Kisvárda, Hungary, 1954. The summer night was warm, the road outside deserted. No one drove any more unless they were secret police or favored by the Party. Inside, Irén and János Vargha sat watching their two-year-old son’s eyelids as he slept through his fever. The only visible sign of the attack, they were told, would be if György’s eyeballs started moving rapidly.

Polio was unpredictable. Often no more harmful than any other childhood infection, it could on occasion “turn” with swift, inexplicable savagery, destroying a child’s nerve cells and leaving him paralyzed for life. If it damaged the nerves controlling his lungs they could freeze up and György would either die or spend the rest of his life inside an iron lung that breathed for him.

The hours crept by without him showing any symptoms of paralytic polio, but the next morning, as Irén stood him on the table to get him dressed, his legs buckled. She stood him up again—again his legs wouldn’t support him. This moment is his earliest childhood memory. “I could stand easily before,” he says. “Now I could still bend my legs but I couldn’t straighten them. For me it was astonishing and interesting that my legs were doing that strange thing. But my mother was afraid.”

György was rushed 100km to the hospital in Debrecen. Then began the frantic search for gamma globulin. The antibody-rich solution was the only medicine then known to have some ability to disarm the poliovirus in the bloodstream, preventing it from invading the nerves. But gamma globulin was scarce. Irén and János rode from town to town and village to village on their motorbike, pharmacist after pharmacist regretfully shaking their heads.

Later that evening, as they sat at home thinking of their son fighting his lonely battle in a strange bed far away, there was a knock at the window. Behind the curtain they saw two ávós—secret police agents—waiting at the door, a large black Pobeda parked in the empty road behind them. In 1950s communist Hungary, when a black car stopped outside your house in the middle of the night, there was only one explanation: The ávós had come to take you away.

The secluded location meant that polio-stricken bodies—the antithesis of the ideal, healthy proletarian body—were largely out of sight.

But when János and Irén opened the door, fear gave way to relief, then bafflement. The men explained they had driven three-and-a-half hours from Budapest because they had heard the Varghas’ son had polio. They were very sorry and had brought the boy some gamma globulin.

Sixty years on, György’s daughter, historian Dr. Dora Vargha, tells me her father’s story over coffee in Bambi Presszó on the Buda side of the Danube. Her own little boy is three years old, a little older than György was when he first caught polio. Her son was born just as she was starting to write up her research, the first ever history of polio in Cold War Hungary. “It put everything in a different place. I could suddenly feel the stakes—the fear. I took him for his first polio vaccination just after I finished my research. That was a strong moment for me.”

We’re just down the street from the National Institute of Rheumatology and Physiotherapy (ORFI), where György spent a large part of his childhood. Sadly, the ávós delivery arrived a little too late for the young György, who needed six operations on his legs and rehabilitative therapy in the Lukács Thermal Baths opposite the ORFI.

In communist Hungary, both the café and the baths were favorite haunts of intellectuals and dissidents, who exchanged ideas in the haze drifting over ashtrays or rising from sulfurous, shadowy thermal waters. The tradition began at the end of the 19th century, when Budapest’s new middle class constructed elegant bridges, the continent’s first subway, the world’s first-ever telephone exchange, and Andrássy Avenue—a vast, leafy boulevard to rival the Champs-Élysées in Paris. Writers, artists, inventors, and philosophers gathered in the city’s cafés and baths to talk about the exciting, radical future.

Half a century later, the stucco had been blasted from Budapest’s once-elegant frontages, the glass from its windows, and its bridges had been blown up by the retreating Nazis. The world was divided between the two post-war superpowers: the democratic United States and the communist USSR, who, under the threat of an apocalyptic nuclear war, were locked in ideological combat—the Cold War. Each side sought to prove that its was the right way to build a bright new world by demonstrating technological and economic superiority and happier, healthier citizens.

In Europe, the divide was physical as well as ideological. The continent was cut in half by a vast, impregnable military barrier, passing along Hungary’s western border. No one could cross the Iron Curtain in either direction without permission from the highest levels of government, and activity behind it was invisible to the other side. The Soviets had installed a communist government in Hungary, and in place of the coffeehouse intellectual there was a new hero: the proletariat worker.

