The Cazenovia Public Library, in Cazenovia, New York, has everything you’d expect from a small-town library: bright, colorful signs encouraging reading and plenty of inviting chairs. But turn left and head down an unassuming hallway, under a hand-carved sign that reads Wunderkammer (“Wonder Cabinet,” or cabinet of curiosities), and suddenly you’ll find dozens of stuffed birds, a mammoth tooth, a collection of fly-fishing flies, drawers full of fossils, shells, and corals, and a room full of Egyptian antiquities—including a mummy.

Cazenovia’s natural history display isn’t unique, but its kind is endangered. In the last few decades, natural history collections once open to the public have been steadily disappearing. The United States has lost over a hundred herbaria around the country (600 now remain), and institutions tied to public and state funding are in particular peril: The University of Louisiana–Monroe’s natural history museum was eliminated last year to make way for expanded track and field facilities, and the Illinois State Museum was forced to shut down for nine months during a budget standoff in 2016 (since re-opening, its attendance is a fraction of what it had been).

The institutions that tend to survive and thrive are juggernauts in big cities or those supported by well-endowed private universities. Smaller natural history museums like Cazenovia’s, meanwhile, are far rarer, though they still exist: From the Pember Library and Museum in Granville, New York, to the Santa Cruz Museum of Natural History in California, these small museums dot the country, many tracing their origins to the second half of the 19th century, when they were far more common and often represented the only opportunity for many Americans to get hands-on learning about science and nature.

“What I like to tell the kids,” Cazenovia’s Library Director Betsy Kennedy tells me, “is that my grandparents, who were working-class, probably didn’t even make it to New York City in their lifetime.” Yet if these humble rural repositories seem to belong to the past, they’re also of deep interest to researchers, entering a new period of relevance even as they’re disappearing. If we truly are in the midst of a major extinction event, such preserved collections may yet hold clues to our future.

Many of these small museums began with a single individual’s collection—idiosyncratic and often far from exhaustive, they harkened back to the Renaissance idea of the cabinet of curiosities: private collections of natural wonders assembled by wealthy nobility, where the premium was on a widespread and unexpected variety of odd and unusual specimens. The natural history museum that emerged during the 19th century looked similar to these earlier Wunderkammern—displays of different minerals, taxidermied animals, coral, and fossils—but with a very different aim. Instead of jarring juxtapositions, these objects were now arranged not to emphasize their discrepancies, but rather in taxonomical displays that highlighted the hierarchical order of the natural world. A collection reflecting the idiosyncratic taste of a single individual would be augmented over time with a deliberate collection policy to round out the museum.

