(Photo: Brian van der Brug/Los Angeles Times/Getty Images)

Black and Latino students tend to perform more poorly than their white and Asian counterparts in math and science classes. It would be easy to assume this is partly based on the prejudices of professors, and new research suggests that’s a valid critique.

But the problem it identifies isn’t overt racism. Rather, the issue is whether an instructor believes intelligence and ability are fixed or malleable.

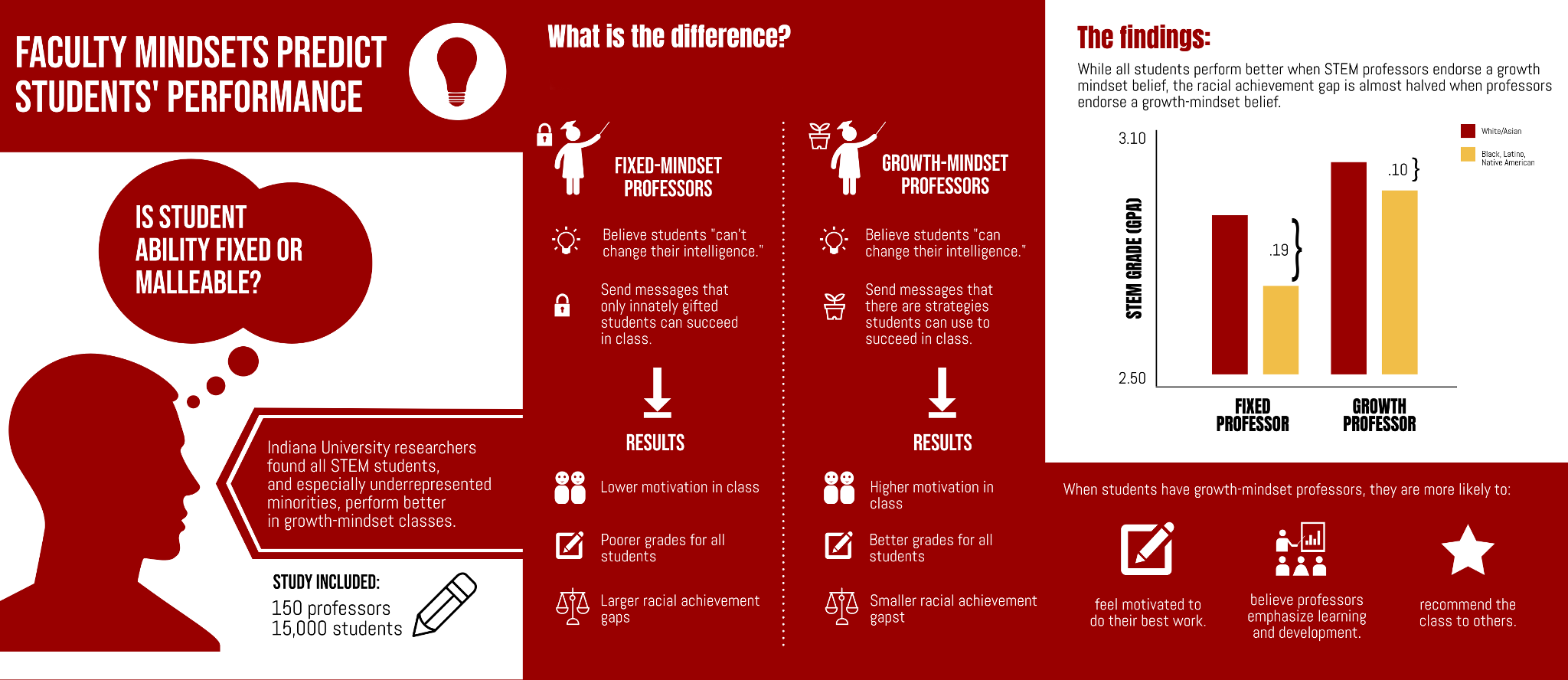

In a study featuring more than 15,000 students, the racial achievement gap in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) courses was found to be twice as large in courses taught by professors who expressed the latter attitude.

“Professors’ beliefs about the nature of intelligence are likely to shape the way they structure their courses, how they communicate with students, and how they encourage, or discourage, students’ persistence,” writes a research team led by Indiana University psychologist Elizabeth Canning. While this has important implications for all students, the researchers argue it can be particularly disadvantageous for minorities in that it can reinforce negative stereotypes about their race or ethnicity.

For the study, which was published in the journal Science Advances, the researchers surveyed 150 members of the STEM faculty at a “large, selective private university.” All 13 STEM departments were represented, including biology, computer science, mathematics, and physics.

The instructors expressed their level of agreement with two statements: “To be honest, students have a certain amount of intelligence, and they really can’t do much to change it,” and “Your intelligence is something you can’t change very much.”

Using university records, the researchers noted students’ grades in all 634 courses taught by the participating instructors over seven semesters. The 15,466 undergraduates were then divided into a “majority group” of whites and Asians, and an “underrepresented minority” group made up of African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans. The latter group represented about 11 percent of all students.

“On average, all students performed more poorly in STEM courses taught by faculty who endorsed more fixed mindset beliefs,” the researchers report. But minority students were negatively affected to a far greater degree.

Specifically, the grade point averages of white and Asian students were 0.19 points higher than those of minority students in courses taught by instructors who believed students’ intelligence was fixed and unchangeable. That achievement gap shrank to 0.10 points for courses taught by instructors who believe “ability is malleable, and can be developed through persistence, good strategies, and quality mentoring.”

The clearly harmful fixed-intelligence beliefs “were endorsed equally across the 13 STEM disciplines” the researchers sampled, and were just as likely to be endorsed by female as male faculty members.

Why did this mindset disproportionately affect underrepresented minorities? “Pervasive cultural stereotypes suggest that white and Asian students are more naturally gifted in STEM than black, Latino, or Native American students,” Canning and her colleagues write. “When teachers have lower expectations for their students, those students become less motivated, and perform more poorly in those teachers’ classes.”

The good news, they add, is that fixed-mindset beliefs are changeable.

“Studies have shown that cost-effective educational interventions can help people develop more of a growth mindset,” the researchers write. Shifting their attitudes on this key question “may be a potential lever to creating identity-safe college classrooms—learning environments where all students, regardless of race/ethnicity, feel they are valued and encouraged to reach their full potential.”

As this study reminds us, even very smart people like math and science professors can harbor prejudices. Getting them to acknowledge and release this particular belief system would help all students, and increase the likelihood that the research labs and STEM faculties of tomorrow look more like America.