Note on terminology: Where possible, I use the term LP (little person), as it is the most often preferred term for someone with dwarfism in the United States. I also use the term dwarf, which is the accepted medical term.

When researchers from the biopharmaceutical company BioMarin told representatives of the Little People of America about the results of a drug that could potentially cure one of the causes of dwarfism, they expected a better response than the silence they were treated to. This caught the BioMarin folks off guard. “I think they wanted us to be happy,” says Leah Smith, LPA’s director of public relations. “But really, people like me are endangered and now, they want to make me extinct. How can I be happy?”

BioMarin isn’t the only company trying to eliminate dwarfism. For years doctors have been using limb lengthening and hormone treatments to counter and cure the over 400 underlying causes of dwarfism. And yet, despite these efforts to eliminate what many people see as a disability, society can’t stop staring. From The Lord of the Rings to Peter Dinklage in Game of Thrones, people have long been mesmerized by depictions of LPs. As Smith explains, “It doesn’t matter how normal I am, it’s hard for people to look at me an see anything besides Leah the LP.”

Dr. Judith Hall, a clinical geneticist whose work focuses on short-limbed dwarfism, explains that our staring and our desire to cure are intimately connected. “In the same way that ancient societies viewed those people with differences as a pathway to the divine,” Hall says, “I see them as a pathway to access the knowledge of nature. There is so much to be learned about humans and our genetic make-up by studying the genetics of people with short stature and anyone with a ‘disability’ although I hate that term, don’t you?”

But understanding our curiosity and desire to cure requires an understanding of the history of dwarfism, which lies in the nebulous intersection of medicine and myth.

For much of early history, LPs were considered to be intimately connected to the divine. In fact, pre-literate societies often saw all people with disabilities as conduits to heaven. The ancient Egyptians associated dwarfs with Bes, the god of home, family, and childbirth; and Ptah, the god of the Earth’s essential elements. (Both gods—representing youth and the Earth—play a role in enduring myths and stereotypes, like the fairy tales that claim that dwarfs live underground, or the stereotype about the childish nature of people with short stature.) Because of their connection with the gods, dwarfs were often revered in Egypt, and were allowed to serve high roles in the government.

Whereas dwarfs in the Old Kingdom of Egypt (2575-2134 B.C.E.) were often jewelers, linen attendants, bird catchers, and pilots of boats—all positions of high-esteem, by the Middle Kingdom dwarfs were more likely to be personal attendants or nurses. These positions, while still respected, were comparatively lower status. Historians surmise that dwarfs were relegated to these roles because their short limbs made them perfect midwives and the association with the god Bes. Of course, even in this age of reverence, dwarfs lived lives of bondage.

In ancient Rome, the attitude toward dwarfs was less reverential. Owners would intentionally malnourish their slaves so they would sell for a higher price. In ancient Greece, dwarfs were associated in a menacing and lurid way with the rituals of the Dyonisian cult; art from that period shows them as bald men with out-sized penises lusting after averaged-sized women. This same pattern of reverence and bondage also appears in China and West Africa, where LPs were so often servants of the king. A 17th-century author wrote that the Yoruba people in West Africa believed dwarfs to be “uncanny in some rather undefined way, having form similar to certain potent spirits who carry out the will of the gods.” And out of a similar reverence for their stature, the courts of China employed dwarfs as entertainers and court jesters. Here there also may have been a level of fetishism; Emperor Hsuan-Tsung kept dwarf slaves in the harem he called the Resting Palace for Desirable Monsters.

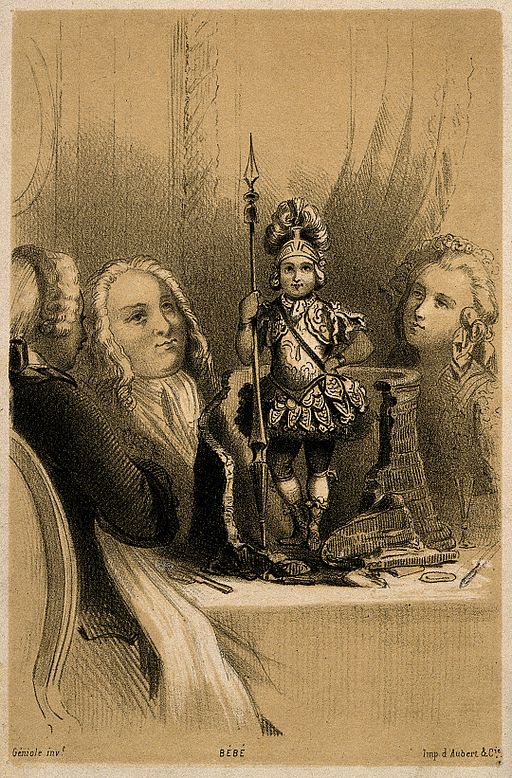

By the time of the Italian Renaissance, LPs had become a court commodity all over Western Europe, Russia, and China. There are tragic tales of court dwarfs and their wild antics. Jan Bondeson writes in The Two-Headed Boy about Nicolas Ferry, the infamous court dwarf of King Sanislas Leszynski of Poland. Ferry was given to King Sanislas when he was about five years old. The King promised his father he would be given the best education and medical care. Ferry’s father didn’t even consult his wife, who had to journey to the court to say goodbye to her son. Ferry, who may have also had learning disabilities, was spoiled and terrorized the court with his antics—kicking the shins of servants and crawling up the skirts of ladies. He even threw a dog out of the window when he believed the Queen loved the dog more than him.

