Kara Walker’s recent site installation, “A Subtlety or the Marvelous Sugar Baby: An Homage to the Unpaid and Overworked Artisans Who Have Refined Our Sweet Tastes From the Cane Fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the Demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant,” evokes a collective—that of the laborers who produced the capital frameworks for our nation, and largely remain economically outside of it. It is a mythological female form through which the artist asks us to contextualize our roots in slavery, in exploitation of female labor and body, in market and consumption. On Instagram and in other social media spaces, selfies taken with “A Subtlety” in the background have proliferated. Such usage of the installation as a prop, in front of which visitors make “funny” and obscene gestures, has generated a fairamountof critique. The critiques focus on the ways in which the spectators remain oblivious to the history of enslavement and abuse at work in Walker’s art; instead, they turn it into a cheap source of titillation and amusement. What many of the critiques fail to point out, though, is that this isn’t a new phenomenon; since the 1830s, white American consumers have turned black and brown bodies into entertainment.

Recent scholarship—such as Eric Ames’ Carl Hagenbeck’s Empire of Entertainments on the American circus, and Vivek Bald’s Bengali Harlem on the early 20th-century Indian communities in New York—allows us to understand the historical contexts which produced and populated the spaces where American consumers became spectators of the Orient.

Walker’s attempt at confronting spectators with a grotesque body engaged with only one aspect of the history of black and brown bodies in America: It highlighted the deep roots of female labor in sugar plantations and refineries.

The earliest form of tent-circus, containing performing animals, stuntmen, clairvoyants, and magicians, was common in the late 18th century. Starting in the 1830s, P.T. Barnum introduced the “Grand Ethnological Congress”; a decade later, it featured “freaks,” “monstrosities” for public gawking and admiration. The popular racial and civilizational understanding of Darwin’s evolutionary thesis contributed to the dehumanizing of the enslaved black body and the aboriginal body. The female body was specifically put on display to meet the crowd’s voyeuristic demands. A well-known example is Joice Heth who in 1835 was presented as George Washington’s 161-year-old nanny. Barnum circulated stories that she was an “automaton made from foam” and he charged people to come and touch her to authenticate or refute these stories. After her death, Heth was autopsied and put on display in Barnum’s American Museum in New York.

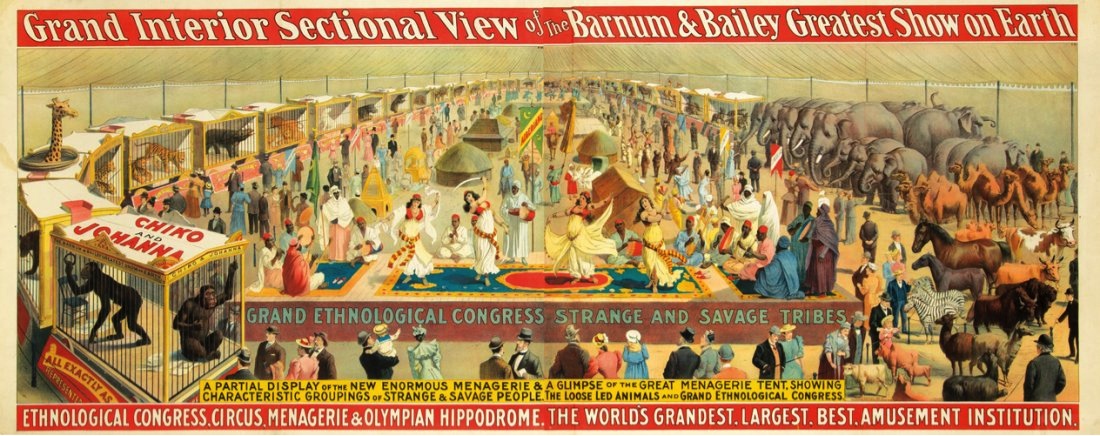

By the 1840s, circus shows such as Barnum’s depended on presenting to an ever growing circle of white American viewers “exotic” people from “lost races.” The circus played a crucial role in the expansion of industry, capital, and railroad across the Western lands, and the displacement and disintegration of Native American lives and communities. In 1890s, Barnum & Bailey was producing giant tent spectacles based on Arab and “Moorish” themes. In 1892, at the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ “discovery,” a “Grand Ethnological Congress,” composed of “Berbers and bedoiuns,” “Oriental Indians,” “wildmen,” “Zulu,” and “Tribal Chiefs,” was assembled by Barnum & Bailey. The show poster demonstrated a range of performing brown and black bodies, along with animals, arrayed for display.