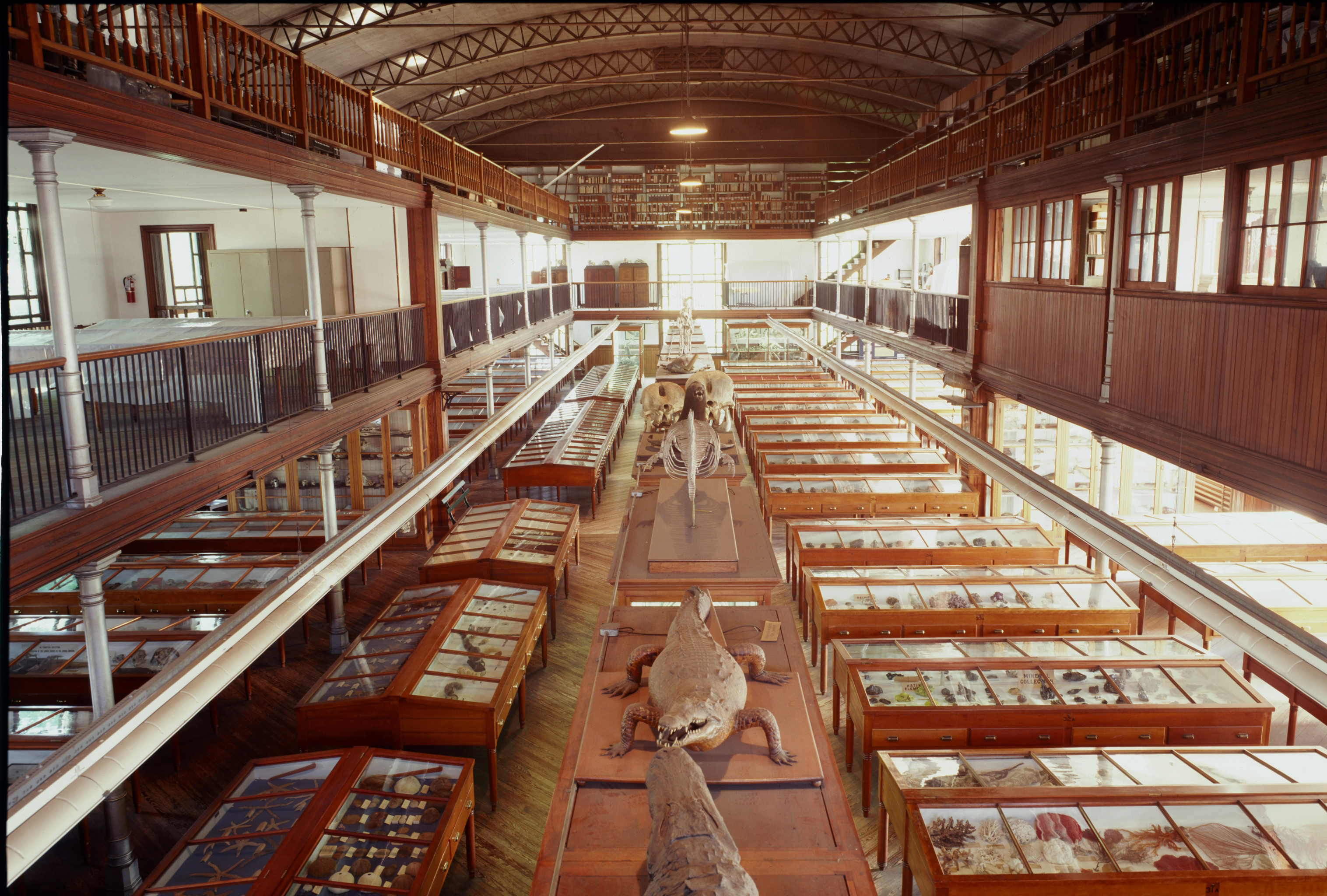

Such was the evolution of the Wagner Free Institute of Science in Philadelphia. Founded by the naturalist William Wagner in 1855, the institute used Wagner’s estimated 30,000-specimen collection (and his library) to further its mission of providing free science courses for Philadelphians. After Wagner’s death, the board appointed internationally renowned biologist Joseph Leidy as the head of its scientific and educational programs; Leidy greatly expanded (but also culled) the number of items in the collection, organizing them by type under endless rows of glassed-in wood cabinets, known as a systematic display.

(Photo: David Graham/The Wagner Free Institute)

This kind of presentation, focusing on taxonomical diversity, was eventually replaced in most natural history museums by dioramas, the kinds of striking displays you can now see at the places like New York’s American Museum of Natural History: a single, often large, example of charismatic megafauna, in a meticulously recreated habitat. Stunning as they are, occasionally scientific accuracy has to be sacrificed for public engagement: The antlers on the moose at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia are actually from a different specimen, as ANS staff members judged the original rack to be too small for such a grand display.

These shifts weren’t just about aesthetic presentation; the very idea of the natural history museum soon found itself threatened. Starting in 1953 with the discovery of DNA’s double helix, the field of biology generally moved away from natural history and whole-animal studies, toward cellular and molecular biology. This turn to the microscopic may be one reason why natural history collections began to suffer. Many smaller museums closed, their collections broken up or discarded; in 1985, Princeton University simply gave away its 24,000 specimen collection of vertebrate paleontology fossils.

We’re gradually recognizing that this was a mistake, and that these once-forlorn collections may contain important DNA evidence. In 2007, realizing that the rise of natural history collections two hundred years ago coincided with a rise in extinction rates among animal populations, researchers in Zurich and San Diego noted that “specimens stored in [natural history collections] often represent the genetic diversity of populations shortly before significant anthropogenic influence,” and argued that, by studying the genetic differences between collections and extant species, “biologists can obtain estimates of the magnitude of anthropogenic influences on population sizes and connectivity (i.e. gene flow between populations), and they can detect cryptic introductions or genetic introgression.” These studies, the researchers conclude, “could guide future conservation action.”

A year after Princeton gave away its fossils, E.O. Wilson noted that “virtually all students of the extinction process agree that biological diversity is in the midst of its sixth great crisis.” The previous five major extinction events, including the most recent, at the end of the Cretaceous period, which wiped out the non-avian dinosaurs among other life, have all been precipitated by natural causes such as plate tectonic shifts or the impacts of bolides or comets. This sixth extinction, however, was, according to Wilson, “precipitated entirely by man.” Biologists have been grappling with what they see as this coming (or perhaps already-arrived) sixth extinction; Terry Glavin, in his 2006 book of that name, writes that a “dark and gathering sameness is upon the world”: a sense that global warming, habitat destruction, and over-exploitation of the Earth’s natural resources are contributing to a massive and coordinated destruction of biodiversity.

(Photo: Colin Dickey)

If it’s true we’re on the verge of a sixth extinction, these collections, assembled at a different time with a different set of concerns, may yet have something to teach us. Susan Glassman, director of the Wagner Free Institute, tells me that, even for species not yet extinct, older specimens preserved in museums may provide additional genetic information useful in documenting their evolution and offering clues to their survival. “There’s a lot of different insights that these kinds of older collections can actually provide,” she says, “like where the specimen was acquired from—because the range may have changed; it may have been obliterated [in a certain place], reflecting climate change or occupational change.”

This is the kind of demographic information that a few key specimens can’t provide in the same way. Indeed, researchers have used museum specimens of the critically endangered red wolf (Canis rufus) to help determine if it is actually a hybrid of the gray wolf and the coyote, or its own taxonomically distinct species—a question crucial in understanding how to protect the scant remaining population. But because even well-preserved specimens may be genetically corrupt (they weren’t originally collected for such genetic work, after all), such studies are best conducted using a broad sample—which means relying on smaller museums alongside major research institutions.

