In November’s gubernatorial election in New York State, Green Party candidates Howie Hawkins and Brian Jones are running against Democratic incumbent Andrew Cuomo, who won his party’s primary. Hawkins and Jones are seeking to become the next governor and lieutenant governor respectively.

They’re hardly your typical politicians. Hawkins works at UPS in Albany, unloading trucks, and is a member of the Teamster’s union, while Jones is a teacher who taught for nine years in the New York City public school system.

“The idea is that without a genuine reckoning with what happened in the war on drugs, you can’t move forward and have justice. There has to be a public process to account for what was done.”

Hawkins and Jones understand that winning is a long shot, to say the least. A recent NBC 4 New York poll showed Hawkins getting just seven percent of the vote. Still, taking a longer view, siphoning away a proportion of the main parties’ voters can be a way to get them to shift their policies in your direction. And the Greens have long argued that building an alternative to the two-party system is crucial because Republicans and Democrats represent the interests of their wealthy corporate donors. The top industries that donate to Governor Cuomo’s campaign are finance, insurance, and real estate, while the Green Party portrays itself as a party for working people, and doesn’t accept contributions from corporations. “The richest one percent own the two major parties,” Hawkins says.

One area in which the Green Party platform differs radically from that of the Democrats is the war on drugs. So Substance.com spoke with both candidates to get their take on issues like mass incarceration, the racial disparities of drug-law enforcement, the legalization of heroin and other drugs—and what could happen after that.

How has the war on drugs impacted communities—particularly communities of color—in New York State under Governor Andrew Cuomo and former mayor Michael Bloomberg?

HAWKINS: Cuomo is a drug warrior and mass incarcerator. He has been silently complicit in the drug war, first as attorney general and then as governor—as Bloomberg and [former NYPD Commissioner] Kelly stop-and-frisk and now Mayor de Blasio and [NYPD Commissioner] Bill “broken windows” Bratton target poor communities of color for petty offenses, particularly marijuana possession.

The war on drugs hasn’t reduced substance abuse, but has created a culture of violence fueled by profits from the drug trade, similar to the crime wave that accompanied the prohibition of alcohol in the 1920s.

Despite decriminalizing the possession of small amounts of marijuana four decades ago, New York State leads the country in marijuana arrests. The greatest racial disparities occur in Brooklyn and Manhattan, where black New Yorkers are over nine times more likely than whites to be arrested for possessing marijuana.

JONES: It has been devastating. According to the New York Civil Liberties Union, the black arrest rate for marijuana has increased 26 percent since 2001. So under the watch of Cuomo and Bloomberg, the war on drugs has intensified. We are now at a point where some 50,000 people in New York State are snatched off the streets every year for this reason alone. And as we know, once these folks are saddled with a criminal record, they effectively become second-class citizens because it’s legal to discriminate against them.

TheNew York Times came out recently in favor of the legalization of marijuana. What’s your reaction to the new position of the “paper of record”?

HAWKINS: What took the Times so long? It is time for New York to also legalize, regulate, and tax recreational marijuana as Colorado and Washington State now do.

JONES: Better late than never. The New York Times can tell which way the wind is blowing, but has not gotten out in front on these issues.

You favor legalizing and regulating both marijuana and heroin. Do you have any concern that legal regulation could lead to an increase in the use of these drugs?

HAWKINS: Cuomo says marijuana is a gateway drug to hard drugs, but he is pandering to a public opinion cultivated by decades of drug war propaganda. Where marijuana and heroin have been decriminalized or legalized in countries like the Czech Republic, Netherlands, Portugal, Switzerland, and Uruguay, both marijuana and hard drug use have declined.

Look, marijuana is the third most popular recreational drug in America and has been used by nearly 80 million Americans. It’s much less dangerous than alcohol or tobacco. An editorial published in the medical journal the Lancet said in 1995 that pot smoking, even long term, isn’t harmful to health. Cuomo’s jihad against marijuana perpetuates New York State’s dubious status as the marijuana arrest capital of the world.

I also want to say something about medical marijuana. Because of Governor Cuomo’s interference with the Compassionate Care Act, the final medical marijuana bill that passed is the weakest in the country. Playing amateur doctor, the governor put himself between doctors and their patients and limited eligible diseases, modes of intake and supply to the point where it might not meet the demand for the medicine. Cuomo’s obstruction on the medical marijuana bill goes against the vast consensus of medical and scientific opinion. He is perpetuating the pain and suffering of seriously ill patients.

