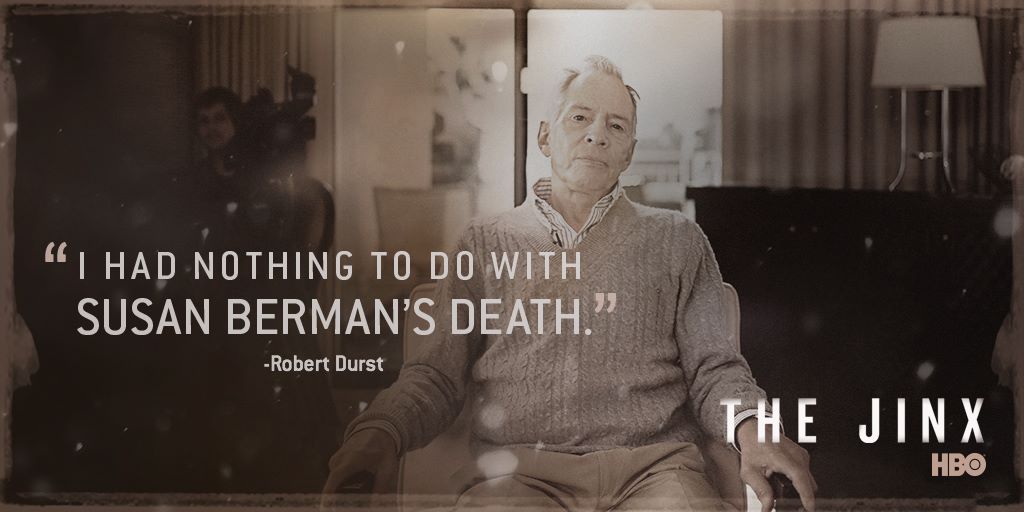

This past Sunday, HBO’s six-part documentary series The Jinx, which re-investigated the three murders that New York real estate millionaire Robert Durst had been suspected of, came to a dramatic conclusion. Without giving anything away—although it’s well-known at this point—the show delivered an ending so unbelievable, so hauntingly picture perfect, that it would have surely been met with laughs and eye rolls had it been written into a work of fiction.

The Jinx built off the momentum established by Serial, last year’s episodic true crime podcast from NPR’s Sarah Koenig. While its ending was decidedly less climactic, Serial’s tale of a true crime and the ambiguities surrounding its initial investigation gripped the culture. (As of February 2015, it had been downloaded more than 68 million times.) These two hits breathed new life into true crime, a genre that has traditionally been viewed as sensational, if not unethical.

Michael Arntfield was a police officer and detective for 15 years before he got his Ph.D. in digital media with a focus on technological crime. Now, as a professor of forensic writing and investigative reporting at Western University in Ontario, and the founder of the Cold Case Society, a criminological think tank that he describes as “a RAND Institute for murder,” he has become a leading voice in true crime. (He also hosts Canada’s To Catch a Killer and is the author of several books.)

We chatted with Arntfield to get a better sense of the history of true crime, what this renaissance means for the genre, and whether The Jinx’s finale sets a dangerous precedent.

You’ve studied true crime and its various forms throughout history. What do you think of the recent legitimization, so to speak, of the genre with Serial and HBO’s The Jinx.

It’s interesting you call this a legitimization. These things go in cycles. I call it a zeitgeist, a new and prevailing ethos that’s really driving the way narratives are told. [True crime] has gone through various stages over the years. Some are done well, some are done not so well.

For whatever reason, Serial really marked a sea change. It is different because its serialized, and I think that reflects the way people are consuming media generally. Between Netflix and HBO, the most critically acclaimed series seem to employ these long narrative arcs and these serialized formats, as opposed to these episodic, cleanly packaged, Law and Order procedural formats that a lot of people are used to. I think Serial re-booted for a new generation some familiar themes and capitalized on those long arcs in that serialized format.

What do you mean by familiar themes?

