I have a pretty pair of black Everlasts, but I take the loaners whenever I go to a new gym. I want the other guy’s damp history, to imprint the DNA of the place into my skin. It’s one of my superstitions, like tapping twice and hard on any handmade motivational sign—as long as there’s nobody around to catch me, casting my little spells like: Please let me pass through this place, unnoticed but for the man I am.

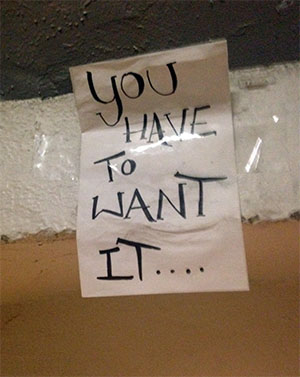

I bang-banged “You have to want it” in the stairwell of this sweaty basement spot downtown, which looked like every other “authentic” boxing gym I’ve been in: prizefight posters papered the walls; speed bags lined the ring’s perimeter along with an uneasy mix of pasty, well-coiffed brokers and grizzled, broken-teeth ex-pros and hungry, ripped amateurs. They all jockeyed for space, careful not to touch, every shoulder bump a possible brushfire. An older guy with a dent in his forehead pushed past me and called “Sorry” behind him not once but three times, hands up, and I felt his fear of me, how it ran between us, electric.

I love boxing gyms like I l love barbershops and vaguely antiquated, highly illuminating conversations with friends’ dads about dating etiquette. “You’re having a romance with masculinity,” my friend, a boxing fan, told me. “And the thing is: love is dark, too.”

It’s ugly, like how I gave myself a shot this week and nicked a blood vessel. The spray of blood on my hardwood floors was not a metaphor but my body astonished, my body alive.

When I started taking testosterone, I was 120 pounds and all angles. Twenty pounds and three years later, I know when to step toward a threat and when to walk away. I know that I think about violence, that I hate it but move now in a world defined by power in ways I didn’t choose and don’t want. All the meditation and good intentions in my heart cannot cut down the alpha in the office meeting or the guy following me down the street, looking for a fight. I never stop trying to be the kind of man who uses privilege and power for good, but then again here I am: left jab, left jab, right cross; right cross, right cross, left jab. Here I am, pretending that this punching bag is the head of this truly terrible dude I know—an abusive sociopath who ghosts my life daily.

I want to say that I don’t love this part of me, this edge. I want to find my hot desire to give this guy stitches disturbing, but I can’t, I don’t. I want to say I wouldn’t fight dirty if I found myself alone with him in some Midtown alley, but I know myself and I would. He’s a menace to a woman I love, so of course I’d get him in a chokehold if I could, I know myself: I’d whisper vigilante, horrible little horrors in his ear and I wouldn’t regret a second of it.

MOST VIOLENCE HAPPENS AT the hands of men. Men beat women, men rape, men torture. Men use power to keep women and children silent, men kidnap, men kill. Men walk into movie theaters and schools and shoot people for no reason, men blow up buildings, men murder trans women and leave them by the side of the road in San Francisco.

Men betray our partners: Over a third of women globally experience physical or sexual violence at the hands of a boyfriend or husband; nearly 40 percent of women killed worldwide are murdered by an intimate partner.

Men, like my father, molest children.

Men, like the man who almost killed me on an Oakland sidewalk in 2010, shoot other men over nothing.

When I injected my first shot, when I first walked into a truck stop bathroom with ease, I realized that my body allowed for a dark trade: I could stroll dark streets late at night and each man I encountered was the worst kind of threat but more likely an animal giving me a wide swath. But I, in turn, had become a potential danger: women crossed the street regularly to avoid me and my beard. It was nearly instant, the way I became part of a lineage that is, in some ways, a cancer on half the world.

Of course, the other truth is that I fought hard to be who I am: one man, a good man, a beating heart in this skin. If I’m honest, it’s too easy to leave it there. The truth is, I hit a punching bag and pretend it’s this shithead. Why? I refuse to blame the hormones or the socialization or to ignore them; I won’t have the romance run the game without questioning the game itself.

Especially when the game holds the shadowy metaphor in its most naked, sweaty form. Joyce Carol Oates, boxing fan, wrote in On Boxing, the best book on the subject, that it is our “our most dramatically ‘masculine sport.”

I get it, and it breaks my heart.

My romance with masculinity is beauty and terror. It’s like watching a match where the guy rises, zombie-like, and hits his opponent again and again with autopilot eyes—I am transfixed, I am horrified, I am not him and I am. I watch a match where a guy won’t get off the mat and I feel his humiliation, his wounding in that final count, his desire to live greater than his pride—and I feel my stomach turn at a world where his survival isn’t a victory but a failure.

My world now.