The vision for the country—shared by many of its homegrown communists—was of a centrally managed, classless state whose resources were shared equally among everyone. By 1950, all its mines, factories, and banks had been nationalized and the large country estates divided among the peasants. “You couldn’t own your own store or business any more. But most people kept their home, if it was a reasonable size,” says Dora. “Large houses were divided into apartments to house more families. You still see the effect of that in Budapest: one flat will have the kitchen, and the next-door flat will have the big bathroom.”

It made the Varghas’ strange encounter with the ávós in 1954 all the more baffling. As the district veterinarian for the farms and villages surrounding Kisvárda, János was indisputably a member of the former middle class, the hated bourgeoisie. Why had two ávós driven nearly four hours in the middle of the night to help a child they had never met? Years later, the family found out. “It turned out my grandfather was the vet for the parents of one of the pharmacists he had asked about the gamma globulin,” explains Dora. “And the pharmacist had a brother-in-law who was an ávó in Budapest at the time. The communist ideal was that everything should be shared equally, but in reality, access to scarce resources depended on who you knew.”

PRAMS

After the War, countries everywhere were short of the labor they needed to build a prosperous modern society—whether their economies were capitalist or communist. Hungary was in a dilemma: Without rapid industrialization there wouldn’t be a proletariat on which to build the communist state. But those of its citizens who had survived the War and were fit enough to work—even if they couldn’t be proven to be bourgeois or dissident—had fought (albeit reluctantly) on the side of Nazi Germany and were by definition ideological enemies.

While the U.K. encouraged mass immigration from its former colonies to swell its workforce, the Hungarian state directed its utopian gaze toward its children. Given the right education, enough food, and free health care, untainted Hungarian children would grow up to be productive, ideologically pure miners and steel workers. “Wherever you looked, you would see images of the healthy, muscular body of the hard-working citizen. You couldn’t get away from it. Statues, posters, newspapers, and magazines all depicted the same ideal,” says Dora.

To make that shining vision a reality, the government introduced a range of measures to encourage women to have children. It didn’t matter if they weren’t married. Propaganda reassured them: “To give birth is a duty for wives, and glory for maidens.” A special tax was levied against anyone over 20 who was still childless. From 1952, abortion was made a crime, accompanied by public show trials (guilt a foregone conclusion) of women charged with having abortions and the doctors charged with performing them.

To allow mothers to parade their babies proudly through Hungary’s streets and squares, the national bus-manufacturing company Ikarus started producing prams in 1954—the year György caught polio. One of Dora’s favorite images among the photographs and film footage she unearthed in her research—and one that is redolent of the era in which it was taken—is of a collection of pristine, bus-shaped Ikarus prams (with women cooing into them) in front of a row of proud, parental buses.

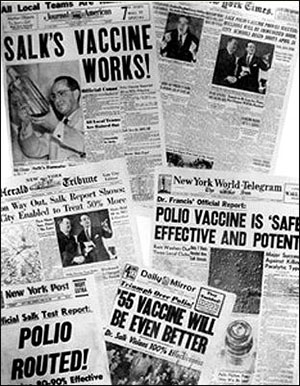

Enter polio. A disease that specifically targeted and disabled children, the first epidemic struck in 1952, the second—the one that paralyzed György—in 1954. That same year, Hungary watched closely as trials of the world’s first vaccine against polio began on more than a million children throughout the U.S. The trials were deemed a success and the injectable Salk vaccine, named after Jonas Salk—a Jewish scientist from New York, who developed it using an inactivated virus—was quickly introduced nationwide in the U.S.

In April 1955, the U.S. Cutter Laboratories (one of the companies licensed to produce the vaccine) released a batch containing poliovirus that had not been fully inactivated. As a result, almost 200 vaccinated Americans went down with paralytic polio. A Hungarian newspaper was swift to declare that “due to such negligence many thousands of children became the guinea pigs of the savage protectors of free enterprise.” The American Medical Association, meanwhile, blamed the “Red Menace” of socialized medicine in the form of mass trials for the notorious “Cutter incident.”

Yet in June the following year, after a series of international success stories had confirmed the safety and efficacy of the Salk vaccine, Hungary decided to start producing it domestically. It went even further and sent two virologists and the director of the Human Vaccine Production and Research Institute (a nationalized vaccine production company) to Denmark, a center of polio research in Europe at the time. That they were allowed to travel across the Iron Curtain was remarkable, all the more so considering that scientists, like vets and doctors, had been kingpins of the conservative pre-war society. America was less liberal with its own scientists, rejecting 600 passport applications on political grounds before 1958.

