In American English books from 1910 to 1950, about 25 percent of the uses of “family” were preceded by “the.” Starting about 1950, however, “the family” started falling out of fashion, finally dropping below 16 percent of “family” uses in the mid-2000s. This trend coincides with the modern rise of family diversity.

In her classic 1993 essay, “Good Riddance to ‘The Family,’” Judith Stacey wrote that “no positivist definition of the family, however revisionist, is viable … the family is not an institution, but an ideological, symbolic construct that has a history and a politics.”

The essay was in the Journal of Marriage and the Family, published by the National Council on Family Relations. In 2001, in a change that, as far as I can tell, was never announced, JMF changed its name to Journal of Marriage and the Family, which some leaders of NCFR believed would make it more inclusive. It was the realization of Stacey’s argument.

I decided on the title very early in the writing of my book: The Family: Diversity, Inequality, and Social Change. I agreed with Stacey that the family is not an institution. Instead, I think it’s an institutional arena: the social space where family interactions take place. I wanted to replace the narrowing, tradition-bound term, with an expansive, open-ended concept that was big enough to capture both the legal definition and the diversity of personal definitions. I think we can study and teach the family without worrying that we’re imposing a singular definition of what that means.

It takes the unique genius that great designers have to capture a concept like this in a simple, eye-catching image. Here is how the artists at Kiss Me I’m Polish did it:

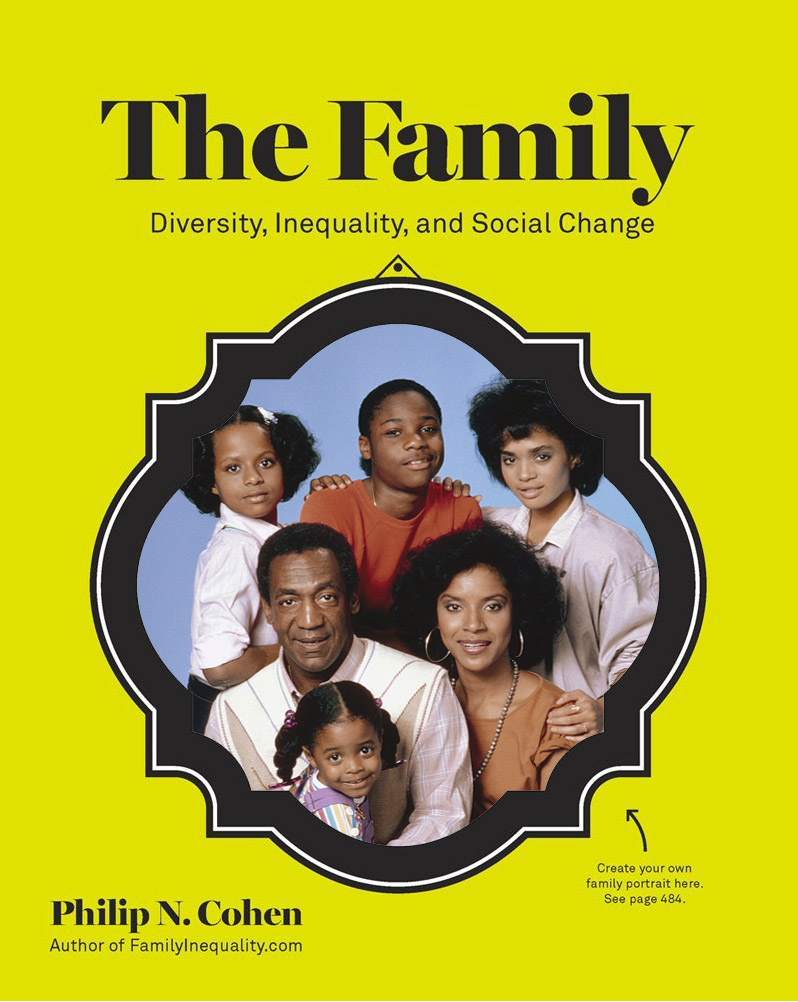

What goes in the frame? What looks like a harmless ice-breaker project—draw your family!—is also a conceptual challenge. Is it a smiling, generic nuclear family? A family oligarchy? Or a fictional TV family providing cover for an abusive, larger-than-life father figure who lectures us about morality while concealing his own serial rape behind a bland picture frame?

