A drive from the Bay Area to Los Angeles takes, as far as my car goes, one-and-a-half tanks of gas. This means every trek necessitates one instance where I pull off the I-5 and into a small oasis of commercialism, with several different burger joints and more than a couple different gas stations. Usually, the gas station prices are in the same ballpark. Maybe one’s a few cents higher if it’s the first station off the ramp, or perhaps a station further down is offering a free car wash to lure the less desperate. But every now and then, there’s one station with prices so far above others nearby—and with a full line of cars waiting to pay for that more expensive gas—it makes zero sense to my understanding of the free market.

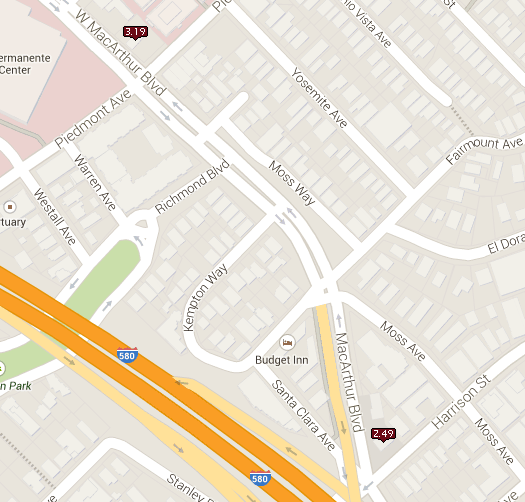

For instance, here are two gas stations in my neighborhood that (1) are less than one mile from each another and (2) have a 70-cent-per-gallon price difference.

While there are certain situations where paying a premium for essentially the same good is beneficial (if not tangible then emotional)—say, paying extra coinage at the corner market rather than going to Walmart—buying gas seems different. Most see it as a necessity rather than a choice, more akin to a bus pass or highway toll. And no one loves buying gas; as more and more damning stats about global warming emerge, the head shake from that angel on our shoulder gets more fierce. What’s going on here?

There are location issues to consider. The $3.19 price is from a Shell station positioned across from the newly opened Kaiser Permanente hospital and adjacent to the ritzy strip of Piedmont Avenue. That’s solid real estate. But that $2.49 price from a Quik Stop? They have a lock on all the traffic coming down the heavily used MacArthur exit off I-580. The price difference between the two stations—even if you were looking through the location-location-location explanatory lens—shouldn’t be 70 cents a gallon. What does Shell have to say about this?

“While the name on the sign reflects the brand of the motor fuel being sold on the premises,” says Shell spokesperson Kimberly Windon, “the convenience store and the day-to-day site operations are the legal responsibility of the wholesaler, site owner, and/or operator who make their own operating decisions including setting gasoline prices as they believe appropriate.”

“You buy Chevron, and they say they put tech-something in there, they put it in all of their advertising. But there’s very little difference between gasolines.”

Just because the brand’s name is on the sign doesn’t mean they have anything to do with the pricing. Taking the next logical step to an answer, I called the above-mentioned stations, but they both refused comment. When I called another 10 or so gas stations in the area, I was just as quickly jettisoned off the line. (“I don’t have time for this,” was how one owner put it, which captured the general sentiment from the others.) Finally, I reached one owner who agreed to speak to me, albeit anonymously. These people are a suspicious bunch, it turns out.

“On top of the [gasoline] purchase price, there are a whole bunch of fees added,” the Chevron owner says. “California lead poisoning fee, federal oil recovery fee, then a cleaning fee. All these things get tacked to that price.” There are also costs related to keeping the store clean, workman’s compensation, payroll taxes, and pump maintenance. “That’s horrendous because not anybody can work on it. It has to be a licensed guy, and they are very expensive to work with.”

These costs affect the entirety of the industry, though; a rising tide lifts all boats. Maybe one station pays their workers a little more, or has to pay off that new car wash it just installed. But it’s not buying cheaper barrels of oil. Rather, to pinpoint where more substantial differences come in, you have to look at how a consumer pays.

For example, Arco consistently provides the cheapest gasoline prices largely because it doesn’t allow customers the option to pay with debit/credit cards. This means the company doesn’t have to fork over the fee associated with each purchase (anywhere from two to seven percent). Instead, to keep its prices low, it allows customers to pay with cash, or to use their own credit/debit machines for a 35 cents or so per transaction. Arco customers are paying the fee; everywhere else, the station does. (It’s not unlike the business model of Spirit Airlines, which consistently shows up as the lowest cost in comparison searches because its prices don’t include “frills” like complementary beverages, Wi-Fi, or baggage.)

“Independents can bargain with the credit card company and get a better deal than the brand names,” the Chevron owner says. This is, most likely, how Quik Stop can offer a low price compared to Shell. But beyond the subtle differences (the cost of maintaining a clean environment) and those inherent to the business model (negotiating lower credit card fees), there’s something else stations take into consideration when coming up with their price: the quality of the gas itself.

“Chevron, in my opinion, has the best gas,” the Chevron owner says. “I’ve tried it on different cars, and it truly has quality gas.”

But, well, does it really?

Not according to Daniel Sperling, a civil engineering professor at the University of California-Davis. “You buy Chevron, and they say they put tech-something in there, they put it in all of their advertising. But there’s very little difference between gasolines,” he says. “There can’t be too much difference, because at the fundamental [level] gasoline is the same.”

If you’re paying nearly a dollar a gallon more for “additives,” well, they better have bathrooms with gold-plated bidets.

See, all gas comes from the same place: out of the ground as crude oil, through the common carrier pipelines, into the refinery, out via tankers or more pipelines to the station. This means the actual gas sold at any station is the same basic stuff as the one next door. Rather, the differences in gasolines are in the so-called “additives” each brand puts into them at the refinery stage.

Just what are these additives? Chevron adds something called Techron to their gasoline, which it claims leads to a cleaner engine, better performance, and maximum fuel economy. Shell utilizes a “patented and exclusive” Nitrogen Enriched Cleaning System, which comes with the same promises of fuel economy and engine-cleansing. Arco stops short of a patented name, simply telling customers that their fuel’s so good that consumers don’t need to supplement with over-the-counter additives.

But is there any proof these additives do anything? Not really. Consumer Reports tackled a version of this question back in 2012, writing that paying for premium gas may be a “waste of money”:

Engines requiring premium gas are typically the more powerful ones found in sports and luxury vehicles, which are more vulnerable to knocking, so recommended fuels have octane ratings of 91 or higher. Using premium gas in an engine designed to run on regular doesn’t improve performance.

Many sports or luxury vehicles get along just fine with regular gasoline as well, they wrote. If the owner’s manual says premium gas is required, go ahead and splurge. If it’s only recommended, ordinary gas is fine. If you’re buying gas from a company that’s registered as “top tier”—which includes all the big brands—it’s the same stuff. (It should be noted that Click and Clack agreed.)

In the end, then, the decision to buy more expensive gas can be broken into normal reasoning (repetition; if you have a good relationship with the owner) and the usual brand vs. generic battle (the “patented difference” that slick advertising tricks consumers into believing). If that slightly more expensive station is the one on your route, or if you like the smell of their window washing fluid, a few extra pennies per gallon may be worth it for you. But if you’re paying nearly a dollar a gallon more for “additives,” well, they better have bathrooms with gold-plated bidets.

Lead photo: Gas station at night. (Photo: rnugraha/Flickr)