However, doctors and scientists were in short supply. Many had fled when the Nazis occupied Hungary in 1944. Others had returned from Russian prisoner-of-war camps “unable to work” (as a result of deprivation or torture) or been deported to the Siberian gulags because of their “bourgeois” affiliations. The desperate need gave scientists more freedom than academics in the more politicized humanities and social sciences, says Dora. “The Party turned more of a blind eye to their political and ideological views, and after a while many physicians and scientists actually regained the social status they had before the war. There wasn’t a clean break from the pre-war society—just a new set of inequalities.”

Four months after its scathing condemnation of America, the Hungarian government was forced to make a rare admission of negligence itself. The construction of new hospitals was one of the objectives set out in the first Five-Year Plan, of 1950, an economic blueprint for rapid industrialization. But on October 19, 1956, Health Minister József Román told the leaders of the health institutes that none had been built. Existing hospitals were overcrowded, and to cope with the strain other buildings—not originally intended for health care—had been converted into makeshift infirmaries (the ORFI was first established in a former hotel). Román also admitted that public health and epidemiology had been neglected.

The lack of investment in health care was a stunning omission, particularly since free health care was a key tenet that communist leaders used to distinguish their system from the capitalism of the West—supported by the belief that a healthy body led to a healthy mind that would choose the most rational ideology (theirs). The government also took the rare step of allowing public discussion of those concerns in the media. “For a brief moment in time newspaper reports spoke the same language as those in the ministerial archives,” says Dora.

Her grandparents saw the reality. György’s hospital in Debrecen was unable to cope with the ever-increasing influx of children with polio. János’ medical contacts had advised him that the ORFI had a large polio ward and offered the most advanced treatment and surgeries for polio-induced paralysis, so the Varghas transferred their son 250km away to Budapest.

Only three at the time, György now has just fragments of memory of the period he spent in Debrecen, enduring agonizing daily lumbar punctures (spinal taps, in which a needle is inserted into the lower part of the spine; even in the early 1950s it was seen as an outdated, and painful, treatment for polio). “I remember lying on my belly on an operating table, crying in pain,” he says. “And lying on my back in my bed, which was in the far corner of a ward with perhaps 12 other children. When the nurse came towards my bed I started crying before she even reached me.”

TANKS

On October 23, 1956, tens of thousands of students, workers, writers, and intelligentsia marched together to Parliament calling for greater independence for Hungary from the Eastern Bloc and “the rights of free men for all its citizens.” The government labelled the revolt “chauvinistic, nationalistic, and anti-Semitic,” and Moscow sent in its Red Army to help quell the “counter-revolutionaries.” Street battles with tanks, machine guns, and Molotov cocktails ensued, making new craters in Budapest’s patched-up façades, as rebels set the ávós’ black Pobedas ablaze.

Five-year old György witnessed the uproar from the ORFI. Sat upright on a raised physiotherapy bed he could see out of the window to the navy-blue waters of the Danube in the distance. He had a clear view when a tank directly outside raised its gun at a machine-gunner on the roof of the neighboring building—to the electrified György it looked as if it was pointing directly at the hospital. Eventually, his parents came to take him home to Kisvárda; the ORFI couldn’t look after him any more as food and medical supplies had run dry due to the revolution.

With all international communications down and airports closed, Budapesters relied on Radio Free Europe (RFE), a CIA-funded broadcasting network, to let relatives abroad know they were all right as the violence raged on. RFE broadcasts from the West offered tactical advice to the “freedom fighters” and urged them to hold on, assuring them that help was on its way.

In the last days of October 1956 RFE served another purpose. Another polio epidemic erupted in the midst of the revolution, but the iron lung at the hospital in Debrecen, where György had first stayed, was broken. A replacement was needed urgently to save a child’s life. The hospital contacted local radio stations, which broadcast an appeal. It was picked up by RFE and made its way to Munich, where the West German Red Cross managed to track down an iron lung.

