Earlier this month, when the student government at the University of California-Irvine banned the American flag—and all flags—on a part of the campus, the national media pounced, Internet trolls snarled, and lawmakers swooped in with a proposed amendment to outlaw the ban.

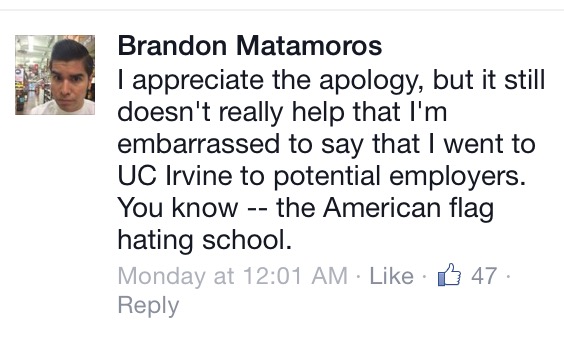

Even after the ban was reversed and student leaders apologized, the Internet hand wringing persisted. Students at the school took to Facebook, worried that the brouhaha would brand the school as un-American and sully their career prospects.

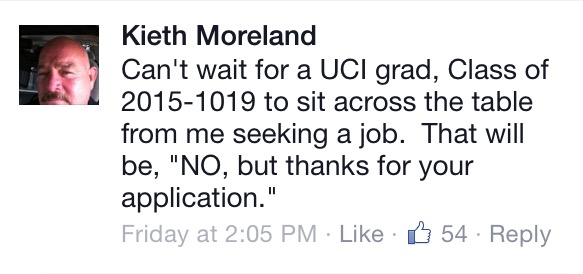

Meanwhile, comments on a student-run Facebook page suggested that students’ fears weren’t unfounded.

This may be the Internet age, but even the Bard understood the currency of a good reputation when he wrote in Othello, “But he that filches from me my good name, robs me of that which not enriches him, and makes me poor indeed.” Today, every gaffe—and worse—is instantly consumed by millions of eyeballs—and employers.

Indeed, after the child sex scandal erupted at Penn State, the university career services center sent a somewhat misguided letter of advice to students, as Gawker reported:

Students may acknowledge that they are primarily concerned for the victims and also concerned for Penn State in these unsettling times. However, students should keep the focus on the job or internship for which they are applying and how they will excel in the opportunity. Students should note that they can only take personal responsibility for their individual actions. Talk about all of the good work accomplished at Penn State in building the skills and professional qualities in preparation for the position, and about the excitement to put those skills to work for the employer. Inform the employer or internship site that, if hired, you will reflect favorably on the employer through your good work, core values and skills obtained through our University.

In recent years, this online judge and jury has given rise to an entire reputation management industry. And it’s raised this question: Can ties, even tenuous ones, to a tarnished organization or group really dim your job prospects?

Researchers, as it turns out, have given this somewhat sweeping brand of guilt-by-association an official term: demographic stigma. It’s the “stigma of belonging to a discredited social category such as an industry (e.g., the tobacco industry) or organization (e.g., innocent employee of Enron),” Danielle E. Warren explains in a paper titled “Corporate Scandals and Spoiled Identities.”

The stigma can be near inescapable, as former employees of Enron attested in 2014, more than a decade after the energy giant collapsed amid executive fraud. The Associated Press reported that the former employees remained “upset that many people still think the vast majority of Enron workers were part of the greed and dishonesty” that led to the company’s demise.

“Enron wasn’t evil…. A few individuals were corrupt, but not the entire company,” Karen Hunter, one of thousands of Enron employees who lost jobs, told the AP.

Enron’s lasting taint piqued the interest of Stanford University psychology researcher Takuya Sawaoka. “These were people who did nothing wrong themselves but suffered reputational damage merely by being associated with a fraudulent employer or company,” Sawaoka said in a press release about his paper.

In a study published recently in Social Psychological and Personality Science, Sawaoka and co-author Benoît Monin found that the taint of an unethical company can dim the career prospects of the innocent.

After allowing subjects to read a series of case descriptions meant to mimic real-life dilemmas, the researchers discovered that subjects still harbored negative perceptions of characters who hadn’t worked directly with transgressors but were tied to the same company. In one of the simulations, researchers described a fictional employee, “Brett,” who had been charged with corporate fraud. They asked study participants whether they’d recommend hiring “Luke,” who wasn’t involved in the wrongdoing but worked at the same firm as Brett. They found that Luke, though innocent, was viewed negatively—and was less likely to be hired.

Sawaoka, the paper’s lead author, described this effect as “moral spillover,” meaning that the actions of a single transgressor stained the group, in this case, a company. And the spillover effect remained, regardless of the severity of the wrongdoer’s shenanigans—whether it was a self-serving lie like inflating one’s own performance to land a heftier bonus, or a company-serving lie, like deceiving a customer. And when the culprit was high up in the organization, the authors discovered that this “moral spillover effect” was amplified and the wrongdoer’s colleagues were viewed even more negatively—and were less likely to be hired.

Sawaoka suggested that spillover effect might be muted by downplaying the wrongdoer’s status in the institution and emphasizing the ways in which the misdeeds are personal flaws and unrepresentative of the organization.

Warren, who studies business ethics and management at Rutgers University, also says the stigma’s longevity hinges on the extent to which an individual is perceived as being “in control.” In the case of the college students worried about the flag ban, she says, “I would think that the extent or length of the stigma associated with being a student at a university with an unpopular rule would depend upon how much the public views the students as being in control or a part of the university’s rule-making process.”

The near-ubiquity of bad news might also work in students favor, says Larry Smith, who has guided major corporations and universities through crisis for 20 years. “There’s this desire to tune anything out that doesn’t affect me, or my job or my family,” he says.

Warren notes that students might curb any negative effects by emphasizing their powerlessness in the policy’s adoption. A perception of powerless, Warren says, has been shown to lessen stigma. For example, a study of individuals with AIDS published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology found that the stigma surrounding the ailment lessened after the public understood that it could be transmitted by involuntary means like blood transfusions.

The students might also take heart in our country’s seemingly boundless belief in second chances. A study in Social Science Quarterly of scandal-ridden politicians showed that only about a quarter ultimately exited office, and that two-thirds of those who sought re-election won.

Even so, Sawaoka, whose study underscored the strength of guilt-by-association, suggested today’s fishbowl society requires individuals to carefully evaluate the company they keep.

“It may not be enough to be ethical yourself,” he said.