When sports stories wind up in the headlines and network news, something’s usually very wrong. The news business, whether print or television, usually keeps athletes confined in the sports section. So now we have the network anchors talking about Adrian Peterson leaving welts on the flesh of his son, age four, or showing us the video of Ray Rice coldcocking his fiancee in the elevator. Other National Football League domestic violence stories, previously ignored (no superstar players, no video), are now mentioned since they fit the news theme.

These incidents all suggest that maybe football players are just violent people—men with a streak of violence in their dispositions. This personality trait that allows them to flourish on the field, but too often it gets them in trouble after they leave the stadium.

This is the kind of psychological “kinds of people” explanation that I ask students to avoid or at least question, and to question it with data. Conveniently, we have some data. USA Today has the entire NFL rap sheet, and it looks like a long one—more than 700 arrests since 2000. Nearly 100 arrests for assault, another 85 or so for domestic violence. And those are just the arrests. No doubt many battered wives or girlfriends and many bruised bodies in bars didn’t make it into these statistics. Are football players simply violent people—violent off the field as well as on?

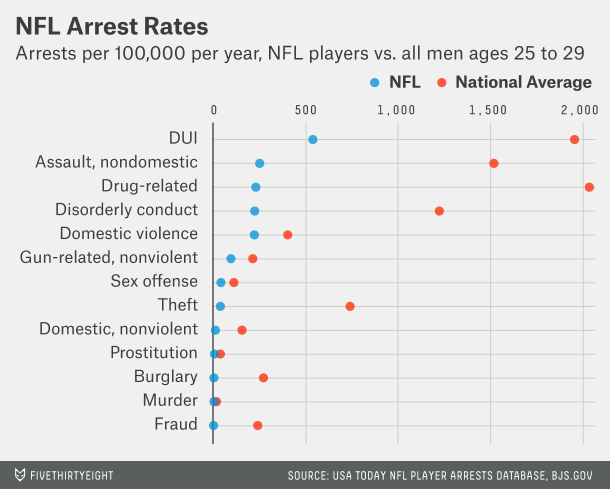

Well, no. The largest category of arrests is drunk driving—potentially very harmful, but not what most people would call violent. And besides, NFL players are arrested at a lower rate than are their uncleated counterparts—men in their late twenties.

This suggests that the violence we see in the stadiums on Sunday is situational (perhaps like the piety and moral rectitude we encounter elsewhere on Sunday). The violence resides not in the players but in the game. On every down, players must be willing to use violence against another person. Few off-the-field situations call for violence, so we shouldn’t be surprised that these same men have a relatively low rate of arrest (low relative to other young men).

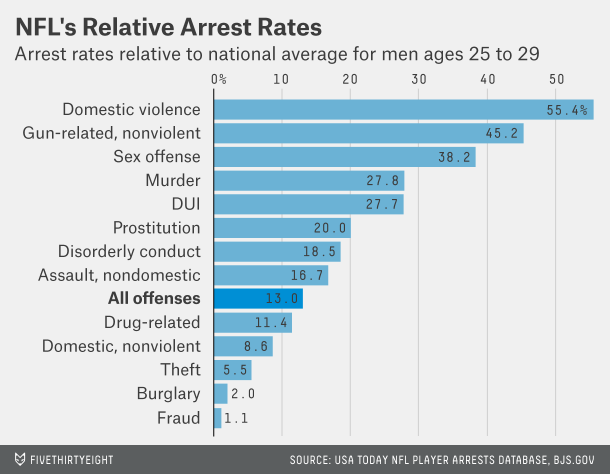

But let’s not discard the personal angle completely. If we look at arrests within the NFL, we see two things that suggest there might be something to this idea that violence, or at least a lack of restraint, might have an individual component as well. First, although NFL arrests are lower for all crimes, they are much, much lower for non-violent offenses like theft. But for domestic violence, the rate is closer that of non-footballers. The NFL rate for domestic violence is still substantially lower than the national average—55 NFL arrests for every 100 among non-NFL men. But for theft, the ratio is one-tenth of that—5.5 NFL arrests per 100 non-NFL. Also on the higher side are other offenses against a person (murder, sex offenses) and offenses that might indicate a careless attitude toward danger—DUI, guns.