Another Italian, Isabella d’Este, marchioness of Mantua, viewed dwarfs as collectable items. She hoarded them in her vast palace along with art, classical writings, gold, and silver. She also tried to breed dwarfs and kept them in a series of specially designed rooms, with low ceilings and staircases to scale. This was more for their display than comfort. One of Isabella’s dwarfs was “Crazy Catherine,” an alcoholic who stole from her mistress and whose misdeeds were laughed off as entertainment. The history of courts throughout Europe and Russia tell similar tales of dwarfs employed as jesters, or little more than pets—laughed at, loved, and never fully allowed to be human.

As the age of monarchy ended, the era of medicine and medical curiosity arose to fill its place, often providing more opportunities for LPs. Dwarfs were put on display—by others or themselves—for money. In a time where very few occupations were open to LPs, putting yourself on display in a freak show was at least a way to make a living. While traveling around provided LPs with more independence, it also opened them up to the gaping and insensitive curiosity of the public and medical professionals.

It shouldn’t come as much of a surprise, then, to say that LPs were subsequently taken advantage of by greedy brokers and agents. In his book Freak Show, Robert Bogdan explains the phenomena of human exhibits, singling out the insular nature of communities as a leading cause. Animals and humans that were outside of the norm were exciting curiosities; different races, ethnicities, and disabilities were all billed as novel entertainment. Bogdan quotes a handbill advertising a Carolina dwarf in 1738 who was “taken in a wood in Guinea; tis a female about four foot high, in every part like a human excepting her head which nearly resembles an ape.”

For most of early history, the response of doctors to LPs was to measure everything—nose, hair, genitals. This meaningless collection of data is often accompanied by condescending notes on the appearance and intellect of the dwarf.

From these human exhibits came the growth of dime museums, midget villages, and Lilliputian touring communities, where many LPs rose to prominence. But while these exhibitions took center stage, several LPs made incredible, albeit quieter, contributions to history. There were people like Antoine Godeau, a poet and bishop best known for his works of criticism, or economist Ferdinando Galiani, one of the leading figures in the Enlightenment. Then there’s Alexander Pope, a classical poet known as the “most accomplished verse satirist in English.” Plus Benjamin Lay, an early abolitionist and good friend of Benjamin Franklin. And Novelist Paul Leicester Ford, artist Henry de Toulous Lautrec, electrical engineer Charles Proteus Steinmetz. The list goes on.

Yet even in this time, as many LPs grew to prominence, medicine was able to do little more than collect data. Dr. Josef Mengele, the infamous Nazi doctor, kept an LP family of Romanian performers captive in Auschwitz, subjecting them to various tests and experiments that included pulling out teeth and hair specimens. Mengele is remembered as the angel of death—a cruel doctor who performed unscientific and often deadly experiments—yet his data collection on LPs isn’t much different than that of the medical community in centuries prior.

For most of early history, the response of doctors to LPs was to measure everything—nose, hair, genitals. This meaningless collection of data is often accompanied by condescending notes on the appearance and intellect of the dwarf. Even as late as 1983, Mercer’s Orthopaedic Surgery offered this observation about achondroplasia: “Because of their deformed bodies they have strong feelings of inferiority and are emotionally immature and are often vain, boastful, excitable, fond of drink and sometimes lascivious.”

The obsessive data collection reads like a stack of clues, wherein doctors hope to find an answer to the riddle of difference. With nothing else to do, like the Egyptian pharaohs and the courts of kings, doctors found themselves staring too.

In the absence of a cure, most early doctors focused on prevention. They believed that dwarfism was caused by the mother having seen another dwarf or animal. In fact, for most of medical history many disabilities and unexplained deformities were chalked up to maternal impressions. Consequently, pregnant women often sequestered themselves away from their communities, acting like they themselves had a disability.

This isn’t different from the modern approach to “curing” dwarfism. With early genetic testing, many in the LP community are worried about unborn dwarfs being allowed to be born.

In the aftermath of World War II, LPs found more and more opportunities to work outside of entertainment. This was due in part to Billy Barty, a film actor and television star who, in 1957, organized a meeting of LPs in Reno, Nevada. This meeting eventually led to the founding of the Little People of America, a powerful non-profit that advocates for the rights of LPs in America.

The history of dwarfs is a history of subversion, stereotypes, expectation, and survival. It’s the history of how people treat other people who are different.

Before Barty, with the exception of circuses and traveling groups, most LPs were isolated. There was no way to band together to advocate for civil rights. A little more than 30 years after that first meeting in Reno, the Americans with Disabilities Act was passed in the United States, granting LPs more access and freedom than ever before.

The history of dwarfs is a history of subversion, stereotypes, expectation, and survival. It’s the history of how people treat other people who are different. And, while much has changed, very little is different. The tension between curiosity and cure is still prevalent. The popularity of shows like Little People, Big World and The Little Couple, while laudable for their portrayal of normal people with difference, show that we can’t stop looking at LPs. And companies like BioMarin and non-profits like Growing Stronger, which all seek to find a cure, show that we can’t stop trying to change them.

Yet, as a geneticist, Hall dismisses the notion that she is trying to change the LP community. She describes her work as merely offering a choice to individuals. “There are genetic tests for Downs Syndrome, but they haven’t eradicated people with Downs,” Hall says. “In the same way, the work I do and the work of other scientists isn’t to eradicate difference, but rather to offer options for dealing with it. It’s all about offering choices, really.”

But Smith, the LPA’s director of public relations, pushes back. “The world is full of difference.” Smith says, “Sometimes I wish people would look elsewhere.”