As California’s “rainy” season comes to an end and Governor Jerry Brown introduces the drought plagued state’s first mandatory water restrictions, it’s now becoming more important than ever to find a sustainable alternative water source. Desalination—the energy intensive act of stripping sea water of its salt content—has been the much-discussed solution. There exists, however, another process: recycled wastewater. Though understandably unappealing on the surface, recycling wastewater is perhaps California’s best option.

Here’s what you need to know:

WHAT IS RECYCLED WASTEWATER?

Recycling wastewater is, generally speaking, the process of re-purposing or re-using once-dirty water. Most commonly, recycled wastewater refers to treated sewage water, which can be used for both irrigation and consumption. It is called many different things—re-claiming, water recycling, and sometimes “toilet to tap.” The size and scale of recycling wastewater can vary dramatically, from the on-site home facility that collects and re-uses laundry water for irrigation purposes, to a massive city-operated plant that filters and purifies sewage to re-supply depleted aquifers.

WHERE IS RECYCLED WASTEWATER USED NOW?

As over 30 percent of the United States is undergoing a moderate to extreme drought, states like California, Texas, Florida, and Oklahoma have already implemented recycled wastewater practices.

Currently, irrigation is the most common use of recycled wastewater; lawns, golf courses, parks, and schoolyards all used reclaimed water for irrigation. (Delaware has been using recycled wastewater to irrigate crops since the 1970s, according to Pew.) Reclaimed water can also be used to fight fires and help replenish natural wetlands.

In California, Los Angeles’ Tillman Water Reclamation Plant recycles six million gallons of water per day, but none that is yet used for drinking. Earlier this week, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti revealed the city’s first ever sustainability plan, which he promised would “expand recycled water production by at least six million gallons per day” by 2017, and “expand recycled [drinking] water production, treatment, and distribution.”

Neighboring Orange Country, on the other hand, has for decades used its Groundwater Replenishment System to restore low levels of groundwater—its drinking water. Orange County is one of the few counties in the U.S. that currently drinks its recycled wastewater.

WHAT IS THE PROCESS OF RECYCLING WASTEWATER?

To get the sewage irrigation-ready, it must undergo a basic treatment procedure: After letting the solids naturally separate from the liquid (the solids can later be used as a fertilizer), the water is filtered, cleaned, and put into purple pipes—which are indeed underground purple pipes that keep this recycled water separate from the normal water supply.

In order to get the water to a drinkable quality, it needs to go through several more stages of purification, called advanced treatment. After going through a reverse osmosis filter, the water sits under a UV light, which, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, is a very effective way to kill waterborne pathogens and diseases. In Orange County, often lauded as a pioneer in recycled wastewater practices, they then take this advanced treated water and put it back underground. From there, it’s filtered though sand and dirt, and can eventually mix with the existing groundwater.

WHY SHOULD WE USE RECYCLED WASTEWATER?

In the midst of this historic California drought, all means to generate clean water should be considered. But recycled water in particular offers a plethora of advantages, and almost no disadvantages.

While there are an admittedly limited number of studies on the topic, there have been no documented cases of reclaimed water causing any sort of disease or sickness, according to Pew.

Recycling wastewater could decrease, if not eliminate, Southern California’s dependence of imported water from the Colorado River and the Sierras, and could also work to keep its aquifers full. Groundwater, the Department of Water Resources estimates, provides California with close to 60 percent of its water during a dry year. In coastal settings like California, an additional concern about a depleted groundwater supply is the intrusion of saltwater, which flows in to fill the aquifer’s empty space.

Perhaps most importantly, though, recycled wastewater is nearly universally agreed upon as a better option than the other much-discussed alternative to a depleted water supply: desalination.

HOW MUCH BETTER IS RECYCLED WASTEWATER THAN DESALINATION?

Recycling wastewater is far better than desalination, according to Conner Everts, facilitator at the Environmental Water Caucus. After decades of working on issues relating to California’s water at the county, city, and state level, he says recycling wastewater is a fraction of desalination’s cost and actually has environmental benefits.

