For several years, a number of scholars (including me) have been making the case that American political parties are best thought of as loose networks of interest groups, candidates, donors, activists, and others, rather than hierarchies organized under the DNC or RNC. (You can see examples of such studies here, here, here, here, and here.) The way we think of parties is vitally important to how we treat them. If we want to regulate parties or restrict their activities or even ban them, that’s far easier to do if they’re rigid hierarchies than if they’re flexible networks. The latter can adapt to a great many impediments.

A set of donors is serving as a gatekeeper to office. If you meet their approval and gain their financial support, you have a good shot of attaining office. If you don’t, you’re probably wasting your money.

In a new paper, Bruce Desmarais, Ray La Raja, and Mike Kowal have shown that not only do these networks exist, but that they exert a powerful influence over elections, making it far easier for candidates tied to the networks to win. These political scientists focus on partisan funding networks, using social network analysis (SNA) tools to detect consistent communities of donors. Examining the thousands of transactions between donors, interest groups, and congressional candidates each cycle, they discover that incumbents receive their support from a set of well-endowed funding constituencies. Non-incumbent challengers, meanwhile, get their support from all sorts of donors. However, those challengers who receive support from the same communities backing incumbents tend to win more often.

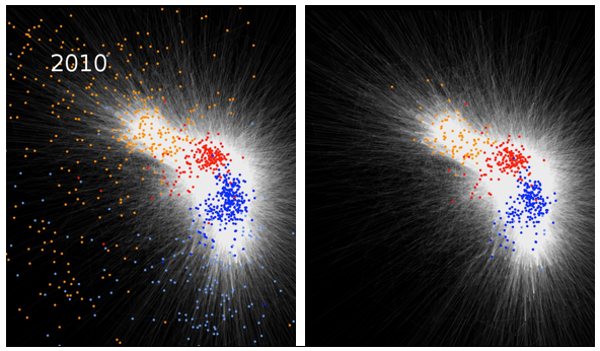

Below is a network visualization they used in their study. It shows the links (thin white lines) between political action committees (not shown here) and the candidates (red for Republican incumbents, orange for Republican challengers, blue for Democratic incumbents, light blue for Democratic challengers). The graph on the left is all the congressional candidates in 2010. The right depicts only those who won their races:

The important takeaway here is that those challengers who won their races appear much more central to the funding network than those who lost. As the authors write:

The winning challengers in the right graph received money from similar “communities” of interest groups (in contrast to orange and light blue challengers in the left graph who appear scattered outside the core)…. This pattern suggests strongly that ideologically coherent sets of donors behave very much like traditional parties by backing a selective group of challengers and helping them win.

The authors go on to demonstrate that the advantage provided by these networks is more than just total dollars. Even at similar levels of spending, challengers with these communities’ support do about twice as well in elections as those without it.

For example, imagine a wealthy businessman or athlete decides to run for Congress as a Republican, but local Republican insiders are wary of him because they’re unsure of his stances on some key issues, so they decline to donate to his campaign. No worries, right? He’s got plenty of cash, so he plunks down $2 million to put himself in office. More likely than not, he’ll fail, whereas a candidate who spends $2 million raised through these insider donor communities will have a much better chance of getting in. It’s not just how much money you spend; it’s whose money you spend. (The authors provide additional evidence in the paper for their causal story, demonstrating that it’s the funding that helps the candidates, rather than the donors just rallying behind the candidates who appear to be doing well.)

Another way of saying this is that a pretty well-established set of donors is serving as a gatekeeper to office. If you meet their approval and gain their financial support, you have a good shot of attaining office. If you don’t, you’re probably wasting your money. This is the essence of a party. They get to decide who gets in and who doesn’t, and they’ve been doing this in one form or another for hundreds of years. The smoke-filled room has a lot less smoke in it than it used to, but it’s still there, and if you want to hold office, you want to win the favor of the people inside of it.