In the evening of October 29, a German plane carrying the lung crossed the Iron Curtain and made its way toward Debrecen airport. But the fighting had spread to Debrecen, the airport was in darkness and with all the phone lines down it was impossible to reach anyone who worked there. The nearest alternative was Miskolc airport, over 100km away. The radio station in Miskolc broadcast an urgent appeal—and its citizens responded. People living near the airport illuminated the area with lights, while local amateur radio transmitters contacted the plane and helped guide it safely to the ground.

On November 1, in Budapest, revolutionary leader Imre Nagy announced that Hungary was withdrawing from the Warsaw Pact (the Eastern Bloc equivalent of NATO) and appealed through the U.N. for the U.S., the U.K., and other powerful countries in the West to recognize Hungary as a neutral state, no longer aligned with the USSR. He also set out plans to transform the country into a multi-party democracy.

Across the river on Rózsadomb (Rose Hill), one of the leafy hills overlooking all the turmoil from the Buda side, five buildings had been seized by the rebels. Once the luxury villas of the pre-war bourgeois elite, they had been nationalized by the communists, then turned into a kindergarten for the children of the Party elite. On November 4—three days after his bid for Hungary’s independence—Nagy paused in the midst of trying to implement those radical changes and gave orders for orthopedist Dr László Lukács to set up a specialized polio hospital in the annexed buildings.

This was to be the only one of his orders that was fulfilled. A few hours later, a Soviet radio station announced the formation of a new Hungarian government headed by a new Moscow-installed leader, János Kádár, who declared his dedication to eliminating imperialist, Western, “counter-revolutionary” elements from Hungary. Nagy was deposed and given sanctuary in the Yugoslav embassy (he was later arrested when he left the embassy and was tried and executed in secret).

No military support for the rebels arrived and by then, despite the promises broadcast by RFE, it was clear that it wasn’t going to. That same day, the USSR stepped up its intervention and the Russian commander-in-chief gave the order to attack.

György, back home in Kisvárda near the Soviet border, awoke to find the ground was trembling and rumbling. His father carried him to the edge of the road, where crowds silently assembled, watching the Soviet army march from the USSR toward Budapest. Hour after hour, the seemingly endless procession of tanks, big guns, cars, and soldiers filed past—terrifying to most onlookers but enthralling to a little boy.

LAUNDRY

The Soviet military finished routing the rebels by November 11. A day later, despite the hostility of a political elite who wanted their kindergarten back, Lukács upheld Nagy’s orders and opened the Heine Medin Post Treatment Hospital in the appropriated villas on Rózsadomb.

The communist elite had chosen well: It was a perfect place for children. The new hospital was surrounded by small parks and woods, and from the top of the hill the children could look down over the treetops toward the gleaming curve of the Danube and the fairytale domes and spires of the Parliament building far below. As well as being the only hospital in the country dedicated to the long-term effects of polio, the Heine Medin also became a home for children with polio whose parents couldn’t afford to care for them. “They could live together and grow up there together,” says Dora.

Party members who had lost their lovely kindergarten may have been compensated in one respect: The secluded location meant that polio-stricken bodies—the antithesis of the ideal, healthy proletarian body—were largely out of sight.

The next challenge for the Heine Medin was to equip itself—no mean task, considering the revolution had brought the country to a halt, the infrastructure was still down and supplies were scarce. Help came from the West, with the International Committee of the Red Cross coordinating donations of hospital beds, bed linen, surgical equipment, and medicine from all over Europe (the high-quality blankets from Sweden were known as the “Swedish blankets” for years afterwards). Meanwhile, the new hospital’s only van had been hit in the street fights and sported a large hole in its side and base. Children and babies paralyzed by polio were carried up the hill to the Heine Medin with the clean laundry, in laundry baskets tied to the inside of the van.

It was perhaps inevitable that children paralyzed by polio sometimes had to undergo painful rehabilitative surgery that failed or was even injurious. For one of the patients Dora interviewed, polio made her legs uneven in length. To help her walk more easily, Lukács sawed off a part of her unaffected leg near the knee joint—one of the most common surgeries at the hospital—so that instead of one bad and one good leg, she ended up with two short legs. Because ether in large doses was considered dangerous for children, some weren’t given full anesthesia for the operation. “I still remember the pain and the sound of him tinkering away at my bones,” she told Dora. “Even though they said I wouldn’t feel anything, I can tell you I felt every single thing.”

