In the early 1990s as a graduate teaching assistant in botany I received my first lesson in United States history. Our lab supervisor conspiratorially shared with me that in his attic he kept a trophy his grandfather had left for him—the severed finger of a lynched black man.

I was an international student who had arrived from India a couple of years earlier, and this was my introduction to lynching. Puzzled over why I was the recipient of that confession or what I could do with it, I buried it within me. Now, years later, three University of California-Berkeley effigies take me back to that private lesson and the collection of human body parts, which I now know is a part of our collective history. Ferreted away in basements and attics are trophies and souvenirs of human parts, collections in small, private museums that stand as attestations to racial violence. Out of sight and therefore out of mind, these human fragments are mute testimony to the present moment.

Most of these skulls were picked up from the remains of already dead and decaying Japanese soldiers. They would sometimes turn up decades later in unexpected places during routine investigations.

In his book 100 Years of Lynching, Ralph Ginzburg reproduces an account of Sam Holt’s death, burned at the stake in Newman, Georgia. A story in the Kissimmee Valley Gazette, dated April 28, 1899, says not even the man’s bones were left in peace, “but were eagerly snatched by a crowd of people drawn from all directions, who almost fought over the burning body of the man, carving it with their knives and seeking souvenirs of the occurrence.” In a later lynching case the Chicago Record-Herald, dated May 23, 1902, reports that a mob of 4,000 persons in Lansing, Texas, burned Dudley Morgan to death. As the flames “died down relic hunters started their search for souvenirs. Parts of the skull and body were carried away.”

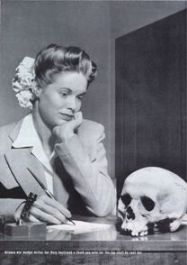

The rituals of collecting souvenirs continued in the Pacific theater during World War II. The gathering of Japanese combatants’ body parts by American soldiers was common enough practice that the U.S. Army issued a directive in January 1944 to prevent such acts. Yet the practice continued. Life magazine’s photograph of the week for May 22, 1944, depicts a 20-year-old white woman, pen in hand, enigmatically half-smiling at a skull that sits nearby. The caption reads:

When he said goodbye to Natalie Nickerson … a big, handsome, Navy lieutenant promised her a Jap. Last week, Natalie received a human skull autographed by the lieutenant and 13 of his friends and inscribed: This is a good Jap—a dead one picked up on the New Guinea beach. Natalie, surprised at the gift, named it Tojo. The armed forces disapprove strongly of this sort of thing.

As in the tragic case of “Tojo,” most of these skulls were picked up from the remains of already dead and decaying Japanese soldiers. They would sometimes turn up decades later in unexpected places during routine investigations—like Pueblo, Colorado, where, when searching a house for drugs in June 2003, detectives instead came upon a trunk that held a skull inscribed with neat letters and autographed by two to three dozen servicemen: “This is a good Jap. Guadalcanal, S.I. 11-Nov-42. Oscar. M.G. J. Papas, U.S.M.C.” The owner of the house wanted the skull back because it was a family heirloom inherited through his great-grandfather, Julius Papas; his unit had named the skull Oscar.

By the Vietnam War the U.S. military had strict rules in place on collecting human skulls and bones. Instead, accounts of necklaces made with human ears or fingers cut off from Vietnamese individuals abound. In October 2003, Toledo, Ohio’s Blade ran a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative report on war crimes in Vietnam by an elite U.S. fighting unit called the Tiger Force. The reporters note that prisoners were tortured and executed; their ears and scalps were collected as souvenirs. One soldier was recorded as having kicked out the teeth of executed civilians for gold fillings.

The four-and-a-half-year investigation—the longest lasting war-crime investigation of the Vietnam War—resulted in findings that 18 soldiers had committed war crimes ranging from murder and assault to dereliction of duty. But no one was charged. Though the U.S. Army opened an “active review” of the case, its public affairs office rarely returned the Blade’s requests for updates because by May 2004 they were, in their words, “too busy responding to prisoner abuse by U.S. soldiers in Iraq to check on the status of the Tiger Force case.”

Not even the bones were left in peace, “but were eagerly snatched by a crowd of people drawn from all directions, who almost fought over the burning body of the man.

By then we were dealing with Abu Ghraib in Iraq. Joe Darby, a reservist, had turned in a CD belonging to prison guard Charles Graner with images of abuses of Iraqi prisoners. Most of these images had been taken for private circulation, but the photographs at Abu Ghraib are not just one isolated example. Amid pictures of smiling soldiers, local farmers, and children, many images of detainee abuse including guns held at detainees’ heads and dead militiamen have turned up in Afghanistan on our troops’ laptops, and both digital and disposable cameras. Some photographs were meant for friends and family; others were meant solely for internal consumption. Mementos of deployment to Iraq and Afghanistan, CDs of images were copied and shared among platoon members.

To be sure, trophies collected from lynched victims and enemy combatants resonate differently among those who hold them—one as memorabilia perhaps of racial dominance, and the other of national triumph and the victorious rise of democracy. Regardless of origins and meanings, though, most Americans find such mementos revolting. The 1944 Life magazine photograph, for example, was met with outrage by its readership. And many descendants of war veterans are appalled by the human trophies they find in their homes. They turn their grandfathers’ memorabilia in and the Army returns these souvenirs to Japan for proper burial.

Yet questions remain: Why were these body parts, almost all from people of color, collected in the first place? After all, there are no German skulls from World War II locked in small trunks that we know of. Why do people keep them?

We need to revisit the statement released by the artists at Berkeley who hung the effigies of lynched victims in memory of Laura Nelson, George Meadows, Michael Donald, Charlie Hale, Garfield Burley, and Curtis Brown. “These images connect past events to present ones,” they note, “referencing endemic faultiness of hatred and persecution that are and should be deeply unsettling to the American consciousness.”

Fingers in attics, skulls on writing desks, and shared images of detainees in Afghanistan are not just possessions of deranged individuals. Instead, these are memorabilia we need to collectively reckon with, and dig out from our own basements, attics, and memories in order to confront the present.