We can also save lives from the epidemic of opioid overdose deaths by allowing users to get treatment instead of potentially deadly fixes. If we treat drug abuse as a health problem rather than a law enforcement problem and provide drug treatment on demand instead of incarceration, we can save lives and undermine the unregulated, underground drug economy.

JONES: There are plenty of legal drugs that people can purchase right now. Whether or not substance abuse increases, it must be treated as a health issue. Why people abuse drugs has nothing to do with legalization. Legalizing marijuana and heroin, for starters, is about taking the violence out of drug use and drug dealing and creating the possibility of providing genuine treatment for people who need it. Arresting people, charging them, imprisoning them for using or distributing drugs only makes it harder for those people to make ends meet.

According to your platform, you are in favor of “Freedom and amnesty for all drug war prisoners currently serving time in prison or on parole for nonviolent drug offenses.” Do you believe New Yorkers share these positions? And how would you implement them?

HAWKINS: I haven’t seen a poll of New Yorkers on freeing non-violent drug offenders, but I’ve seen recent polls saying 79 percent of Texans and 73 percent of Floridians support it. I think it is safe to say a majority of New Yorkers does also.

There are steps we can take to better prepare people in prison and on parole for re-entry into society. Every person in prison and on parole should have the opportunity to further his or her education, whether it’s a GED program or a higher education program. Earlier this year Governor Cuomo abandoned a plan to provide public money for college courses at 10 prisons. Education reduces recidivism. As an example, Ohio reduced recidivism rates by more than 60 percent among ex-inmates who completed a degree in prison.

We know that more than 50 percent of incarcerated people have children. When parents participate in post-secondary education, the likelihood their children will go to college increases, creating more opportunities to climb out of poverty.

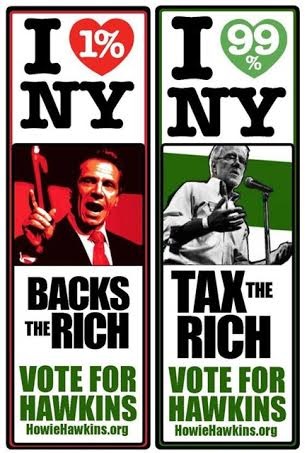

Howie Hawkins campaign material.

I want to restore eligibility for Federal Pell Grants and New York State Tuition Assistance Program Grants for people who have been in prison. And I include people in prison in my proposal for tuition-free education at CUNY and SUNY.

I also want to “ban the box” and prohibit employers from asking a potential hire to check a box on the initial job application, indicating if he or she has a criminal history, and defer such inquiry until a conditional offer of employment is made. I’m also in favor of restoring voting rights for people in prison and on parole.

JONES: There has to be more than just freedom and amnesty—there has to be reparations. As Michelle Alexander has pointed out, legalization will likely mean that a whole lot of white men start getting rich doing the very same thing that black and brown people have been doing for decades at the cost of their freedom and, in some cases, their lives.

I also think the issue of violent vs. non-violent offenders is tricky. I think freedom and amnesty for non-violent offenders makes intuitive sense to a lot of people, but when you start talking to former prisoners you realize that the boundary between “violent” and “non-violent” is up for debate.

Tell me about why you want a truth, justice, and reconciliation commission to address the impact of the war on drugs and mass incarceration.

HAWKINS: I’ve joined with Alice Green, the director of the Center for Law and Justice in Albany, to deliver 10,000 petition signatures from people around the state calling on the governor to establish a Truth, Justice, and Reconciliation Commission to study the impacts of mass incarceration on New Yorkers, largely brought about by the failed war on drugs. The commission will be a top priority of mine, along with a statewide public defenders’ program to provide due process for those accused of a crime.

I would name people to the commission who have been dedicated to equal justice under law and civil rights, like Alice Green and Ramon Jimenez, the Green candidate for attorney general—a Harvard-educated lawyer who has litigated criminal, labor, and tenants cases for people in his South Bronx neighborhood for 40 years.

The commission would be modeled after a South African commission established following apartheid. It would investigate the ways the state’s drug policies and justice system have led to high incarceration rates. In particular, it would assess the devastating impact on black and Latino communities. It would hear from the people most directly affected and recommend alternatives to mass incarceration. And it would look at reparations for the communities impacted.

JONES: The idea is that without a genuine reckoning with what happened in the war on drugs, you can’t move forward and have justice. There has to be a public process to account for what was done, who benefited, who suffered, why, and how. I think such a commission, to be truthful and truly representative, would have to include people living with the collateral consequences of criminal records, formerly incarcerated people, as well as advocates who work for justice in the system.

This post originally appeared on Substance, a Pacific Standard partner site, as “Should the Victims of the War on Drugs Receive Reparations?”