In most contexts, we take two-party voting for granted. As voters head to the polls on Tuesday, many are planning how best to choose between two candidates—in some cases, the lesser of two evils. But some will have a few extra choices on their ballots—even a few dozen.

In Oakland, California, Democrats won’t face up against Republicans at the polls. In fact, voters won’t chose between two candidates at all—they’ll have 15 choices (plus a write-in, if they’re still unsatisfied).

Ranked choice or instant runoff voting was first created by an American architect in the late 1800s. Though it’s been adopted in countries around the world, ranked choice only somewhat recently landed back stateside. A handful of cities across the country have adopted ranked choice for local elections in recent years, but the San Francisco Bay Area has emerged as a true testing ground for this civic innovation—non-partisan voting reform seems like a natural fit for a region dominated by Democrats. San Francisco held its first ranked-choice election in 2004. Across the Bay, Oakland, Berkeley, and San Leandro held their first ranked-choice elections in 2010.

The Oakland ballot describes ranked choice as “voting made easy,” but the system is far from universally popular. When California Governor Jerry Brown voted in Oakland’s election last week, he told reporters that he found “this ranked-choice system very complexifying.”

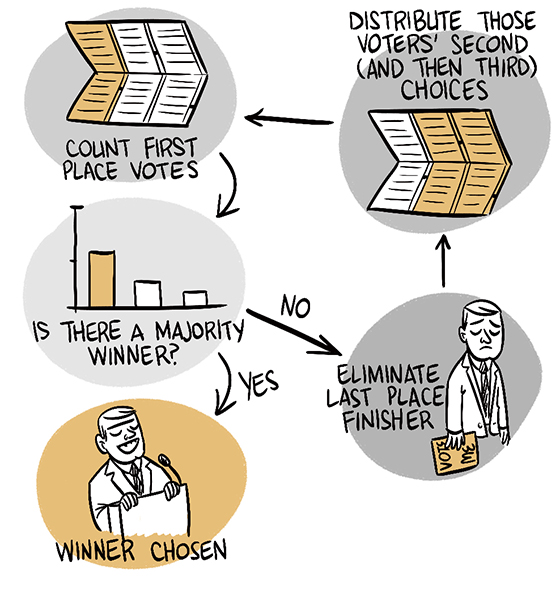

It’s not that the act of voting in a ranked-choice election is particularly or exceptionally difficult: Instead of one column for one vote, the ballot features three columns, for a first, second, and third choice vote. If no candidate emerges with a majority after the first place votes are tallied, the second and third choices come into play.

This allows for the election of candidates who might not get a majority of votes—a dynamic that makes some voters feel the system is anything but “fair.” When Oakland mayor Jean Quan won in 2010 after multiple rounds of vote counts, many claimed her win was illegitimate and that she did not have the peoples’ mandate.

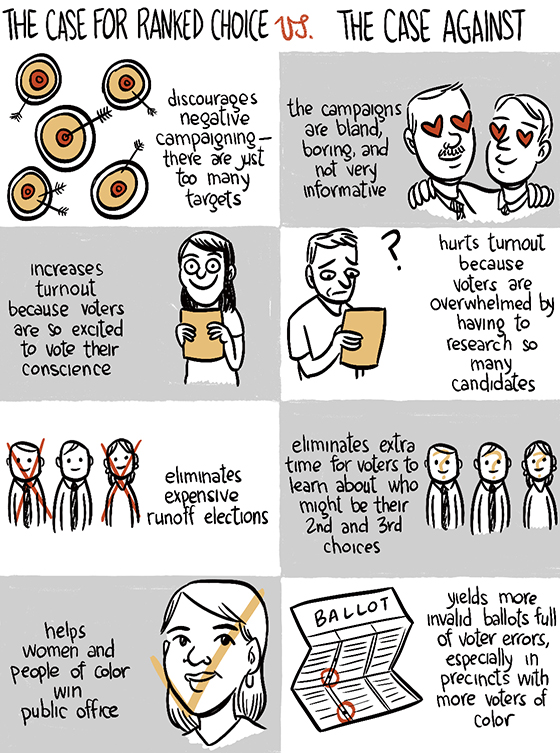

Ranked choice’s biggest proponent is the non-profit Fair Vote, which aims to create a more representative democracy “in which most Americans can elect representatives and hold them accountable, in which city voters are as important as suburban voters, in which people of color and women are as likely to win representation as white men and in which campaigns provide opportunities for substantive debate about a full range of policy ideas.” Ranked-choice boosters say the system yields a host of social and political benefits, but the system’s detractors are just as passionate. Many claims on both sides are disputed or under-researched.

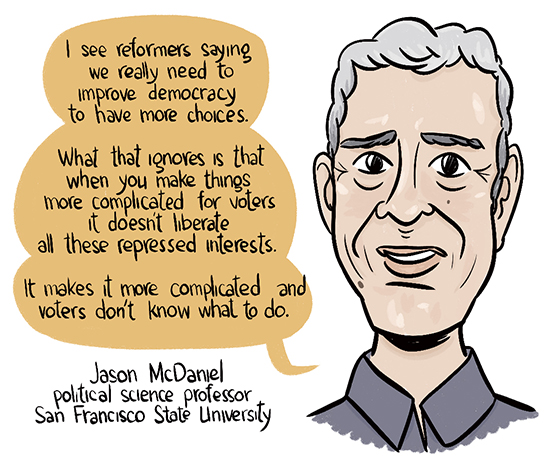

Ranked choice is not intended purely to shift voting methods, but to shift politics. This is what makes voting researcher and political science professor Jason McDaniel skeptical.

McDaniels’ research, published in September, indicates that ranked-choice voting does not encourage more turnout at the polls, and it likely leads to more scrapped ballots when voters make mistakes.

As Brown said, it’s “complexifying.”

Ranked-choice voting is also not immune to strategic plays. It may lead to nicer campaigns, but it can also lead to strange ones: In recent weeks, three Oakland mayoral candidates announced their own alliance, in the style of competitive reality television. This may not be consistent with the stated goals of ranked choice, but any voting system is subject to potential manipulation.

“I suspect that ranked choice just doesn’t like elections, it doesn’t like candidates—it wants to make them behave differently and make voters behave differently,” McDaniel says.

Ranked choice has lofty goals for an algorithm. But no voting system is likely to undo the deep structural inequalities that have led to 65 percent of American political positions being held by white men, who make up only 31 percent of the population. A parliamentary, multi-party political system might trickle up from crowded municipal elections, but new ballot systems seem like a slow way to effect change.

Turnout at the polls this week in Oakland is expected to be very low—but that might not be ranked choice’s fault at all. The most direct way to encourage more fair representation at the ballot box might just be timing local elections to coincide with more popular national ones.

But, ultimately, perhaps any voting system is just the lesser of two evils.