WHOSE FUNCTION?

Like any family sociologist, I have great respect for Andrew Cherlin. I have taught from his textbook, as well as The Marriage Go-Round, and I have learned a lot from his research, which I cite often. But there is one thing in Public and Private Families that always rubbed me the wrong way when I was teaching: the idea that families are defined by positive “functions.”

Here’s the text box he uses in Chapter 1 (of an older edition, but I don’t think it has changed), to explain his concept:

I have grown more sympathetic to the need for simplifying tools in a textbook, but I still find this too one-sided. Cherlin’s public family has the “main functions” of child-rearing and care work; the private family has “main functions” of providing love, intimacy, and emotional support. Where is the abuse and exploitation function?

That’s why one of the goals that motivated me to finish the book was to see the following passage in print before lots of students. It’s now in chapter 12, “Family Violence and Abuse”:

We should not think that there is a correct way that families are “supposed” to work. Yes, families are part of the system of care that enhances the lived experience and survival of most people. But we should not leap from that observation to the idea that when family members abuse each other, it means that their families are not working. … To this way of thinking, the “normal” functions of the family are positive, and harmful acts or outcomes are deviations from that normal mode.

The family is an institutional arena, and the relationships between people within that arena include all kinds of interactions, good and bad. … And while one family member may view the family as not working—a child suffering abuse at the hands of a trusted caretaker, for example—from the point of view of the abuser, the family may in fact be working quite well, regarding the family as a safe place to carry out abuse without getting caught or punished. Similarly, some kinds of abuse—such as the harsh physical punishment of children or the sexual abuse of wives—may be expected outcomes of a family system in which adults have much more power than children and men (usually) have more power than women. In such cases, what looks like abuse to the victims (or the law) may seem to the abuser like a person just doing his or her job of running the family.

HUXTABLE FAMILY SECRETS

Which brings us to Bill Cosby. After I realized how easy it was to drop photos into my digital copy of the book cover, I made a series of them to share on social media—and planning to use them in an introductory lecture—to promote this framing device for the book. On September 20 of this year I made this figure and posted it in a tweet commemorating the 30th anniversary of The Cosby Show:

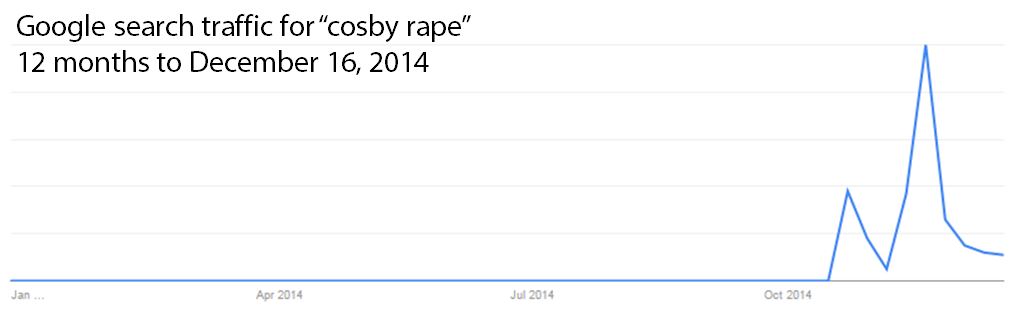

Ah, September. When I was just another naïve member of the clueless American community, using a popular TV family to promote my book, blissfully unaware of the fast-approaching marketing train wreck beautifully illustrated by this graph of Internet search traffic for the term “Cosby rape”:

I was never into The Cosby Show, which ran from my senior year in high school through college graduation (not my prime sitcom years). I love lots of families, but I don’t love “the family” any more than I love “society.” Like all families, the Huxtables would have had secrets if they were real. But now we know that even in their fictional existence they did have a real secret. Like some real families, the Huxtables were a device for the family head’s abuse of power and sexuality.

So I don’t regret putting them in the picture frame. Not everything in there is good. And when it’s bad, it’s still the family.

This post originally appeared on Sociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner site, as “Why I Called It The Family’ and What That Has to Do With Cosby.”