After Amazon named Queens one of the winners of its reality-television-style competition to build a second headquarters, real estate in Long Island City flipped upside down. Overnight, a sluggish buyer’s market became a seller’s paradise. Real estate firms reported sales of many times their usual volume. Stories of brokers selling units sight unseen via text tickled developers, even if other New Yorkers greeted the news with terror.

Now that Amazon is breaking off its engagement with the Big Apple, the passion that stoked the HQ2 buying frenzy has evaporated. So what happens next for Long Island City and neighborhoods nearby? Some residents think that Queens dodged a bullet: Jeff Bezos’ prosperity bomb would have terraformed the neighborhood, they say, driving out longtime residents in favor of soul-cycling engineers. Instead, Queens faces a different problem: the status quo, which might be more daunting than the worst-case scenario under Amazon.

Not everyone believes that Amazon’s non-arrival will mark a huge change in course for Queens. Long Island City “is not a neighborhood based on Amazon,” says Brendan Aguayo, a senior managing director at Halstead Property Development Marking, which sold two units in a Long Island City condo building to Amazon employees within a week of the first HQ2 announcement. “For all the reasons they decided on [Long Island City] to begin with, we are confident the neighborhood will thrive well beyond when this fades into the background.”

Neither he nor Lauren Bennett, a Corcoran broker who sold five units in Long Island City after the news of Amazon’s arrival, would say whether their HQ2-connected clients had expressed any buyer’s remorse. One unit in Bennett’s portfolio—a three-bedroom condo on 51st Avenue that had languished on the market for eight months without an offer—became the object of a bidding war after the mere rumor of Amazon’s move to Queens. The New York Post reported that the winning bid was $300,000 over the initial offer and above the $1.49 million asking price. (Bennett declined to answer questions about the status of this sale or others.)

But plenty of brokers feel far less optimistic than Aguayo. One told Bloomberg that Long Island City, which anticipated a transformation into a tech hub, was fated to remain a bedroom community for Manhattan commuters. Nancy Wu, an analyst for StreetEasy, said in an email that the turnabout highlights the risk involved with speculative investment in New York. “Now that the company has decided against setting up their new headquarters in Queens, we expect asking prices and buyer interest to fairly quickly revert back to their pre-announcement levels,” she said.

Before Amazon announced its plans to move into Queens and kicked off a gold rush, local sales were stagnant. Sellers were slashing prices. Inventory was overbuilt: up 62 percent in October of 2018 over the same month the year prior. Before the rumor of HQ2, it looked like it would take years for this housing market to return to a point of equilibrium.

Brokers who stood to make a mint in a buoyant market are frustrated by Amazon’s reversal, of course. But so are some of New York’s most vulnerable residents. Presidents of the tenant associations for four New York City Housing Authority public housing developments in Queens issued a statement condemning the leaders who they believe drove Amazon away from the bargaining table.

“New York has now lost 25,000 good-paying jobs,” reads the statement from the presidents of the Astoria, Queensbridge, Ravenswood, and Woodside Houses tenants associations. “The City and State will now lose tens of billions of dollars in revenue that could have been invested in NYCHA, and the tenants we fight for every day.”

Their letter highlights a central tension to the Amazon drama. Tenants of low-income housing broadly supported the move, in the hopes that it would bring higher-paying jobs and spillover effects to the neighborhood. More affluent residents, meanwhile, mounted a NIMBY campaign over the prospect of rising rents. Tyquana Rivers, a Democratic political consultant, told the New York Times that the gentrifiers’ complaints about Amazon mirrored the fight to keep Ikea out of Brooklyn. Indeed, residents in Jackson Heights are going to court to stop a Target from opening.

Dear anyone who thought this was compelling in yesterday's @nytimes:

— Armando Moritz-Chapelliquen (@ThatArmandoMC) February 14, 2019

“You have moved into a neighborhood that was already moving upwards in rent,” …“You’re complaining about something you’ve done. The hypocrisy is deafening.”

This is you: https://t.co/xaaK5aw9LG h/t @thenib pic.twitter.com/4PKQLvGcbg

Critics of the Amazon deal, including Queens Neighborhoods United, fear that the deal would have inevitably driven out current residents. The group also opposes a new train option linking LaGuardia Airport with the 7 Subway and Long Island Rail Road lines for the same reason: displacement. It is a powerful argument to marshal against transit, retail, jobs, and, above all, more dense housing.

