As insect-infecting bacteria go, the Wolbachia genus has been shaping up to be particularly nifty when it comes to fighting mosquito-borne diseases. When Wolbachia strains infect Anopheles mosquitoes, they have been shown to provide their insect hosts with immunity to malaria parasites. Researchers also hold high hopes that the bacteria could be used to control Dengue fever and other viruses and parasites that are spread by biting insects.

But buzz-killing new research has revealed the potential dangers of releasing certain mosquitoes infected with Wolbachia into the wild.

The deliberate release of infected mosquitoes could provide lasting protection against malaria while reducing the need for harmful pesticides.

Jason Rasgon, an associate professor in Penn State’s entomology department, has been investigating Wolbachia and mosquitoes for more than a decade. He recently tested whether the bacteria could help control the spread of West Nile Virus by Culex mosquitoes. The species, Cx. tarsalis, is also responsible for the spread of St. Louis encephalitis virus and the Western equine encephalitis virus across the Western United States.

Rasgon’s team took a laboratory strain of mosquitoes that was originally captured in California’s Yolo County. They knocked young female mosquitoes unconscious using carbon dioxide and then injected some of them with Wolbachia and others with a control substance. A week later they were fed cow blood infected with West Nile. One and two weeks after the feeding, mosquitoes were killed and tested for the disease.

The results of the experiments came as disappointment. “We had to repeat it a couple times before we actually believed the result,” Rasgon says. “We were expecting this to block West Nile.”

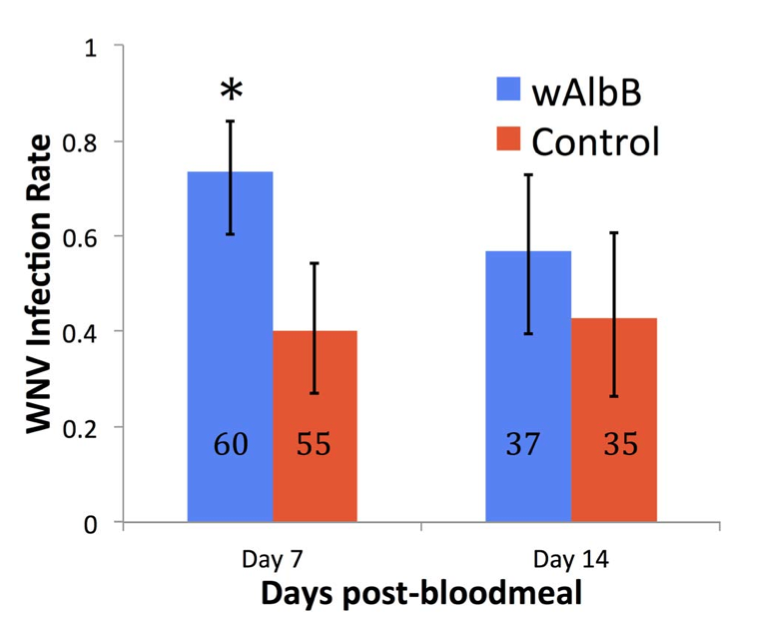

The following chart from the paper, published Thursday in PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, shows that mosquitoes treated with the wAlbB strain of Wolbachia were more likely to carry the virus that the researchers were trying to protect them from. The asterisk denotes statistical significance:

(Chart: PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases)

“This is the first time a human pathogen has been shown to be enhanced with a Wolbachia infection,” Rasgon says.

During similar experiments, the expression of a gene involved with immune protections was modestly, albeit statistically significantly, lowered in Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes.

Wolbachia bacteria often infect insects’ reproductive tissues, where they can improve the chances that their invertebrate hosts will reproduce—sometimes eliminating the need for mating altogether. It helps the bacteria pass through eggs from one generation to the next. That means the deliberate release of infected mosquitoes could provide lasting protection against malaria while reducing the need for harmful pesticides. Field trials in Australia several years ago established a strain of Wolbachia inside a wild population of Aedes mosquitoes that could help bring down rates of Dengue fever.

But it also means that any dangerous side-effects could be cast in tiny reproductive stone for generations to come after infected specimens are released. Rasgon says the findings show the need for caution in moving forward with Wolbachia-based mosquito control efforts.

“I can’t believe this is just a fluke,” he says. “If you keep looking, you’ll probably find more examples of it.”