I give a lot of public talks on environmental issues, especially climate change. Every time, someone will suggest that to avoid catastrophe and suffering the best solution is to control population growth. Recently I’ve found myself giving a simple response—that the women of the world already have that under control, and if we can just maintain their rights and opportunities we can move on to the more challenging drivers of climate change and poverty: overconsumption, polluting technologies, and inequality.

Instead of the ever-increasing human population numbers some anticipated, overall population growth is now decelerating, and population numbers will level off or decline this century. Fertility rates—the average number of children a woman will have in her reproductive years—have plunged in the last 50 years in what the Economist has called one of the most dramatic social changes in history.

I often see a surprised reaction when, in the Southwest United States, with its fears of uncontrolled Latin American populations and immigration, I point out that fertility rates in Latin America have plummeted from six children per women to only 2.2 in 50 years. At a fertility rate of six, the population effectively triples with each generation; at 2.1 each person is replaced and the population does not grow at all.

While I was fortunate to have access to contraception, millions of women did not have that choice. Perhaps, I wondered, if birth control was more easily available, would population growth slow?

Those who see uncontrolled population growth as a threat to humanity’s future are often called Malthusians—after Thomas Malthus, whose “dismal theorem” of 1798 saw unchecked population growing much faster than food supply, with inevitable collapse and misery to follow. Malthus blamed the poor for a lack of moral restraint that then led to their own impoverishment and hunger. He was criticized, but his ideas persisted. As a student I first read and was convinced by ecologist Paul Ehrlich’s 1968 best-selling book The Population Bomb, which warned of mass starvation and pollution from overpopulation.

But then one of my teachers assigned a 1974 essay by geographer David Harvey (“Population, Resources and the Ideology of Science”), which opened my eyes to the links between population, inequality, and resource use. Harvey critically examines the argument that overpopulation occurs when resources are insufficient to meet our needs. He suggests that such overpopulation theories often lead to political and social repression of the poor and their aspirations by elites, and re-frames the problem as one in which social organization and inequality creates scarcities of things we need or wish to consume. Harvey suggests solutions that include altering consumption, re-thinking resource options, and reducing inequality.

Even more eye-opening as a young woman was the growing realization that the population growth rate depended to a very great extent on the options available to women. While I was fortunate to have access to contraception, millions of women did not have that choice. Perhaps, I wondered, if birth control was more easily available, would population growth slow? Then I read sociologist Mahmood Mamdani’s The Myth of Population Control: Family, Caste, and Class in an Indian Village, which showed family planning and birth control, on their own, do not lead to lower fertility because poor people often have many children—some die in childhood, and they need them to work the land and to look after them in old age.

People will have fewer children when they become an economic cost rather than a benefit, and when infant mortality declines. This is backed up by the work of Nobel Prize winner Amartya Sen, who shows how the empowerment of women in Kerala, India, resulted in much lower fertility rates and improved well-being.

Women will choose to have fewer children—to reduce fertility—when they have higher status; more options; living standards that include higher levels of education, literacy, employment, health care, and savings; a higher average age of marriage; and safe contraceptive choices. Because many of these indicators have actually improved for many (but not all) women worldwide, women and their partners are making choices to have fewer children to enhance the overall well-being of their families.

So, as women’s opportunities and rights have increased around the world, fertility rates have fallen steeply and are projected to fall even further. The latest United Nations projections include an optimistic scenario (the low variant) that sees the world reaching replacement fertility (2.1) in the next 10 years and reaching peak population of 8.3 billion people in 2050 and then declining. A medium variant sees replacement fertility in 2070 and a higher population of 10 billion.