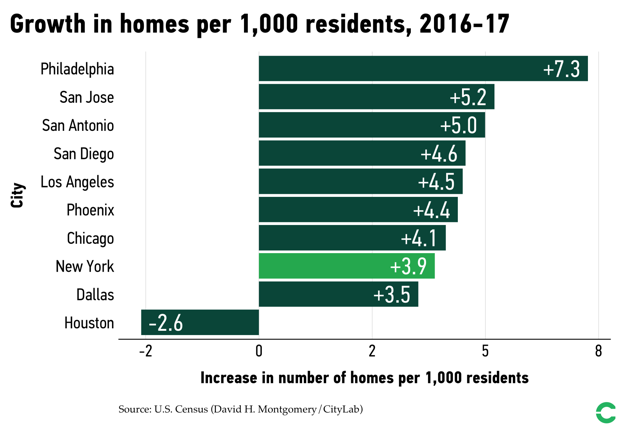

But the city is struggling to keep up with the demand for places to live. New housing construction lags well behind Philadelphia; the city’s on par with Chicago, according to the most recently available data from the Census Bureau. (Note that Houston suffered major devastation during Hurricane Harvey.)

Before Amazon, Queens was marked by a local oversupply of luxury condos and a shortage of affordable housing. In the first quarter of 2018, permits for new housing units were down 44.6 percent in Queens over the same time period a year before—far lower than any other borough. Average building size fell from 15.4 units in the first quarter of 2017 to 7.5 units in 2018. According to New York University’s Furman Center, the share of low-income households in Queens who were severely rent burdened in 2016—meaning they spent more than 50 percent of their income on rent—was 48.7 percent, the highest share of all five boroughs.

Building new affordable units in Queens can be a challenge. A brief flashback: A year before Amazon came calling, in November of 2017, a plastics manufacturing group and longtime landlord in Long Island City called Plaxall announced a plan to rezone its parcel along the Anable Basin—the same parcel where Amazon briefly planned to build its new headquarters. Plaxall planned to use the site to build a 700-foot-tall tower as an anchor of a development that would include 5,000 new housing units. Per the city’s Mandatory Inclusionary Housing program, 1,250 of the proposed condominium units would be subsidized low-income housing apartments.

But this plan too came under fire from critics who said it would lead to displacement. In January of 2018, the Municipal Art Society of New York, a non-profit preservation and planning group, issued a lengthy objection to the Anable Basin rezoning scheme. The organization questioned the scale of the proposed development and the lack of community outreach. Housing more residents would stress area parks, schools, and water and sewer infrastructure. While the organization claimed to recognize the importance of accommodating growth in the city, the group objected that the traffic, noise, and shadows would be too much for Long Island City to bear.

Later, when the housing plans for the Anable parcel were tabled in favor of Amazon’s HQ2 offer, the Municipal Art Society objected to these plans too. In the New York Times, Municipal Art Society president Elizabeth Goldstein voiced the “against” side in a pro- and anti-Amazon debate. In her argument, she cited many of the same reasons for opposing Amazon as the group had for opposing the prior zoning plan. Yet Goldstein also complained that Amazon would preclude the possibility of building affordable housing on the site—even though her organization was a prominent voice in the battle against building housing there.

“Even the affordable units planned as part of a recent rezoning of Anable Basin now appear to be in jeopardy, as the site will instead be used to create office space for as many as 25,000 Amazon workers,” she wrote.

It’s not clear whether the original rezoning plan is now back on the table. Plaxall told Bloomberg that it was “extremely disappointed” by Amazon’s departure. The company has not responded to a question about whether its former plans for building housing in Queens is back on now that the HQ2 deal is off.

But those affordable housing units were in jeopardy before Amazon arrived, and they will be in jeopardy after Amazon’s departure, if that plan is revived. Making housing affordable in Queens means building lots of new housing in Queens. That isn’t happening, despite the cranes and towers popping up in a few places.

Queens residents still face the prospect of exploding rents, soaring property taxes, and the creep of luxury condo dwellers and the services that cater to them. But now it won’t be Amazon’s doing. So long as Queens residents oppose construction of even affordable housing, the only growth possible will be in the luxury tier.

This story originally appeared on CityLab, an editorial partner site. Subscribe to CityLab’s newsletters and follow CityLab on Facebook and Twitter.