Down the hill in the ORFI, György’s first operation—an attempt to manipulate his muscles, when he was four—had also turned out to be painful and superfluous. He was at least given ether, but found it extremely unpleasant. “Everything went dark after they put the mask on, then a red-orange color passed in front of my eyes. Then I fell asleep and when I woke up I vomited.” He also recalls the discomfort of being in a cast that enclosed his leg and his lower body for about six weeks after each operation. “I mostly lay in bed looking at the ceiling. It was very boring.” When it was hot the children sometimes begged the nurses to remove their casts at night to give them some relief from the unbearable itching. Sometimes the nurses did—risking the wrath of the head of the hospital, who occasionally made surprise visits to the wards in the middle of the night.

Once the cast came off for good, the real pain began: physiotherapy to re-tone the muscles that had been in plaster. It was a critical part of the rehabilitation process and could be more efficient than surgery, but György remembers the agony of having the therapist stretch and move his legs again.

The pain of physiotherapy, and the degree of cooperation required from the child, meant many of the children had an unusual amount of autonomy over what surgeries they had. Doctors and therapists took pains to forge strong relationships with them and gain their trust, so that they would buy into their treatment. When György was eight years old, the chief doctor and medical students came to his bed on their ward rounds and told him he needed another operation. He began to scream and shout at them. Sharing a hospital room with adult men had added some choice swear words to his vocabulary and he put them to good use now. “I sent the whole company to hell,” he recalls. The medics beat a hasty retreat, but the matter wasn’t over. György’s favorite physical therapist came talk to him. After she had managed to calm him down, she gently persuaded him to agree to give the surgeon a chance to explain why he should have the surgery before he made up his mind.

“Some of the patients call themselves dinosaurs because they’re the last of their kind. They’re the only repositories of knowledge of their disease, and it will die with them.”

Outside, the country was licking its post-revolution wounds. While help from the West had come for Hungary’s polio-stricken children, its revolutionaries realized that no help was coming their way. With the tacit agreement of the West, Hungary remained part of the Eastern Bloc. In the two years after the revolution, the new government led by Kádár meted out harsh punishment to the rebels: trainloads were deported to the Siberian gulags, while those remaining faced mass arrests, imprisonments and executions.

Once Soviet power was restored—and Kádár’s own position stabilized—things slowly changed for the better. Briefly, the revolution had unmasked the reality of the “People’s State” for the rest of the world to see. And the communist governments in both the USSR and Hungary had also learned an important lesson: If communism was to succeed in Hungary, there had to be bit more give in the system.

Gradually people’s lives became easier, albeit at a price. “The new government positioned itself as the paternalistic provider for and protector of its citizens,” says Dora. “But it wanted acknowledgement for that. In return for free health care education and mass-dining canteens it expected happiness, loyalty and gratefulness from its people.”

Before it could adopt that new role, however, the state had to rebuild homes, workplaces, roads, and power lines that had been damaged in the revolution—and treat citizens who had been harmed in the street fighting or by the polio epidemic. The challenge was compounded by the fact that in the immediate aftermath of the revolution, even basic necessities like soap were difficult to get hold of—and many of the 200,000 rebels who had fled the country were much-needed doctors and other professionals.

In desperation the state turned for aid to those it had driven away. It announced that all packages arriving containing food, clothing, and medicine—many of which were sent by dissidents who had fled Hungary—would be duty-free. It also offered amnesty to those who hadn’t been affiliated with the revolt. Around 50,000 Hungarians were lured back home in the early summer of 1957 (some of whom were imprisoned or executed despite that promise), but most of them never returned. However, as it turned out, the most disastrous immediate consequence of the revolution was the interruption to the production of Salk vaccine.

BEER

It was the summer of 1957. A heatwave enveloped Budapest, the temperature rising to a scorching 45°C. While Budapesters sought relief along the banks of the Danube and in the city’s outdoor spas and pools, the government took pains to ensure that beer production (by the nationalized breweries in Budapest’s Kőbánya district) would be sufficient to quench its citizens’ thirst throughout the long, hot summer.

Then, on June 27, a warning appeared on the back pages of newspapers: Polio had appeared in the city. In the following weeks its darkening shadow spread across the country, claiming more victims than it had in any of its previous visitations. As anxious parents followed its progress in newspaper and radio reports, mass organized vacations in the mountains or by Lake Balaton were banned and—in the relentless, claustrophobic heat—children were forbidden to go to the baths and spas.

