Amazon and its founder Jeff Bezos have recently been dominating the headlines even more than usual. Last month, Amazon became the most valuable company in the United States, valued at $797 billion. As of this writing, Bezos is the richest person in the world, his net worth estimated at $112 billion.

There’s an American obsession with start-up stories; like a lot of other famous tech billionaires, Bezos began in his garage, where he founded Amazon in 1994. This tale conforms to the American mythos of the entrepreneur—the visionary striking out on his own to create a business that changes the world while enormously enriching himself (and these figures are almost always male). But it’s worth asking: How is it possible for one man to earn $112 billion in just 25 years? Where exactly does all that money come from?

Believers in the entrepreneur mythos would argue that a combination of brilliance, innovation, determination, and strategic risk-taking will pay dividends—occasionally a hundred-billion-fold. Another economic theory, Karl Marx’s concept of surplus value, pushes beyond such a rose-tinted view and explains that Bezos is so rich precisely because his workers are so poor.

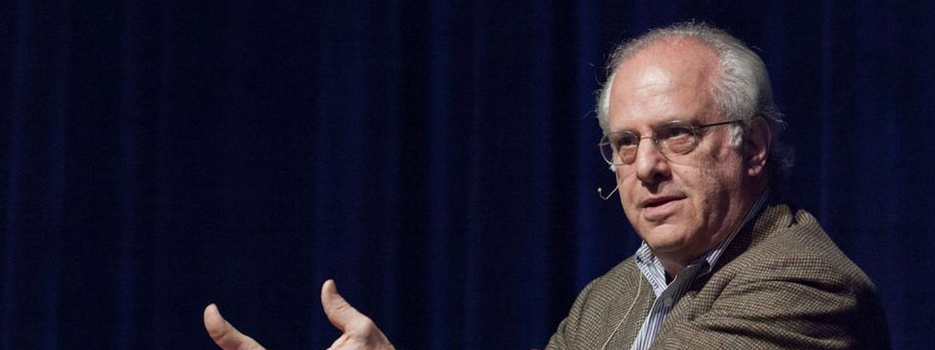

“Marx points out—he does it both theoretically and empirically—that workers who add value while they work are paid a wage that is less in value than the value they add while they’re working,” explains Richard D. Wolff, professor emeritus of economics at the University of Massachusetts–Amherst and currently a visiting professor in the graduate program in international affairs at the New School.

Crudely put, the theory of surplus value explains that employers take the wealth created by their employees and “skim off the top.” In this account, all the revenue that a business takes in is produced by its employees, who manufacture the company’s wares and/or provide its services. That revenue, minus the expense of raw materials, tools, utilities, etc., equals the value that the employees have created using those raw materials, tools, utilities, etc. Rather than receiving the full value of their work, though, employees are given only a relatively small proportion of it as wages, while the employer keeps the rest. It’s a zero-sum game: The more value paid out to employees in wages, the less value remains for employers to retain as profit.

(Photo: Richard D. Wolff)

In Amazon’s case, Wolff says, the wage-to-profit distribution is less Bezos skimming off the top and more him leaving workers the dregs.

“You have literally got hundreds of thousands of employees of Amazon who are adding value as they work,” Wolff says. “The value added by those workers is greater than the value paid to them as wages, and that’s the surplus value that is accruing, in a capitalist system, to the employer.”

During the third quarter of 2018, Amazon made nearly $1 billion a month in profit. Were it distributed equally between its roughly 500,000 employees, each employee would earn an extra $2,000 a month. That’s quite the bonus, considering that most Amazon employees, if they work full time, earn a little more than $2,400 a month even after their recently hard-won fight for $15 an hour.

Instead, that $1 billion-a-month profit goes to Amazon leadership and gets distributed according to the whim of its board of directors—of which Bezos is the chairman. This allows him considerable influence in pushing for reinvestment in the company. Reinvesting so aggressively and consistently means Amazon is now in a position to build a second headquarters, conduct further research and development, and hire more workers, but it also makes the company itself more valuable—and, because Bezos still owns 16 percent of it, lines the pockets of its founder-chairman. This is where Amazon’s $131 billion in assets come from, which drive its $797 billion valuation and Bezos’ $112 billion net worth.

It doesn’t end there. As Wolff points out, far from giving Amazon employees their fair share, Bezos has, in fact, shorted his workers so severely that taxpayers are forced to make up some of the difference.

“Amazon is famous for having offices and officers in various of its workplaces that help workers qualify, fill out the forms, and learn about government programs they’re entitled to,” Wolff explains. “That’s just Amazon’s way of improving their surplus—by getting the government to pick up the cost of the laborer.”

Prior to the “Fight for $15,” the wages that Amazon offered its employees were so low that many qualified for government assistance. For example, according to a 2017 survey of its employees in three different states, anywhere from one in 10 to one in three Amazon employees relied on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, more commonly known as food stamps. Put another way, Amazon has denied its workers so much of the wealth they create that taxpayers have been necessary to keep those employees alive.

Skimming $1 billion a month in surplus value from your employees and at least $13 million a month from the public (not to mention billions more in tax breaks)—that’s how one man “earns” $112 billion, according to the theory of surplus value: It’s at the expense of the rest of us.

“Beyond all of these analytics, there really is an almost moral or ethical question here that ought not to be missed,” Wolff says. “How you spend that kind of money shapes tens of millions of peoples’ jobs and incomes and standards of living,” he continues, referring to Bezos’ personal fortune. “It’s determining families who can’t give their children—because they get a low Amazon warehouse wage—can’t give them half the breaks in life that they need to be successful, can’t pay for their educations, can’t pay for the health care they need.”

“It’s outrageous, in a society that claims to be democratic, to say that there’s a person who has that much power over all the basics of society compared to everybody else.”

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.