The Double Irish is not a traditional morning meal, as its name might lead one to believe. Nor is it a very niche form of video entertainment. It’s actually a corporate tax loophole that United States companies—including Apple, Google, and Yahoo—have been using to dodge paying millions in taxes in their home country. Now, however, Ireland has decided to sew the hole shut by 2020, with the backing of finance minister Michael Noonan. But could the threat of higher taxes drive out the businesses that the country has worked so hard to cultivate and cause thousands of jobs to vanish?

Ireland has draws other than loopholes: It’s the only English-speaking country in the Eurozone, it has a highly educated employment base, and it has the built-in momentum of already attracting a cluster of high-profile foreign companies.

The situation is one of conflicting incentives. U.S. companies seek out tax bargains in exchange for relocating international headquarters to Dublin, and Ireland profits from their tax dollars and the presence of high-tech firms—around 60 percent of Irish employees of international companies work in the technology industry, according to the New York Times. But the Double Irish has increasingly been the target of criticism from the Paris-based Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development as well as President Obama, who called the tactic “gaming the system.”

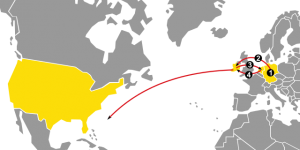

It does indeed have the feel of a game. The Double Irish requires two companies to be founded in Ireland, besides the original U.S. entity. One of the new companies is a tax resident of Ireland and the other is theoretically located in a tax haven like the Cayman Islands or Bermuda, which have artificially low tax rates to incentivize moving capital there. The tax-haven business owns the non-U.S. rights to the company’s intellectual property, which is licensed to the Irish branch. Thus, the Irish branch pays the majority of its profits in fees to the tax-haven branch, where taxes are lowest. The remaining profit of the Irish branch is taxed at the country’s corporate rate of 12.5 percent, low compared to the U.S. equivalent of 35 percent, which is one of the highest in the world.

Double Irish With a Dutch Sandwich. (Photo: Maxxl2/Wikimedia Commons)

The Double Irish can also be combined with another delicious-sounding tax dodge, the Dutch Sandwich, in which products from the Irish branch are shipped through a shell company in the Netherlands, which also has low tax rates, a move made simpler by Irish deals with some European Union members. Then, the Netherlands profits are routed through the tax-haven branch, thus avoiding Irish taxes entirely.

The Irish Industrial Development Authority (IDA) defended criticisms of the tax policy, noting that their mandate “is to create employment, investment and real tangible economic benefits for Ireland via foreign direct investment,” the Daily Mail reports. The IDA argues that there are real advantages to drawing companies this way: “Transactions that rely solely on tax benefits, without substance behind them, don’t bring economic benefits to Ireland.”

When facing the likely closing of the loophole, the question for policymakers becomes, what constitutes a tangible, stable investment by tech giants and what is just a short-term loss-leader for favorable tax policies? If companies are truly invested in maintaining their Dublin presence, then Ireland’s already favorable tax terms might keep them there. But if extremely low taxes are the only hook, then suddenly the offices and lucrative jobs vanish.

Early signs point to the former rather than the latter. Ireland has draws other than loopholes: It’s the only English-speaking country in the Eurozone, it has a highly educated employment base, and it has the built-in momentum of already attracting a cluster of high-profile foreign companies.

Google is said to be considering reinforcing its investment in Ireland, even after the news of the Double Irish closure, a move propelled by the company’s chief financial officer, Patrick Richette. Google currently employs over 2,500 staffers at its headquarters in the Dublin docklands, and it may soon bid on a $95 million complex next to its current offices to consolidate its base in the city and bring its employee numbers up past 3,000, according to the Irish Times.

The places that really suffer from the closure of the loophole might be the tax havens that host shell companies rather than full offices. Google is also said to be pulling out of Bermuda, which will lose its utility once the Double Irish is impossible.

Low tax rates will always be an easy incentive to draw corporate investment, particularly as technology corporations become more global than ever. But the danger is that promoting tax-dodging is a race to the bottom where countries compete for businesses just as American cities offer massive tax-incentives to companies building new offices or factories. The tax break offered to Twitter in San Francisco, for example, has become a controversial lightning rod in that city’s struggle with gentrification.

The payoff of offering tax incentives or loopholes is too good for it to disappear entirely, however much we might hope that Apple or Google simply be forced to pay all their taxes in the U.S. In fact, even as Ireland shuts down its most visible tax-dodge, other possibilities are opening up. The “knowledge box” is a new incentive for locating intellectual property like patents in Ireland; the assets would be taxed at a very favorable 6.25 percent.

Britain and the Netherlands already have similar “patent box” policies, but the Irish minister for finance, Michael Noonan, recently said that he wants his country’s intellectual property tax-box to “be best in class and at a low competitive and sustainable tax rate.”