Is a city council with five white members and one black member diverse? Considering the current debates on racial representation in politics and policing in Ferguson, Missouri, it’s a sensitive question.

The answer, researchers find, depends not only on if you are white or a minority race, but which minority race you belong to.

If a team did not contain at least one member of their own racial group, the participants considered it less racially diverse. This “in-group representation effect” was stronger for blacks than for Asian Americans.

A group of researchers, led by Christopher Bauman of University of California-Irvine, wanted to tease apart the meaning of “diversity” beyond the naïve, generalized notion of racial heterogeneity. In three experiments, subjects were presented with headshots of a company’s management team and asked to rate how “ethnically diverse” each team was. The results, published this month in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, suggest that people are more likely to think a group is diverse if that group includes members of his or her own race.

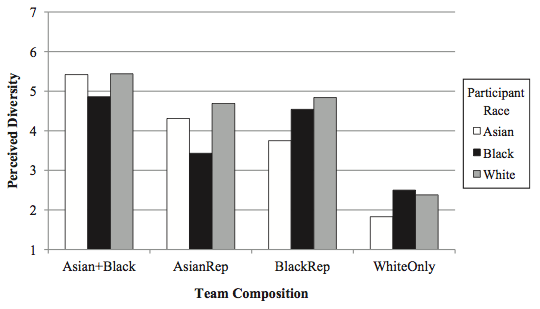

In the first study, 1,899 participants ages 18 to 91 viewed headshots of six people in business attire. The “white only” team featured six white headshots, the “black rep” team had four white and two black people, the “Asian rep” team had four white and two Asian people, while the “Asian + Black” team had four white, one black, and one Asian person.

Results showed that black people thought the “Asian rep” team was less diverse than other teams (except “white only”), and Asian people thought the “black rep” team was less diverse than other teams (except “white only”). In other words, if a team did not contain at least one member of their own racial group, the participants considered it less racially diverse. This “in-group representation effect” was stronger for blacks than for Asian Americans.

The effect, researchers say, is due to people’s experience with racial discrimination. People expect that a group without a member of their own race may be more likely to discriminate against them. This could explain why blacks show such a large effect—in America, blacks face more discrimination and prejudice (and think about it more often) than Asians.

After reading about how the other minority group suffers from prejudice, the in-group representation effect disappeared.

In a second study with 1,080 participants, researchers attempted to manipulate the effect by having participants read news articles about the prevalence of prejudice. When one minority race read an article about prejudice against the other minority race, the “in-group representation effect” disappeared. In other words, after reading about how the other minority group suffers from prejudice, a person would judge the “black rep” and “Asian rep” groups to be equally diverse, regardless of his or her race.

This is one of the few papers on how diversity is perceived among minorities, so more research is needed, especially to measure the perceptions of other minority groups. Other variables could also play a role—for instance, the number and institutional rank of minority group members in leadership positions.

What these studies do show is that “policies that monitor the overall number of minority group members” are not enough, researchers write. “Diversity is too complex for any one-size-fits-all solution.”