Oates quotes her friend, a sportswriter and boxing fan, in her book: “‘It’s all a bit like bad love—putting up with pain, waiting for the sequel to the last good moment. And like bad love, there comes the point of being worn out, where the reward of the good moment doesn’t seem worth all the trouble.’”

I transitioned because, for me, there was no alternative: I was against the ropes. Maybe that’s hard to understand, but I suspect for most of us there’s a blistering, bitter reality best captured in the grace of a perfect uppercut. It is a truth about love, about masculinity, about moving through this violent, horrible, magical world that we might not want to see but at what cost?

“We don’t give up on boxing, it isn’t that easy,” Oates writes. “Perhaps it’s like tasting blood. Or, more discreetly put, love comingled with hate is more powerful than love. Or hate.”

It’s ugly, like how I gave myself a shot this week and nicked a blood vessel. The spray of blood on my hardwood floors was not a metaphor but my body astonished, my body alive. I got on my knees and mopped it up with paper towels and felt afraid and proud and alone. No one but you knows this. Every day is a paradox: I pass and I remain a man apart; I appear to be what I reject; I am one of you, I am not.

FIST FIGHTING IS ARGUABLY the most political of all sports. From death matches between Roman slaves to the powerfully symbolic 1971 Ali-Frazier Civil Rights-era “Fight of the Century,” boxing has a long and brutal history of pinpointing the larger power dynamics undergirding culture.

We are in this system, we are here for our own private reasons, we are each others’ enemies and allies, we carry the history of every one who looks like us, we pass and we either own it or we don’t.

Maybe that’s what ties the tech bros and the muscled teens with the fade and the ponytailed powerhouse woman together in this spot, down near Wall Street, that is both an approximation of some ancient masculine bastion and a relic of one at once. Among the Tyson posters and aging white guys with bad form shadowboxing mirrors and compact kids with no body fat and shitty headphones hitting speedbags with a rhythmic hiss, we are all fighting something or someone. We are in this system, we are here for our own private reasons, we are each others’ enemies and allies, we carry the history of every one who looks like us, we pass and we either own it or we don’t.

“FIGHTING SOLVES EVERYTHING,” READS the back of my instructor’s shirt.

He keeps touching my gloves, gently, pushing my hands up to my face. His body is a machine of muscle and tendons, wiry and insane looking, but his voice is soft, encouraging. “Elbows in, chin up,” he says, like a prayer.

He points to the masking tape on my bag. “Right hook, full power now,” he says. “That X is a forehead, that X is your worst enemy, hit that X, hit that X, hit that X.”

If I am honest I will say that I feel that tingle in my teeth and my fingertips when I think about breaking that abusive guy’s jaw, I want him to come to a violent end, I want to see him on his knees and I want to be the one who put him there. Because I love someone he has wounded, I am a lion. My tenderness is fierce, it balloons my shoulders and biceps, pushing my arms out like wings, my chest forward. I step in. It is a care like I’ve never felt before, it is knuckles and split lips and simple rules like don’t scream at this woman I love, not now not ever.

IT’S IMPOSSIBLE TO TALK about boxing without talking about class.

It’s impossible to talk about passing without noticing that, despite the hand tattoos, I see myself shadowboxing in the mirror and I know who I appear to be: the white guy in his early 30s with the sharp haircut and the weak left jab. I know that the old guys brush past me on purpose, that I don’t belong here, but that I don’t belong anywhere else, either. This is a safer version of a world I will never understand. I might be self-made, I might not have a trust fund or a safety net, but I’ve never put my body on the line for a $500 purse.

We ended the night with hundreds of crunches, sadistic drills that went on for so long I left my body. I’m sure we all did—us 20 headbanded professionals getting our cardio in. As my vision blurred all I could hear was this guy behind me, a real boxer with a fucked-up nose, going at a bag harder than I ever could. With each punch he made this strange sound, a cross between a cough and a laugh, dancing around my head expertly in his wrestling boots. It became a kind of trance, all of our bodies and the instructor yelling “Don’t stop, don’t stop, don’t stop” and the dude looking really wild in his eyes, hitting that bag like it had done him wrong—it wasn’t simple or moral but it was transcendent.

Later, the locker room was full but dead silent as we hustled in tandem, unlacing boots and unwrapping hands and unbiting mouth guards. I pulled off my shorts and regretted the pink stripes on my boxer briefs, the fact of my difference, the fear that someone might notice that I’m not the man I seem to be as I tried to casually throw on my jeans. But then I slowed up, eyeing the sign on the stall: “If you punch this toilet, we will knock you out.” I put on my pants one leg at a time, like a man who’d never be anything less than intentional, like a man without shame, like a man who knows he has nothing to hide.

The American Man is a semi-regular series from Thomas Page McBee that features gonzo reporting from barbersshops, boxing gyms, frat houses, and other bastions of masculinity in an effort to define what makes a modern man.