Today, over half a century later, a similar heatwave has just broken in Budapest. “It was over 38 degrees in the city yesterday,” says Dora. “As I was walking around I was thinking, ‘Oh my God, what could it have been like in 1957?’ It was only the year after the revolution so there wasn’t time to rebuild everything and lots of people didn’t have running water in their homes. And then if you can’t go to the public pools, it’s just deadly, the streets get so hot. I took my son to this fountain where the water’s coming from the ground and the kids were running around enjoying the water and that was a lifesaver.”

The new Kádár-led government was in a quandary. Inadequate health care and the lack of doctors (and the criticisms of those who had stayed behind) had been one of the grievances driving the revolution six months ago—and it simply couldn’t risk another uprising. It needed to flex its muscles against polio—and be seen to win. But Hungary hadn’t yet begun to produce the Salk vaccine.

Once again, it turned to its enemies in the West and ordered a shipment of Salk vaccine from Denmark. The shipment (originally produced in Canada) was delivered by a West German pilot who had volunteered for the job on his day off and was heralded as a hero in the Hungarian press. For once there was no suggestion that he might be an imperialist spy.

Shortly afterwards, the government had to reach through the Iron Curtain again because the shipment brought by the West German pilot wasn’t enough for the entire population. It purchased a batch from the American pharmaceutical company Parke-Davis—and accepted a donation from the World Health Organization (WHO) of 40,000 doses—despite the fact that Hungary, along with other Eastern Bloc countries, had withdrawn its membership in 1949.

Perhaps most remarkably, it accepted further donations of vaccine from the national Actio Catholica organization. In the 1950s, the relationship between the Hungarian state and the Catholic Church was extremely fraught. The head of the Hungarian Church, Cardinal József Mindszenty, who staunchly opposed communism, had been tried, tortured, and given a life sentence in a 1949 show trial. The revolutionaries had managed to free him, and he was now living in sanctuary in the U.S. embassy.

The temporary but necessary graciousness toward its enemies seemed to pay off. When the next year passed without an epidemic—held up as proof that the campaign had succeeded—the Hungarian government had cause to congratulate itself. Or so it thought.

ICE CREAM

György, now aged eight, had his second operation in 1959. The surgeon divided a flexor muscle of his right leg, and reattached it to allow him to straighten it. He remembers a group of doctors gathering round his bed when the cast came off. “They said, ‘Extend your leg.’ I tried but it didn’t work and they were disappointed. Then the chief medical officer had an idea—she told me to bend my leg instead. I tried to, and it straightened! I was thrilled. For a short time I had to think of bending to extend my leg, then my brain got used to it.”

Outside, the city was sweltering in another heatwave. A newspaper article from the period warns people that all buses going into the hills were completely packed, reassuring them that if they went to cool off in the open-air baths instead, there would be enough beer and ice cream for everyone.

Then, on July 21, the impossible happened: A health minister’s report on the back page of Népszava, the trade unions’ newspaper, mentioned a growing number of polio cases in Budapest. Ten days later, a newspaper article warned parents to avoid crowds and swimming pools. Polio was back—with a vengeance. As the epidemic unfolded it again reached every corner of the country, the dreaded paralytic form claiming 1,830 new victims—just slightly fewer than it had in 1957. But this time everyone had supposedly been vaccinated. How could this have happened?

The mystery and fear were compounded by silence from the government. This time there were no weekly reports from the Health Ministry detailing the number of cases and what cities and counties were affected, as there had been in 1957. In 1959 there were only two reports throughout the long, hot weeks of the epidemic, and these discussed the success of the vaccination program before going on to blame parents for not taking their children to be vaccinated when they had the chance.

The internal papers of the Health Ministry, however, told a different story. There was hardly any mention of parental negligence. Instead the reports dwelt on practical, organizational issues that could have compromised the vaccination program. One was the lack of a clear registration system. Another was the difficulty in diagnosing polio when 95 percent of cases were abortive (non-paralytic). When polio was diagnosed, doctors and hospitals often failed to report it. And even if they did, information about when and how many doses of vaccine the child received (if any) wasn’t covered by the form.