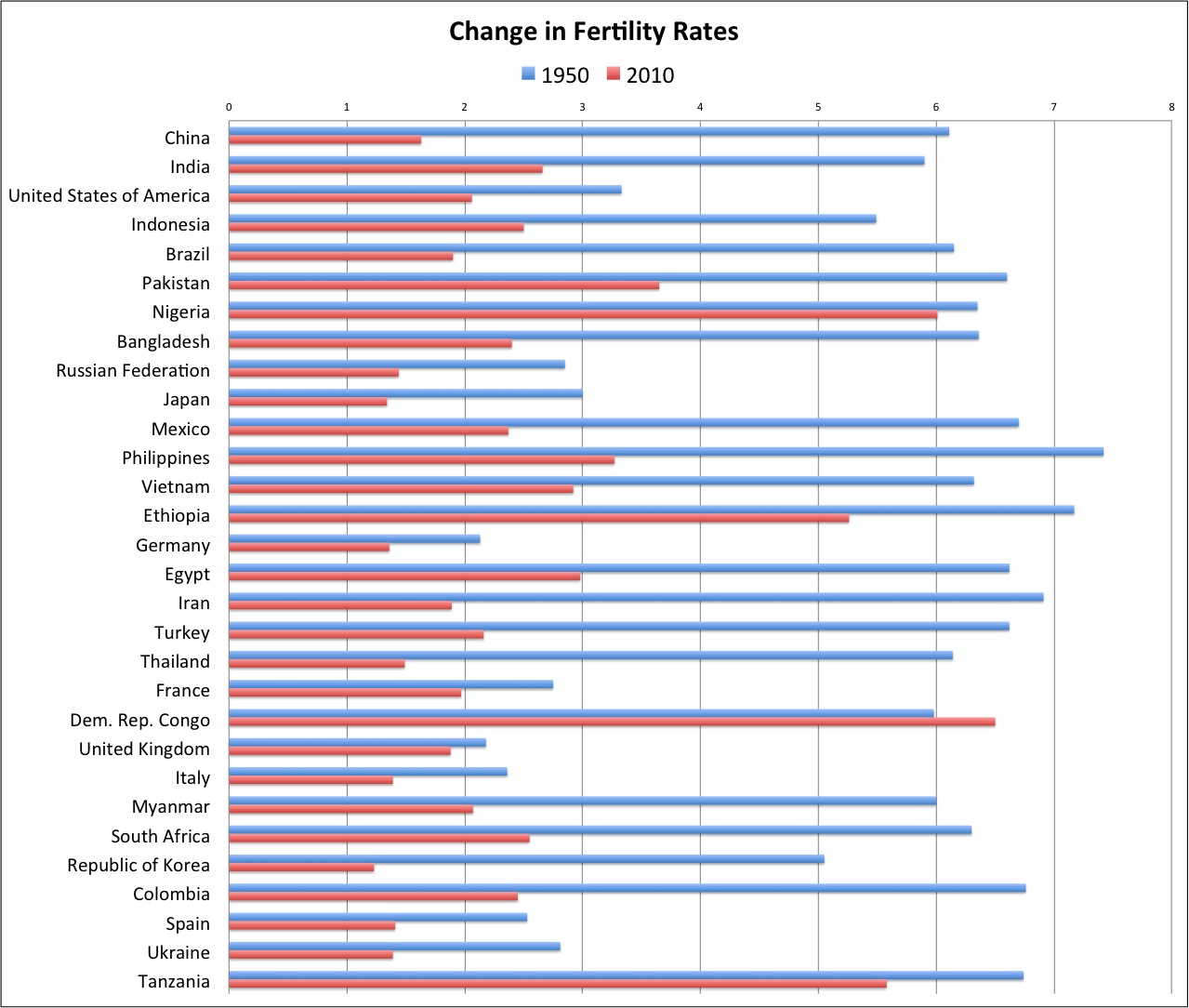

Some of the world’s most populous countries—24 of the 28 that are home to more than 75 percent of the world’s population—have seen dramatic drops in fertility since 1950. Several dropped from more than six to below replacement fertility, including China (6.1 to 1.6), Brazil (6.2 to 1.8), and Iran (6.91 to 1.89), joining the U.S., Japan, Russia, and most of Europe with low fertility. Some have halved their rates to less than three: Bangladesh (6.4 to 2.4), India (5.9 to 2.6), Indonesia (5.5 to 2.5), Mexico (6.7 to 2.3), Vietnam (6.32 to 2.92), and Egypt (6.62 to 2.98). The Philippines dropped from 7.42 to 3.27 and Pakistan from 6.6 to 3.8.

Several large African countries, however, still have high or slowly declining fertility rates, including Ethiopia (7.17 to 5.26), Nigeria (6.4 to six), Tanzania (6.74 to 5.58), and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where the fertility rate has actually increased (5.98 to 6.5). These countries tend to have high levels of poverty or large rural populations, but they also have considerable land area and resources that can, for the most part, support these populations. But there are other poor and rural countries in Africa where fertility rates have declined significantly—Rwanda (eight to five), Ghana (6.22 to 4.22), and Botswana (6.5 to 2.9)—as a result of reductions in conflict and improvements in women’s status, employment opportunities, higher incomes, and urbanization.

To be sure, the population is still growing; those of us who were born when fertility rates were higher are a large cohort, even if we’re having fewer children ourselves. This population momentum means we need to plan for more people even as growth slows and turns around. And as families become better off, their overall consumption will increase even if the family size is smaller.

This, then, is the sustainability challenge—not to control population growth, but to find ways to improve well-being and satisfy basic consumption desires without repression or environmental degradation, especially to minimize pollution, biodiversity loss, and greenhouse gas emissions. If we continue to reduce poverty and make sure that women have access to education, rewarding work, adequate incomes, health, contraception, and political rights, then the challenge of absolute population numbers on the planet will turn around about as quickly as possible.

So stop asking about overpopulation and population growth rates. Ask, instead, about overconsumption, affluence, waste reduction, and sustainable technologies—they are the more difficult drivers of environmental change to turn around at this point.