Well, I listened to Serial at the behest of many, many students of mine, and I was distinctly underwhelmed. I’m not sure what about it appealed so broadly to early 20-somethings. All I could really think of is this is a generation that should have a collective memory at earlier attempts at true crime. But the generation now turns over every two to three years, and prerequisite knowledge sort of expires after a few years. You have the opportunity to recycle tropes and make them new and fresh again. I think we’re seeing that now with true crime—the tide washing over in a generational context. We’re seeing the same storytelling formats are coming back.

In Serial and The Jinx, the journalists were involved in a very recent case where suspects, family members, and investigators are alive, if not part of an active investigation. Do you worry about the journalist affecting the legal process?

I’ve always been a huge advocate for both investigative journalists and civilian subject matter experts really picking up the mantel on these cases that are otherwise not seeing any action. I run a cold case think-tank and I’ve got an A&E show in Canada, but they share the same idea: We take a case, we re-activate it, and run through it with civilian subject matter experts based on open-source information, or information gleamed from informants or confidants or whistle blowers, and bring new technologies and new techniques to bear on them and see what headway we can make.

A lot of people found the shoulder shrugging ending of Serial frustrating. But it’s not always about the final shot of someone being released from prison or the bad guy getting locked in cuffs. If you can get people involved and get them questioning things and holding the justice system officials accountable, even if that’s corroborating what they’ve done, then that’s a good thing. In the Serial case we may very well see an appeal that says everything was done properly. No murder case is perfect. But, if in the end, it turns out that everything was done above board, then great. At least now we know.

The Jinx’s ending was the antithesis to Serial, and viewers really responded to it. In its wake, do you worry about the journalists—filmmakers, podcasters—feeling a need or an obligation to entertain their audience, to provide a satisfying ending? If true crime becomes Hollywood-ized, do you think we’ll start to see a blurring of fact and fiction?

True crime goes through various permutations, but over the years it has been derided as down market, or unethical, because it plays fast and loose often with the ethics of re-opening these cases. It sensationalizes these cases, or examines them through a very salacious lens that’s often insensitive to the victims and the stakeholders. But I think the measure of quality now is perhaps authenticity. We’re dealing with more critical consumers. Things can be fact-checked.

The question will be: Can this renaissance of true crime that we’re in the incipient of right now, can it, for a much more discerning and critical audience that’s out there now, take the high road? The Jinx seems to be serving a remarkable public interest in a very shrewd fashion. Can the genre sustain this? Can they really sustain true crime as an advocacy medium? The success and the legitimacy of the medium hinges on being able to stay within this framework of advocacy ahead of strictly sensationalism or profitability.

Do you think the future of true crime will look more like advocacy journalism?

I hope so. That’s what I’ve always tried to do with it, and why I’ve always advocated for its being in the right hands—because when it is, I think it’s among the most powerful storytelling devices and genres. These visceral stories galvanize people who have various political and socioeconomic backgrounds. So why not, if you can really have your viewers and listeners close ranks like that and find common interest, use it for some altruistic purpose, rather than just telling a story and creating entertainment?

That’s the other thing that interests people about Serial in particular: it’s not a big budget production. This was a grassroots production made by people who were earnestly interested in finding the truth, as opposed to creating a Dateline special. It ended how it ended—without them trying to artificially engineer a Hollywood ending, and that’s the way a lot of real cases end.

Do you see any inherent differences between true-crime stories as told through each medium? The podcast, the feature-length documentary, the fragmented episodic documentary, or the individual television episode?

You must ask: How does the medium shape the message? How does the medium contour or nuance the story, and by extension determine success or credibility? Certainly, one of Serial’s advantages was the fact that the podcast is sort of still this very customized sort of way to consume media. It’s so personalized. I really think we’re seeing this post-network world where there’s no longer appointment viewing and all tastes are customized and all watching or listening experiences are highly customized. I don’t think there’s a secret recipe in any medium to ensure success. I think you’re just seeing the ability for producers to single out real niche markets who have an appreciation for good, factual storytelling.