There were also complaints from doctors that the needles supplied by the Health Ministry were leaking; many started using their own needles (working against the communist ideal of a centrally organized, standardized method). Moreover, doctors were suspicious of the injection method the government had chosen to adopt. Most countries injected 0.5ml of vaccine into the muscle, but the Danish method of injecting a lower dose (0.3ml) into the skin instead seemed to be equally effective. The saving was very appealing to the cash-strapped Hungarian government—which parents now blamed for lowering the dose.

Why had the Salk vaccine seemed to work in 1958 but not 1959? One suggestion is that another intestinal virus, the Coxsackie B virus, had been circulating in 1958 and may have interfered with the poliovirus in the gut, where it replicates, preventing an epidemic. Chris Maher, senior adviser on polio operations and research at the WHO, offers another: “The injectable, inactivated [Salk] vaccine gives really good individual protection, by boosting immunity in the bloodstream, but it doesn’t stop the live poliovirus from infecting the gut.” The virus replicates in the gut for a few weeks, without doing that particular host any harm, and is eventually shed back into the sewage system where it can circulate until it finds someone else to infect.

This, he says, is why samples taken from Israel’s sewage system in June 2013 were found to contain live poliovirus. “Israel has a highly immunized population, their basic coverage is 90 percent, but they use the inactivated vaccine. So when poliovirus of Pakistan tribal origin was brought over, no one got hurt. But people are obviously getting infected and shedding the virus—because we’re continuing to find virus. So there is the risk that they could end up with clinical cases of polio.” More worryingly, people from Israel, although protected themselves, could carry the virus to places where vaccination rates are lower, like southern or eastern Europe, and unknowingly infect many more people.

SUGAR

Back in 1959, salvation for the harassed Hungarian government and frightened parents arrived—and this time it came from the “right” side of the Iron Curtain: the USSR. Albert Sabin, a Polish-American Jewish researcher, had developed a new vaccine in the U.S. But he couldn’t test it there because a large proportion of children there had already been immunized with the Salk vaccine. So he had turned to the East and, in a much-lauded Cold War scientific collaboration, trials had begun in 1957 on millions of children in the USSR and Czechoslovakia.

This vaccine used a weakened (attenuated) rather than a killed poliovirus, and could be delivered orally on a sugar lump—a method that, in contrast to the Salk vaccine, didn’t require any medical expertise or specialized training. Importantly, the vaccine went straight to the gut where the virus replicates, so it would induce the immune system to stop the virus there so it wouldn’t be shed to circulate in the population; the harmless, attenuated virus would be shed in its place, immunizing anyone it infected who hadn’t been vaccinated. Although the new vaccine provided less personal protection than the Salk vaccine (it didn’t boost the immune system in the bloodstream so well), it seemed to be a better tool for protecting large communities.

The Sabin vaccine did not come without risks. The weakened but live virus might mutate in the gut and become more virulent, leading to vaccine-derived strains of polio. “If you’ve got high vaccine coverage in a population, vaccine-derived strains aren’t an issue—they need a large, susceptible population,” says Maher. This, he says, gives the virus time to mutate and develop circulating characteristics, by hopping from one susceptible gut to the next. And once the mutated virus does begin to circulate as a vaccine-derived strain, it has the same characteristics as wild-type (naturally occurring) poliovirus, including the power to cause paralysis. “The most active vaccine-derived strain circulating [in December 2013] is in Pakistan, in the same region as the wild-type virus, where there’s a very susceptible, unvaccinated tribal population,” he says.

Fifty years ago, this concern was exacerbated by Cold War suspicion. Doctors and scientists on both sides of the Iron Curtain distrusted the Sabin vaccine for the same reason: because it hadn’t been tested in the U.S. Americans doubted the reliability of Russia’s results (some even believed they may have been deliberately misrepresented, as part of wider attack on the West’s children). And some Russians were suspicious of a vaccine that the Americans had developed but not tested on their own children. Despite these concerns, Hungary took the plunge. It began its own trials of the Sabin vaccine on November 3-4, 1959, and a month later became the first country in the world to begin a nationwide vaccination campaign with it. By 1969, polio had been practically eradicated in Hungary, 10 years before the U.S. achieved the same result.

“The oral vaccine—the attenuated live vaccine—can knock it out of circulation completely because it creates immunity in the gut and stops the virus spreading. That’s why the first countries to use it could eradicate polio early on,” says Maher. “Once polio had been knocked out of some fairly large areas for good, that prompted health organizations to start thinking about global eradication. The oral vaccine has since been demonstrated to eradicate polio in just about every setting.”