“Recycled water produces far more water [than desalination], it’s far more reliable in terms of actual operations, it uses less power, it provides a beneficial use for ground water, it offsets surface water supplies, and it actually prevents discharges into the ocean, as opposed to creating them,” Conner says.

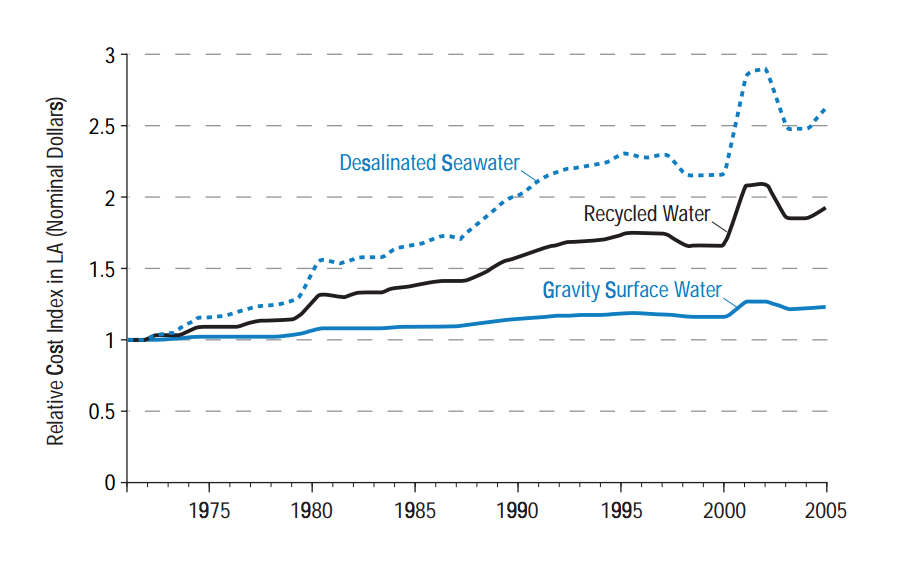

In 2006, the Pacific Institute published the results of a 24-year study on the comparative costs between surface water, recycled water, and desalination. It found that desalination was consistently more expensive than the other two options.

Western Australia, after facing a historic drought throughout the 2000s, began using both desalination and wastewater recycling plants. The government of Western Australia noted in 2013 that “[reclaimed water] was less expensive than a desalination plant, and used about half the energy of a desalination plant.” The city of Perth now uses seven billion liters of recycled wastewater every year, which accounts for 20 percent of its drinking water. (Also of note: All 62,300 of its reclaimed water quality samples “met strict health and environmental guidelines.”)

BUT IT’S GROSS!

Despite all of its positives, drinking water that was at one point sewage leaves most of us with understandable apprehension. Researchers call this the “the yuck factor.” Before Perth’s highly successful implementation of reclaimed water—which has garnered a 76 percent approval rating—citizens of Queensland’s Toowoomba successfully defeated a recycling wastewater proposal in 2006—even though local dam levels were at 20 percent capacity. Getting citizens to not only accept, but embrace reclaimed water is a bit tricky, but Everts thinks that once the shock factor dissipates, most are willing to give it a shot.

“For years in Orange County we had a don’t ask, don’t tell policy,” he says. “But eventually we just came out and said this is sewer water but it’s clean, and we found that people were pretty welcoming. They didn’t care.”

Of course, all drinking water is recycled in some form. As the aforementioned Pew article points out, “all water loops continuously through use and reuse, whether it happens naturally through the hydrologic cycle or it is intentionally captured and reused.” For example, unused recycled water in Dallas is put into the Trinity River, which makes its way downstream into Houston’s water supply.

Recycled wastewater is California’s best bet. So what’s the big stink?

Lead photo: Wastewater treatment. (Photo: gameanna/Shutterstock)