Climate negotiators in 2009 agreed upon an unpalatable goal: to produce a 2015 climate treaty that caps global warming at two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. That’s more than twice the amount of warming so far, which is already leading to more powerful storms, worse heat waves, and less predictable monsoons and cold snaps.

But global efforts to revolutionize the world’s energy supply and slow down climate change are way off track when it comes to meeting this arguably unambitious goal.

However, new research suggests that not much more investment would be required to meet the goal than the amount of public money that governments worldwide already spend every year on climate-harming subsidies for fossil fuel companies.

“Technologically, there’s no reason we can’t rise to the challenge. It’s more a question of politics, and that appears to present a major challenge in every country, even in the more progressive countries of the world.”

The findings, published in Climate Change Economics, suggest that $1.1 trillion would need to be invested every year, on average, in clean energy between 2010 and 2050 to meet the goal. Already some $300 billion is being spent annually, meaning there is presently a “clean-energy investment gap” of about $800 billion a year.

That’s obviously a ton of money. But about $1 trillion is already being invested on energy projects every year worldwide. And compare the size of the investment gap with the $500 billion or more being doled out every year in the form of government subsidies that help support fossil fuel operations.

“The total investment effort doesn’t need to increase too dramatically,” says David McCollum, a research scholar focused on energy at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis in Austria. McCollum collaborated with seven other researchers from Europe and the United States to analyze climate and economic models to project the levels of low-carbon energy and efficiency investment that would be required to slow greenhouse gas emissions to the point where global temperature rise would stay within the boundaries of the two-degree goal.

“We can say that the magnitude of the clean-energy investment challenge is roughly similar to today’s fossil fuel subsidies,” McCollum says. “However, it’s not as simple as just diverting the money from fossil subsidies over to clean-energy technologies. That’s because fossil subsidies tend to be concentrated in some major fossil exporting and producing nations, as well as some in some major energy consumers. Investments into clean energy will be needed in every country in the world.”

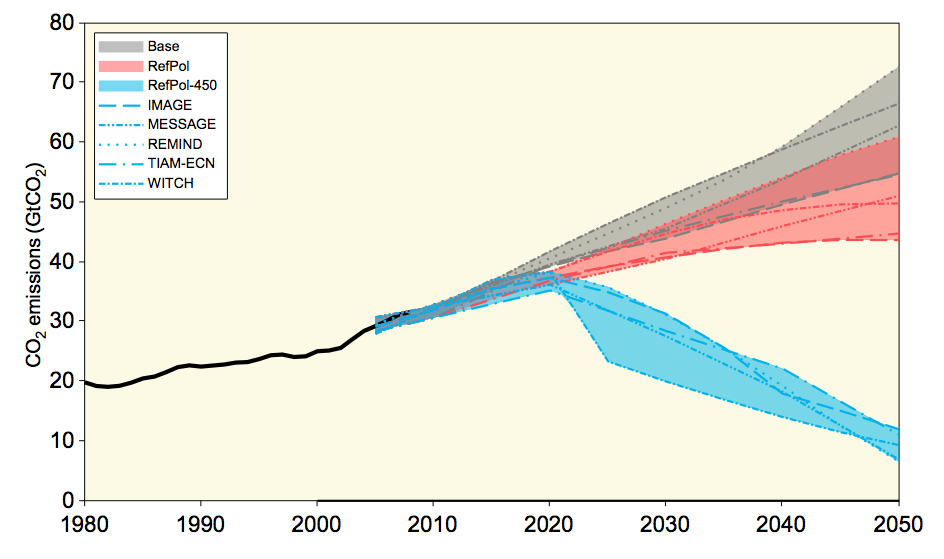

To meet the two-degree goal, around 900 gigatons less global carbon dioxide and equivalent pollution would need to be released this century than would have been the case if no action were taken. In this graph from the new paper, gray shading shows pollution levels forecast by different models if there were no clean-energy investment. The red shows projected emissions under the current $200 to $250 billion a year in clean-energy investments, rising to a planned $400 billion. Blue shows how emissions would fall to needed levels if the investment gap closed.

“Technologically, there’s no reason we can’t rise to the challenge,” McCollum says. “It’s more a question of politics, and that appears to present a major challenge in every country, even in the more progressive countries of the world.”