In fact, he says the best possible vaccine schedule is a combination of the two. “In Syria [in 2013] the routine vaccination is a combination of the injectable inactivated vaccine and the oral attenuated one. A marriage of the two protects the individual and the community—it gives you a better bang for your buck.” However, the eradication campaign responding to an outbreak of polio caused by the civil war there (which has led to a drop in vaccination rates) is using the oral vaccine alone. “You use the oral vaccine to respond to an outbreak, because it’s easy to administer, it stops people shedding the virus back into the environment, and it helps protect the wider community.”

Yet even given the well-documented success of the Sabin vaccine, polio remains endemic in small pockets of Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Nigeria, where vaccinators are prevented from gaining access to unvaccinated children.

“Worldwide, people aren’t refusing the vaccine at a household or community level because they think it might harm them. That’s not a significant issue now,” says Maher. “The main obstacle is armed conflict; the group in control will decide not to allow us in.” Often, he says, it’s not that they don’t trust the vaccine or that they think it’s a Western plot to poison their children. They’re more wary of the idea that vaccinators, as they move from house to house, might be as gathering intelligence, passing information around, or marking houses. “In an era of target-marking and air attacks, it’s not an entirely illogical position for these guys to have,” says Maher, “but it certainly makes life complicated for us.”

SNOW

Winter came. Snow settled on the Heine Medin’s elegant buildings up on the hill. Down below, in the ORFI, there was no lift, and as nurses couldn’t carry the bigger children up and down the stairs, those living in the upstairs wards could no longer leave them. The nurses brought snow in from outside to show them.

György underwent two further operations on his left leg there, and by 1961, aged 10, he could finally stand again. Once he could walk, his parents paid for him to learn to swim in the outdoor pool of Lukács Thermal Baths opposite, where, overlooked by slim, mullioned windows in the ochre façades, he played ball with his friends from the hospital in the shallow end, or watched the vigorous games of water polo being played at the other end.

By 1963, polio was becoming a distant memory in Hungary thanks to the Sabin vaccine. As a result, the victorious state turned its attention to more pressing matters. It stopped trying to get hold of iron lungs, respirators, and other medical equipment from international organizations. And because of the lack of new patients, after just six years as a dedicated polio hospital designed to support patients for life, the Heine Medin hospital on Rózsadomb was transformed into a general hospital.

“Once you’ve got protection covered—and no one’s going to get ill again—treatment becomes a non-issue and so lots of questions can be left unexplored,” says Dora. “But in Hungary there were still thousands of existing patients, and now there was no organized, dedicated care for them. Everybody was dispersed and had to fend for themselves without any trained physicians or physical therapists or nurses, or access to specialist equipment.”

The problem persists today. Many childhood survivors from the Heine Medin and ORFI hospitals, who Dora interviewed for her research, are now dealing with post-polio syndrome: increased weakness and pain in the muscles, starting 20-30 years after the original infection, probably caused by the decades of extra stress placed on the remaining nerve cells. Or they continue to need specialist medical equipment such as respirators or movement aids, which have to be prescribed by doctors with little or no knowledge of polio. “They’re only taught the virology part of it in medical school and nobody’s doing the treatment any more, so it’s very difficult to find doctors who actually know how to help them,” says Dora. “Some of the patients call themselves dinosaurs because they’re the last of their kind. They’re the only repositories of knowledge of their disease, and it will die with them.”

If their families didn’t have the resources to care for them, or they were orphans or wards of the state, the children no longer had a permanent home to grow up in. They were moved around the country, from place to place, housed temporarily in palace ruins and other abandoned buildings from a former era—sometimes even in mental asylums. The important thing was to keep them invisible: their disabled bodies spoke too eloquently of the state’s earlier failure to protect them.

György was one of the lucky ones. He moved back home, and went regularly for physio to the hospital in Debrecen where he was first treated as a two-year-old. It is now linked to the university at which he is now professor of microbiology. He still loves swimming. He recalls how, once he had learned to swim all those years ago in Lukács Baths, he loved to dive in, through the steam rising from the water into the chilly November air, hiding the other swimmers from sight, and down to where he could finally stretch out his legs and kick.

This post originally appeared on Mosaic as “Hungary’s Cold War With Polio” and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.