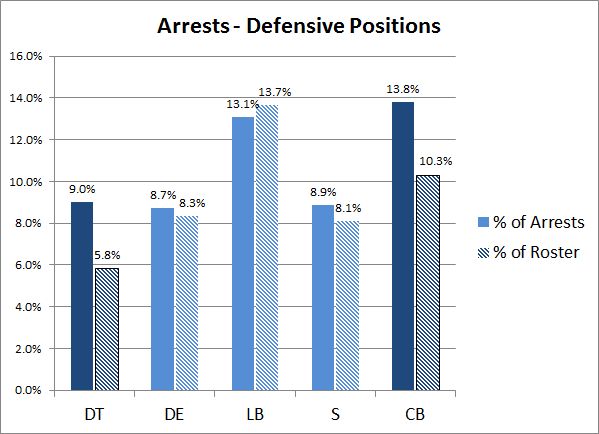

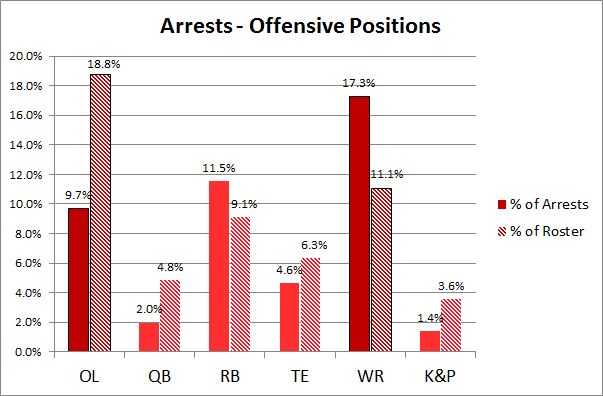

Second, some positions have a disproportionate number of offenders. The graphs below show the percent of all arrests accounted for by each position and also the percent the position represents of the total NFL roster. For example, cornerbacks make up about 10 percent of all players, but they accounted for about 14 percent of all arrests. (The difference is not huge, but it’s something; there would be a very slight overlap in the error bars if my version of Excel made it easy to include them.)

The positions disproportionately likely to be arrested are wide receivers and defensive tackles. Those most under-represented in arrests are the offensive linemen.

This fits with my own image of these positions. The wide-outs seem to have more than their share of free-spirits—players who care little for convention or rules. Some are just oddball amusing, like Chad Ochocinco, formerly of the Cincinnati Bengals. Others are trouble and get traded from team to team despite their abilities, like Terrell Owens of the 49ers, Eagles, Cowboys, Bills, and Bengals.

As for the linemen, the arrest differential down in the trenches also might be expected. Back in the 1970s, a psychiatrist hired by the San Diego Chargers noted this difference on his first visit to the locker room. It wasn’t the players—the offensive and defensive linemen themselves looked about the same (huge, strong guys)—it was their lockers. They were a metaphor for on-the-field play. Defensive linemen charge, push, pull, slap—whatever they can do to knock over opponents, especially the one holding the ball. Their lockers were messy, clothes and equipment thrown about carelessly. Offensive linemen, by contrast, are more restricted. Even on a run play, their movements are carefully coordinated, almost choreographed. Watch a slo-mo of the offensive line on a sweep, and you’ll see legs moving in chorus-line unison. Correspondingly, their lockers were models of organization and restraint.

Maybe these same personal qualities prevail off the field as well. Those offensive linemen get arrested at a rate only half of what we would expect from their numbers in the NFL population. Arrests of defensive linemen and wide receivers are 50 percent more likely than their proportion on the rosters. That can’t be the entire explanation of course. Running counter to this “kinds of people” approach are the other hard-hitting defensive players—defensive ends and linebackers. According to the principle of violent people in violent positions, they should be over-represented in arrest figures just like the defensive tackles and cornerbacks. But they are not.

If this were a journal article, this final paragraph would be where the author calls for more data. But the trend in NFL arrests has been downward, and if fewer arrests means less data but also less domestic violence, that’s fine with me.

This post originally appeared on Sociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner site, as “What Predicts NFL Arrest Records: Position or Disposition?”