While male mosquitoes flit around harmlessly after growing out of waterborne larval phases in search of buggy love, occasionally slurping at pollen or fruit juice, it’s the females that suckle our skin. When a proboscis is plunged into our flesh, malaria and other diseases can be unwittingly exchanged by the female for blood-borne proteins she needs to manufacture eggs.

More importantly, at least from an ecologist’s perspective, it’s the egg-laying limitations of a mosquito population’s females that limit population size.

Fortunately, an international team of researchers has found a way to do something better than send female mosquitoes to graveyards. They demonstrated a method for genetically engineering them to near non-existence.

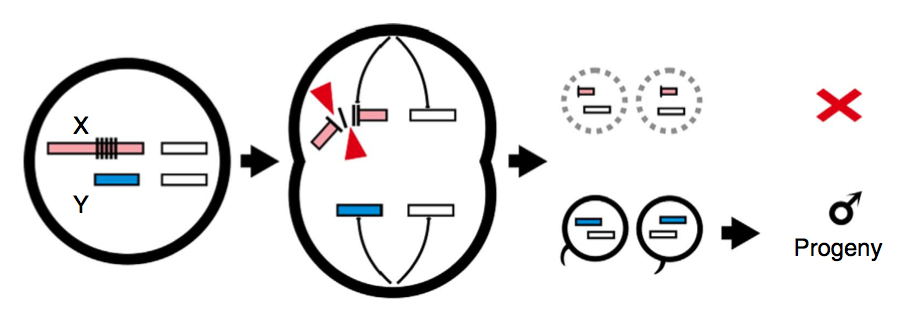

The scientists set out to re-engineer a mosquito enzyme, known as I-PpoI, which is involved in cleaving x chromosome gene sequences. (As a general refresher, xx = female and xy = male; gender of offspring is determined by whether the egg-fertilizing sperm bore an x or y chromosome.) The genetic manipulation was aimed at shredding paternal x chromosomes during sperm formation, leading to generations of increasingly male-heavy populations. Here’s a model from the new Nature Communications paper, explaining that aim:

(Chart: Nature Communications)

The researchers developed a number of I-PpoI variants, the most effective of which produced generations of at least 95 percent male offspring when bred with wild-type females—without affecting the overall fertility rate.

“We aren’t simply killing off the female offspring of our modified males,” says Nikolai Windbichler, a research fellow at the Imperial College London. “If we did that, we would reduce their reproductive output by 50 percent. Rather, we prevent females from being produced in the first place. So, rather than eliminating 50 percent of the progeny of males, i.e., all the females, they are replaced by males, which makes this a much more powerful tool.”

Because the engineered trait is hereditary, the benefits of the genetic manipulation should grow over time, though the researchers warn that population resistance would be a threat.

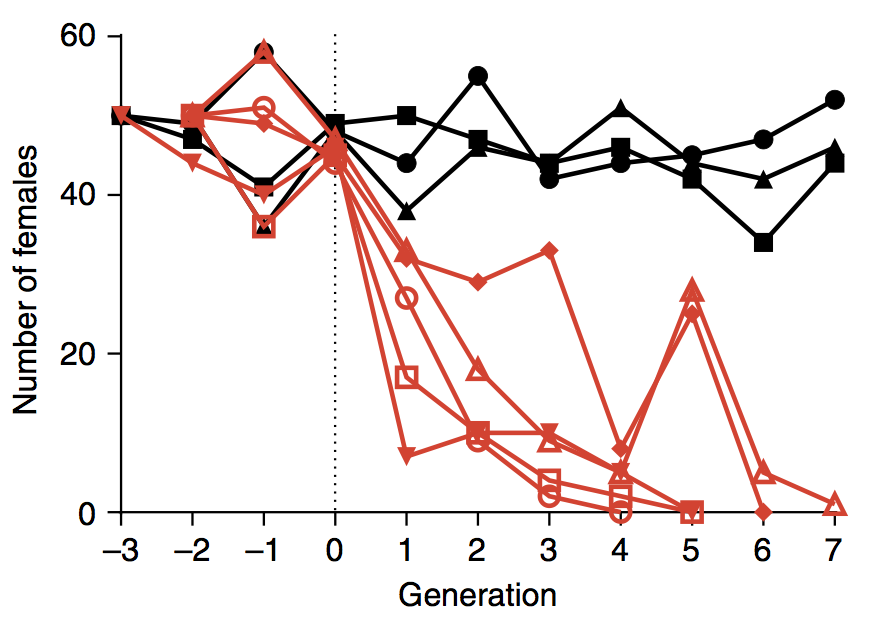

Here’s a chart from the paper showing the results of lab experiments using populations that began with 50 wild-type males and 50 females. Shown in red is what happened when three engineered males were introduced at generation zero for every wild-type male. The black lines show the result of control population experiments.

(Chart: Nature Communications)

Only one mosquito genus, Anopheles, a name derived from a Greek word meaning “good for nothing,” spreads malaria. This research focused on A. gambiae and A. arabiensis, the primary malaria vectors in Sub-Sahara Africa. The results offer hope for developing a new weapon against the disease, which is estimated to afflict 200 million people every year, killing 500,000 of them annually.

“This is very promising, but we have many steps to go,” Windbichler says. “We will test these strains in ever-larger enclosures that are more and more field-like. We will also have to address all aspects of biosafety and ethical as well as regulatory considerations.”