James Gustave “Gus” Speth has lived his life at the extremes. He grew up in heavily segregated Orangeburg, South Carolina—then became an ardent supporter of civil rights. He was a consummate insider, chairing President Jimmy Carter’s Council on Environmental Quality and heading the United Nations Development Programme during the Clinton administration. Then he was arrested while protesting the Keystone XL pipeline outside the White House and spent three days in a D.C. jail.

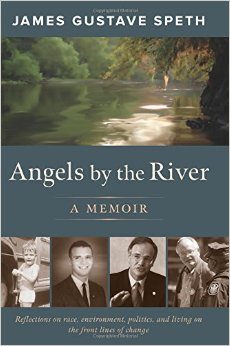

In addition to serving the government and rabble rousing, Speth found time to help launch two leading environmental organizations: NRDC (which publishes Earthwire) and the World Resources Institute. He was dean of the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies for a decade, and recently, he published his memoir, Angels by the River. Here, the author discusses everything from his Jim Crow childhood to the future of democracy—and, of course, the current state of the Earth.

You’re a southerner who became a civil rights supporter, then an environmental activist. How did the first lead to the second?

I grew up in Orangeburg, South Carolina, a Jim Crow town. It was lovely in many ways but deeply committed to the perpetuation of racial separation and segregation. People didn’t question that—and to my continuing embarrassment, neither did I, until I went off to Yale and had some sense knocked into my head.

“Now I hope that environmentalists all over the country, young and old, are joining the Ferguson protests and participating with the frontline groups—those most impacted by what I would call a system of injustice.”

When you realize that your childhood values represented a system of vast injustice, the scaffolding collapses around you. Once I was freed, I could make my own decisions about what was important. I had also been too close to the wrong side of history, and I never wanted to get that close again. If I had the chance to throw myself 100 percent into a great movement of national and international importance, I wanted to seize that opportunity. That opportunity was the environment.

What can the environmental movement learn from the civil rights movement?

We grew up, intellectually, with the Civil Rights Movement. We saw the power of protests and the effectiveness of major litigation. We saw what could happen when Congress acted, as it did in 1964 and ’65 with major civil rights legislation. Although environmentalists were inspired by these successes, we didn’t form tight bonds with the Civil Rights Movement or minority communities. We found our own silo. I think that was a great tragedy.

Now I hope that environmentalists all over the country, young and old, are joining the Ferguson protests and participating with the frontline groups—those most impacted by what I would call a system of injustice. It’s unjust to black communities, it’s unjust to marginalized people of all sorts, and it’s certainly unjust to future generations. Environmentalists need to be with those who are running forcefully at these injustices that cut across big swaths of our country.

At the end of his tenure, you told President Carter that no administration had done more for the environment. More than 30 years later, is that still the case?

In terms of presidential leadership, we haven’t had a match for Jimmy Carter. President Obama seems to have finally gotten the message on climate change and seems to be doing what he can under the political circumstances, but it’s not the kind of leadership the issue now requires.

He should be leading a much more sustained process of education, bringing scientists and science to the public and connecting it to powerful narratives to give people a fuller understanding. He has to relate climate change to what’s happening in everyday lives. The president should have the capacity to do that.

You were in the administration when the government first seriously considered the threat of anthropogenic climate change. Have you been surprised at how the controversy has played out?

It’s beyond surprising—it’s been a shock and a tragedy. When we first wrote the reports in the late 1970s and early ’80s, we assumed people were sensible enough that if we could actually detect, unquestionably, the signals of climate change, then action would follow. In our naive view, that would have been enough to wake everyone up. Who in the world wants to ruin the planet’s climate?

(Photo: Chelsea Green Publishing)

Two fundamentally unethical things happened. First, there is a group of ideologically driven individuals and organizations with an anti-government, anti-regulation belief system. The strong government intervention needed to respond to climate change would undermine their ideology.

Second, we have powerful people with economic interests who know exactly what’s going on. Unlike the ideologues who cloud their heads with a lot of nonsense, the executives of the big energy companies know they are destroying the climate for future generations. Yet, they persist in trying to make as much money and to sell as much fossil fuel as they can. It’s a deeply unethical, immoral position. This is why the disinvestment campaign is so important. We need to shame these individuals for what they’re doing. They’re getting away with murder and planetary destruction right now.

The environmental movement seems to be shifting. Groups like Bill McKibben’s 350.org argue that massive protests and youth engagement, not lawyers and lobbyists, are the future. Are these approaches complementary, or is there a danger of a splintering among advocates?

We’ve always had splinters within the environmental community, but I think those approaches are complementary. Here is my complaint: We have to ask again, What’s an environmental issue? The traditional answer is air and water pollution, biodiversity, and climate change.

“The executives of the big energy companies know they are destroying the climate for future generations. Yet, they persist in trying to make as much money and to sell as much fossil fuel as they can. It’s a deeply unethical, immoral position.”

What if the real answer is, “It’s an issue that determines environmental outcomes—an issue that affects our ability to be successful in protecting the environment?”

Once you define it that way, you realize there are deeper things underlying our current causes and deeper problems that should be thought of as environmental issues: the failing of our democracy, the depth of social and economic insecurity, and our consumerism. These are profound environmental issues that affect whether we win or lose. Our community, writ large, has to deal with those issues in a powerful, effective way, with all the strength it’s got. That’s my challenge to all of us, really, and to NRDC, which I love dearly.

What are you planning for your next act?

I was lucky and very fortunate to have the funds and resources to help launch NRDC and the World Resources Institute. Now I’m trying to find some resources to help build the institutional infrastructure of the new economy. I’ve spent a lot of time on the development of the New Economy Coalition. I have another project with the Democracy Collaborative, called the Next System Project. We are trying to open a national conversation about moving beyond this rapacious, ruthless form of capitalism we have today. We can be committed, honestly committed, to people, to place, and to planet.

This post originally appeared on OnEarth as “Greenery and Justice for All” and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.