Today’s Pakistani Taliban attack on a Peshawar school has resulted in the deaths of at least 145, many of them children. In Sydney, meanwhile, Monday’s fraught café hold-up left two innocent people dead. Then there’s Yemen. And Darfur. And Nigeria. It’s a seemingly endless news cycle of violence, and it can be hard to find even a sliver of hope.

Thanks to Twitter hashtags like #prayforpeshawar and #illridewithyou—a sign of anti-Islamaphobia—social media can help bring a sense of camaraderie and togetherness to people from around the world. But, it seems, when speaking about empathy, the personal touch is still best.

A recent study in the European Physical Journal Data Science assessed emotional reactions on Twitter over another tragedy—the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing—and found a link between firsthand experience and compassion on social media.

Lin observed a direct correlation with geographic proximity, social network connection, and personal experiences in Boston. That is, the closer someone lived to Boston, knew people in Boston, or had ever visited Boston, the greater the likelihood for an emotional reaction on Twitter.

University of Pittsburgh information sciences professor Yun-Ru Lin and her team raked through 180 million geocoded tweets, over a one-month span, from users in 95 cities—to be exact, the 60 most-populated United States cities and the 35 highest-populated cities outside of the U.S. Using a concept-based lexicon, the researchers tracked fear, solidarity, and sympathy. Solidarity and sympathy specifically were inferred from two prominent hashtags: #bostonstrong and #prayforboston, respectively. The report also dissected Twitter users’ exact relationship to Boston, by analyzing geographic proximity, personal connection, and direct, physical experiences with the city.

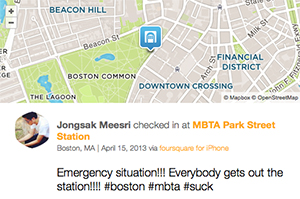

As one might expect, all three emotional responses garnered plenty of Twitter activity. “Emergency situation!!! Everybody gets out the station!!!! #boston #mbta #suck,” one person wrote, falling into the “fear” group. “Such an emotional week for this country. Never been more proud to be an American. #BOSTONSTRONG, #WestTX” tweeted another, demonstrating the solidarity Lin predicted in some users.

In all three categories, Lin observed a direct correlation with geographic proximity, social network connection, and personal experiences in Boston. That is, the closer someone lived to Boston, knew people in Boston, or had ever visited Boston, the greater the likelihood for an emotional reaction on Twitter. This is an important result, as it belies the hypothesis that increased globalization will inherently lead to greater global empathy.

“We find that the personal visit is the dominant relationship. This event relates to the community with the most personal experience with the area,” Lin says. “Not just because you connect with the people there by social media, but also because you had traveled to the area. This particular study, we also collected all the historic tweets a person had. That’s how we know about a visit, by a tweet: ‘I’m here, in this city.’”

Lin also notes that fear is not actually a bad thing in this case. “Those people that display solidarity is the same community—those people that are most fearful,” Lin says. “Fear also has a productive role in a social component.”

Interesting outliers did of course exist, like London, where most citizens were more restrained in expression of fear and solidarity, but used the #prayforboston—an indicator for sympathy—liberally. Lin theorized that this stems from London’s own then-recent terrorist attacks, stirring up a greater sense of empathy.

Lin’s study provides an interesting lens to view today’s headlines, in particular the #prayforpeshawar and #illridewithyou hashtags. In spite of an increasingly connected world, in the face of adversity, a personal touch is still most effective.

“I think our findings would apply to events like [Sydney and [Pakistan]. If you want to find the communities that care or are concerned the most, of course you should look at that based on travel and social relationship to the area,” Lin says. “These people will feel concerned the most.”