As evolutionary biologist Bryan McLean explains: “A key point here is that every specimen is a unique and irreplaceable record of biodiversity in space and time; moreover, specimens encode and preserve physical properties of organisms such as the genome which can be resampled long after the date they were initially collected.” (McLean’s own research has involved 19th-century specimens from the Smithsonian, and specimens from tiny collections that were gathered a hundred years later in tiny collections.) He also notes that, since we’re constantly reframing our inquiries into nature, it’s short-sighted to assume that only some collections will be of future importance. “When you take this long view of natural history specimens, it becomes clear that all of them are valuable, regardless of the size or the history or even the notoriety of the institution where they are housed.”

While they’re now thinking globally, these little museums continue to act locally. The small museums that have managed to stay alive had done so by focusing on their roots: Rather than worry about being exhaustive or singular, these museums offer a window to a larger world to small-town audiences that might otherwise not ever have the chance.

“We are fairly rural,” says Julia Shotzberger, Cazenovia’s museum educator. “So there are children whose only exposure to a museum is ours—and possibly will be for years to come. It’s not all that common for families to be visiting D.C. or New York City, and if they are going on a family vacation they’re doing Disney World or the Adirondacks. Many families do not make visiting a museum a priority.” Library Director Kennedy also mentions that several museum curators and archeologists have told her that it was the library’s strange collection that first interested them in their careers. Stories like this helped the people of Cazenovia recognize what a vital asset they had, and, after a period of indifference in the 1960s and ’70s, the library was able to raise funds from local citizens, allowing them to move their museum from a dusty single room on the second floor to a new set of rooms downstairs.

In Philadelphia, the Wagner Free Institute had a similar problem, even in the middle of a large, metropolitan city with a robust tourism industry. Overshadowed by the larger Academy of Natural Sciences, and situated in a neighborhood that saw riots in 1964, the Wagner doesn’t attract the same kind of crowds as the ANS. Since the 1990s, however, the institute has increased its budget through fundraising, and broadened its outreach in the immediate vicinity, providing resources for its own low-income community and eventually collaborating with Temple University, only a few blocks away—in effect, mirroring the hyper-local focus of a small-town museum like Cazenovia, even in the midst of a bustling metropolis. The Wagner’s offerings now include (among its many programs) tailored tours for school groups and home-schooled children, a free art and science summer camp, and partnerships with local elementary schools to provide hands-on year-round science learning—along with free adult-education classes on everything from botany to astronomy.

The Wagner’s wood-and-glass cases stretch across a large upstairs gallery, each holding its own page of what was once called the Book of Nature. From fossilized ammonites to a case of primate skeletons, the institute’s 100,000-specimen collection tells a history of the natural world that stretches back millions of years, and across vast taxonomical categories.

Stepping into museums like these can feel like stepping back into some earlier era. Partly, this reflects the reality of funding; William Wagner left his institute with enough of an endowment to stay open and pay for its free classes, but external and unforeseeable factors after his death (such as the changing value of real-estate investments) limited the money available for the kind of grand modernization and revitalization that happened across town at the ANS or in New York. And so the collection has stayed more or less just as it was in the 1880s. If it seems that science and progress has passed it by, that’s because they have.

Such places are a far cry from today’s interactive (and often overactive) displays at the big museums in major cities, with bright, kid-friendly signs and corporate sponsorships—but that’s not a bad thing. A place like the Wagner focuses on the wide variety and display of as many different species as possible. Instead of dioramas displaying them in their natural habitats, the focus is instead on their relationships to one another and the natural world. Glassman shows off one cabinet that contains a pangolin alongside an armadillo—two animals from different families that nonetheless have similar “armored shells”—explaining how Joseph Leidy, in organizing the Wagner, balanced out the displays with this educational goal in mind. This means the Wagner’s displays often include both typical, everyday species (foxes, herons, horses), and more rare creatures: “Not the exotic for exoticism’s sake,” Glassman says, “but for understanding the principles of their niche, these animals that had a highly specific adaptations, whether they are morphological, or diet, or habitat or whatever. It was very carefully chosen, so that you saw representative animals and things you were familiar with, and then things you were less familiar with that could teach certain principles.”

The Cazenovia Public Library has divided its collection into two halves: the “museum” and “the cabinet of curiosity,” the latter of which refers to an interactive display on the history of Wunderkammern, designed by Pat Hill and Patricia Christakos, built around a large case carefully crammed with coral, fossils, local historical ephemera, Native American artworks, a dinosaur egg, and a taxidermied squirrel. It offers a hands-on portal to a forgotten kind of museum. Children are invited to open the drawers below the display, each of which holds more treasures to explore. “One of the coolest things,” Kennedy says, happened about a week after the exhibit opened. Two 11-year-old boys, lost in the wonders of the cabinet, were using a smartphone to look up and identify each of the specimens in the various drawers. “They were here like 40, 45 minutes,” Kennedy remembers. “For 11-year-old boys, that’s pretty good!”

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.