Earlier this month, Tinder launched “Tinder Plus,” a paid subscription version of the dating app that includes bonus features like a “rewind” button for saving accidental rejections and a “passport” to scope out users based anywhere in the world. Its cost is determined by what Tinder calls “differentiated price tiers by age”: Users pay $9.99 per month if they’re younger than 30; $19.99 if they’re older. Not surprisingly, this pricing system has really pissed some people off. Tinder justifies the difference by claiming it has tests showing younger people are “more budget constrained.” But critics have fired back with a much less generous implication: Old people are desperate.

“Tinder has, with the foresight of an evil genius, identified the age at which you start to wonder whether you might be single forever—or at least when parental queries about your relationship status start to become quite panicked,” writes Daisy Buchanan, author of a book on online dating (and not, I should point out, the character from The Great Gatsby). “Making it more expensive for ‘older’ customers makes them feel as though they’re less desirable, which is no way to help a single person to feel confident about their prospects.”

The extent of this anger over Tinder’s apparent ageism seems a little shocking at first, especially given the company’s less-than-perfect reputation for political correctness. There are plenty of other online dating options out there, after all, and Tinder’s non-premium version—which, by one estimate, boasts around 50 million monthly users—is still totally free. But since its launch in 2012, Tinder has become a beacon of sorts for the very future of human connection—a first-of-its-kind tool that is steadily growing beyond hook-up culture to link people of all varieties, from friends to roommates to Boston snow shovelers. As a result, the dated values this new “age tax” suggests seem to have struck a particularly offensive chord. It’s like hearing a new friend drop a racist joke.

Beneath self-righteous indignation, there’s also the fear that Tinder Plus’ prices aren’t just cold-hearted—they’re accurate.

But what if this is about more than ageism? Beneath self-righteous indignation, there’s also the fear that Tinder Plus’ prices aren’t just cold-hearted—they’re accurate. The company refused to comment on the specifics of its research for this article, but if we believe that their tests do in fact show the new prices “were adopted very well by certain age demographics,” then we face a grim reality: Yeah, maybe dating for over-30s does kind of suck.

There’s quite a bit of research to suggest as much. As unmarried people age, their dating pools shrink, according to studies. One report shows they have fewer sexual partners, even though other studies suggest sexual desire often stays strong later in life (just not at a youthful peak). Unsurprisingly, women have it worse than men: Surveys show men “consistently dislike older women,” which may be a doubly cruel bias because some research also suggests women hit a sexual peak from late 20s to mid-40s, right after what’s conventionally looked at as their most datable years. (Of course, what even constitutes a sexual peak is often debated.)

Unmarried women and men both have to put up with the social stigma of being alone—something University of California-Santa Barbara psychologist Bella DePaulo calls “singlism.” “There are all sorts of ways in which people think that if you’re single you just aren’t as good as someone who’s married or even seriously coupled,” DePaulo says. “They just assume you’re not as happy, you’re lonely, you’re self-centered, you’re not fully adult. How could you possibly be the full, complete, joyful person leading a meaningful life that married people are?”

According to DePaulo’s research, people are more apt to pity a hypothetical man or woman who’s single, even when that person is compared alongside another hypothetical person who’s married but otherwise described in the exact same way. And pity only grows worse as single people get older. In DePaulo’s words: “The perception, the stereotype, is ‘Oh, you poor single person, you are even more miserable when you become 40.'”

Thankfully, there’s good reason to believe things are looking up for daters in and beyond their 30s. For one, DePaulo says the lonely old single person stereotype is flat-out wrong. For people who are OK with being single, at least, her studies suggests the older single people get, the stronger, wiser, and more of a “complete, secure, happy person” they become. And for those over-30s who are not content to be alone for the rest of their lives, there are more people to date than ever. For the first time in the country’s history, there are more single American adults than married ones.

The more we rely on Tinder for connection, the more it becomes a gatekeeper to our social lives—and to all those romantic options the future seems to promise.

There are also more ways for all these single people to meet each other—especially, yes, for people above 30. “Online dating is particularly alluring because it provides an alternative to meeting dates in bars or through friends,” says Summer McWilliams, a sociologist at University of South Carolina-Beaufort who studies dating in middle and later life. “Middle aged and older adults feel out of place frequenting singles’ bars filled with younger people and run into issues dating within their social circles, which include prior spouses’ or partners’ friends.”

