of the Just is ideologically aligned with the Salafists but, as a public organization, probably not involved in violence. Here is what Gessen reports about Tsarnaev’s relationship with Gadzhiev, whom she interviewed at length:

In the end it seems that most of what Tsarnaev did during his six months in Dagestan was talk. Talking—and having someone not only listen to what he had to say but also take it seriously enough to question and criticize and try to guide him—was a radically new experience for him….

Gadzhiev found [Tamerlan’s] knowledge of the Koran cursory at best. He appreciated that Tamerlan claimed being a Muslim as his primary identity, but criticized him for vague statements and uncertain ideas.

Gessen writes that Tamerlan thought of joining the Salafist fighters in Dagestan, but was discouraged by his cousin. Back home, talking to Gadzhiev via Skype, Tamerlan “boasted of his growing outspokenness.”

He had twice raised his voice in mosque—in fact, he had twice either staged a walkout or been removed from mosque for objecting to the imam’s acknowledgement of non-Muslim holidays…. Gadzhiev reacted with his familiar mix of approval and condescension: Tamerlan was still acting like a big baby—speaking up against the imam in mosque is not a done thing—but on the other hand, his heart was clearly in the right place, even if his intention was still muddled.

In Dagestan, Tamerlan was accepted and offered a sense of meaning. The influential person he bonded with had strong views about American and Russian treatment of Muslims, and Tamerlan tried to adopt that identity. “Why can’t you believe that he simply objected to U.S. foreign policy and that’s why he did it?” Gadzhiev asks Gessen. Tamerlan’s views about Islam and the U.S. were confused and superficial, but bombers do not need to be sophisticated. When Tamerlan attacked the marathon, perhaps he was also showing off for his friend.

“The imagination demands something distinct, huge, and immediately recognizable to explain the leap between and ordinary life and the path of a terrorist,” Gessen writes. If the absence of something distinct, huge, and immediately recognizable at the heart of the Boston Marathon bombing feels implausible, consider this New York Times article, published just last Sunday, titled “A Norway Town and Its Pipeline to Jihad in Syria.” “Why is it,” the article asks, “that certain towns, and even small areas within them, generate a disproportionate number of jihadists? The reporter, Andrew Higgins, offers a pretty good answer a third of the way through:

In interviews … officials described an unsettling and relatively sudden turn for a clutch of youths, apparently impressed by the example of a popular local soccer player, Abdullah Chaib. Beneath an alluring image as a personable and handsome local hero, he harbored a deep commitment to jihad and was among the first to go.

The Norwegians who went to Syria were young, impressionable, and a little bit aimless. Someone cooler than them decided to go to war. They followed.

The Brothers is certainly among the best journalism produced about the bombings, which is why it is unfortunate that it is marred by a bizarre conspiracy theory near the book’s conclusion. Gessen suggests that Tamerlan was recruited as an informant for the FBI in 2011, protected by the agency when he committed three murders later that fall, perhaps at the behest of the Watertown police department, and then aided in developing the bombing plot.

Such a theory is delicious and at least plausible—of the several hundred federal terrorism cases prosecuted since 2001, all but four have involved FBI informants or agents acting as instigators. “The history of terrorism is full of recruits gone rogue—it is dominated by groups that switched or abandoned loyalties,” Gessen writes. “Perhaps the only surprising aspect of the FBI’s list of manufactured terrorist plots of the past dozen years is that all of them appear to have remained in the agency’s hands.” Both bombs were somewhat more advanced than was originally reported. And Tamerlan may have been involved in the deaths of the three men in Waltham, which were not thoroughly investigated at the time. Gessen also finds curious the presence, reported by Cambridge police officers, of several undercover FBI agents in the city well before the agency identified the brothers.

But after two years spent researching the Tsarnaevs and the FBI, is seems more likely that Gessen herself was just unable to believe that they acted alone. Her theory is supported by conjecture and circumstantial details, but not documentation or direct reporting. (At least, none that is visible in the book, which does not include notes on sourcing.) The theory is hard to take seriously.

“Perhaps it is just too frightening for most people to believe that a small group—or just a pair—of ordinary people using means most of us could have at our disposal and following a plan that spanned barely an afternoon could inflict so much pain and suffering on so many,” Gessen writes. That is frightening, but after reading The Brothers, it is not hard to believe.