Such displays were a part of nearly every large circus show, and were specifically featured at several World Fairs, including the Chicago Columbian Exhibition of 1893 and the St. Louis Exhibition of 1904. From the colonized worlds of South and Southeast Asia, North Africa, West Africa, Arabia, and East Asia, communities of people—purchased—were displayed to the industrious white families of American cities. A forgotten example is the case of Appoo Hamid, who, the New York Times reported, was a “freak from India” imported for Barnum & Bailey’s Great Show. The report, from March 28, 1896, describes him as follows:

“Some difficulty, too, was experienced with Appoo Hamid, the dwarf, who is said to represent the lowest type of the human race yet discovered. He is about 28 inches high, and is not particularly attractive. He has just passed his thirtieth birthday.”

The “Indian curiosities” were housed at 115 West 27th Street and “a crowd collected around the house” which the “police had to clear,” according to the New York Times. Hamid, the report says, was “the only dwarf of the Indian type ever sent to America. Several ethnologists have pronounced him to be the nearest thing to a baboon yet discovered. He clung very closely to the steam radiator yesterday, putting his arms around it. There is practically no bridge to his nose, and it is seldom that a gleam of intelligence lights up his countenance.”

In the report, there is a distinct and deliberate—and disturbing—racial and civilizational contextualization of Hamid that is created for the spectacle he is promised to offer. The illustration that accompanies the report—Hamid is shown naked from the waist up, with his hands at his side, a dull countenance on his face—makes this case most clearly. Compare the illustration to the description the report provides of his arrival to the house: “The dwarf emerged from the couch clad in a pair of golf stockings and a smoking jacket. He chewed gum violently.” The unclothed individual is a spectacle purchased by Barnum & Bailey’s Great Show, not an angry human who was sold into bonded labor.

There is scant information available about Appoo Hamid but newspapers did report on his presence at the St. Louis Exposition in 1906 and published a short note that he committed suicide in 1908.

Hamid’s immigrant experience was duplicated by Ota Benga, who was brought to New York from the Congo in 1906 by businessman Samuel Verner as an example of an African pygmy. He was placed at the Bronx Zoological Gardens (now the Bronx Zoo) and put on display in the monkey house. The New York Times gleefully reported that if he had not been “rescued” by Verner, Benga would have been eaten by his own people. The depiction of Ota Benga as either a cannibal or an animal were made through illustrations and photographs accompanying reports—either with sharpened teeth, or carrying a monkey. Benga rested uneasily in the Bronx Zoo and was soon sold to a circus and displayed at the St. Louis Exposition in 1904. He was later released into a Colored Orphan Asylum, where he lived for 10 years before committing suicide.

Kara Walker’s attempt at confronting spectators with a grotesque body engaged with only one aspect of the history of black and brown bodies in America: It highlighted the deep roots of female labor in sugar plantations and refineries. What it left out was that brown and black bodies were not just used on farms, plantations, and factory floors; they were also trumped up in orientalist and racist garbs (“Sphinx” like) and put on display for entertainment. The lost histories of Appoo Hamid and Ota Benga document the abuses of social spectacle in American past. Their lives were made remarkable by spectacle alone. They were forced to play a role in a cultural and political conversation that imprisoned them, stripped them of their humanity, and displayed them.

The prospect of gawking, exclaiming, and comparing our bodies to others that created the spectacle of the late 19th and early 20th century remains a pivotal part of the framing of black and brown bodies in contemporary America. We can trace its contours in the dehumanized prison populations, in the rhetoric of legality attached to refugees and migrants, and in the surveillance enacted upon specific faiths. Yet the community of spectators, which creates the spectacle, remains un-critically hidden. We are all looking at “A Subtlety,” but in some ways, we should be looking at ourselves.