McWilliams’ enthusiasm is common among researchers who study dating and aging. Osmo Kontula, a Finnish sociologist and the director of The Society for the Scientific Study of Sexuality—and something of a rock star in the sex research world—lauds dating sites for decreasing solitude, making it easier for divorcées to find new love, and even boosting the social acceptability of mid-life singlehood. “Online dating has now changed dating a bit like a game and as a part of a more exciting social life,” he says.

These new benefits are extensions of larger cultural shifts in recent decades, which appear to be loosening long-standing dating conventions for young and old daters alike. While there’s a long history of studies showing men tend to seek attractive women and women tend to seek wealthy men, recent evidence suggests gendered standards of attraction break down in nations where women and men see each other as equals. Racial, religious, and age divides appear to be following a similar pattern.

It may not be that Tinder’s ageist, but rather that the company is now confident enough to come off as ageist in pursuit of the highest profit.

These changes mean there are fewer dating taboos, more people who are single, and more ways for single people to find each other. And that means more dating. Maybe even, as DePaulo sees it, more freedom. “What’s really happening is we all have more options,” she says. “If you’re over 50 and you want to date, you can hop online and try to find someone that way. But I’d also like to think that if you’re over 50 or any age and you don’t want to do that, you also feel freer to live the kind of life that you want.”

That’s not to say freedom comes without a cost. Tinder Plus’ prices, in fact, may be the perfect example of why DePaulo’s vision should only be embraced with caution. The dating scene she describes puts Tinder, or any popular social networking site, in a powerful position. The more we rely on it for connection, the more it becomes a gatekeeper to our social lives—and to all those romantic options the future seems to promise.

If there’s anything the new prices show us, it may not be that Tinder’s ageist, but rather that the company is now confident enough to come off as ageist in pursuit of the highest profit. If its tests turn out to be correct, and everyone expected to buy in does, we may find ourselves having to pay for access to each other more and more frequently.

Either way, dating past 30 should be easier in the future. Fingers crossed everyone can afford it.

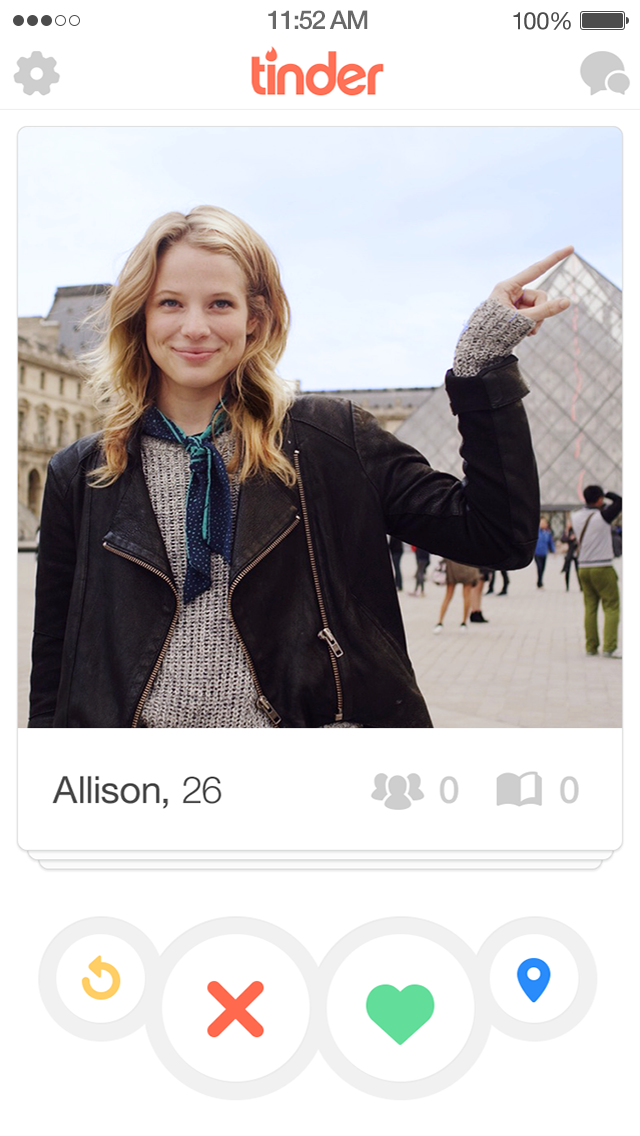

Lead photo: (Photo: Chuckstock/Shutterstock)