I remember exactly how I felt when I visited his apartment for the first time. Upon entering his room, I quickly noticed a pair of women’s jeans casually discarded on the bedroom floor, as if still warm. Then there was the Dave Matthew’s Band poster on the inside of the closet, hiding in plain sight. It was only then—somehow not when he’d invite random girls to hang out with us—that I learned about his feelings on monogamy (and bad taste in music).

A survey of friends on a new lover’s apartment begets similar, eyebrow-raising reflections: stuffed animals, a handgun under the mattress, a noose, a riding crop, and a large collection of dolls dressed as Nazis, just to name a few.

Though these observations would go on to be funny anecdotes, in the moment they felt like important, crucial clues to the real person beneath the second-date veneer. Shouting hobbies across a bar table gives a person some idea of who you are, but it’s nothing compared to seeing them in their natural habitat, surrounded by the things that matter to them most.

“I’m not proud of this, but I kind of assumed he’d had a chaotic, neglectful childhood based on the state of his room.”

As a person amasses objects and curates his or her space, it becomes an extension of self. In a 1980 study, “Importance of the Artifact,” geographer Yi Fu Tuan noted: “Our fragile sense of self needs support, and this we get by having and possessing things, because, to a large degree we are what we possess.” This idea goes as far back as 1890, when philosopher William James noted that “a man’s self is the sum total of all that he CAN call his.”

Susan Clayton, an environmental psychologist who teaches at the College of Wooster, says that we begin to pick up on environmental cues at a very young age, usually around elementary school, when we first become aware that our surroundings elicit “social feedback” and demonstrate “the kind of person we are” to others. Think of a child desiring a particular wall color, or a teen’s desire for a specific, cool band poster.

As we get older, there are also social tropes that become engrained, like the idea that a messy desk is a sign of internal chaos (and maybe even creativity). Or the age-old cliché that a person’s bookshelf is a kind of window into the intellectual soul. There’s that classic bit of John Waters’ advice: “If you go home with somebody, and they don’t have books, don’t fuck ’em!”

But in contemporary dating, it’s more than just what’s on their bookshelf. Observing a person’s belongings can push fast forward on a relationship, and give you a glimpse into someone’s inner life, a life they might not be ready to reveal. For one friend, who found a speculum in her new man’s closet, she learned that he was deep into BDSM long before he got a chance to tell her.

Look no further than popular culture to see the power of the object clue. There’s the obligatory movie scene where a woman is rifling through her lover’s drawers looking for leads, a la Kim Basinger in 9 1/2 weeks. In the early 2000s, the premise was even the basis for a popular reality show on MTV called Room Raiders. Three men or women would have their rooms “raided”—even blacklighted—by a love interest, who would then select their date based on the contents of their space alone.

Of course, reality television displays an unrealistic extreme, but it draws on the truths of my friends in their late 20s and early 30s. Rachel Millman says that after scanning a new lover’s space for safety, she begins examining the room and their possessions to make little connections: “You’re assigning a narrative, and building a story between the two of you.”

“If you go home with somebody, and they don’t have books, don’t fuck ’em!”

When Ryan Britt was single, he would immediately notice a woman’s cleanliness when he went to her apartment for the first time. If she were messier than him, it would leave a bad impression. “I want to be the one who’s shamed into being cleaner, not the other way around.”

Years ago, Nona Willis Aronowitz visited her then-boyfriend’s place for the first time, and was horrified. His room was in complete disarray, littered with a “disturbing” number of Star Wars action figures and empty beer cans. An ashtray full of cigarette butts sat on the nightstand. “What kind of animal smokes in bed?” she remembers thinking. “I’m not proud of this, but I kind of assumed he’d had a chaotic, neglectful childhood based on the state of his room.”

Clayton explains that you can think about this kind of exchange simply as a communication, similar to a verbal one. In the same way that things can be lost in translation, “what we think people are going to interpret isn’t always what they interpret.” For Aronowitz, it turns out she judged too early. Her beau was selling his childhood toys on eBay, and his upbringing was one of suburban perfection. (They are now married.)

So, these snap judgments can be hasty and inaccurate, but even when they’re not—like that of the love-letter-from-someone-else variety—how much do they really matter to someone with a heart full of lust.

The most striking commonality between everyone I talked to wasn’t the “weird” things they observed, but rather how they were willing to overlook them. The stuffed animals would be removed from the bed before sex without a word. The gun would be frightening, but kind of a turn on. And as for the speculum finder: “I should have dumped him then, but I didn’t.”

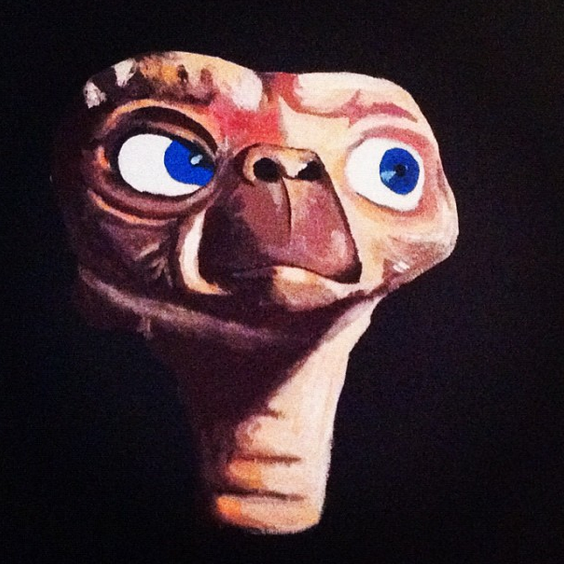

If these things can be dismissed, imagine what can happen when someone’s room actually makes you like them more. I once noticed a hyper-realistic, hand-painted portrait of E.T. on a man’s wall that was bizarre and unique and completely endearing— just like him.

Years later, our rooms would become one, and then sadly two again. But he’d let me keep the E.T. portrait. “I know how much you love it,” he’d say before taking the last of his stuff down to the car.

I’d hang it in the living room of my new place, even though in the first few months just a peripheral glance would make my stomach drop. In time though, it’d become just another decoration amongst a vast collection of trinkets. One day, a new boy would come over, and I’d notice that E.T. caught his eye. I’d watch a familiar sense of wonder flash across his face, and he’d smile and say, “Cool painting.”