The honeybee waggle is no tear-jerking form of interpretive dance. The idiosyncrasies of the figure eights that bees do after returning to the hive from a successful foraging run are purely practical. They tell other bees the direction they need to fly to hit the blooming banquet of nourishing pollen and energy-packed nectar from which they just returned—and how far they must travel.

“Satellite surveys and other remote surveys will not tell you anything about pollinator preference for different land types. Here, we let the bees tell us with their unique language where they prefer to collect their food.”

The function of the waggle dance has been known for half a century. By interpreting the dance of bees in a colony, scientists have previously figured out how far the insects were traveling. Which can be a long way. A paper published in 2000, for example, reported that 10 percent of bees studied in the British city of Sheffield were traveling six miles during a heather bloom.

Which is neat. But is there any way we can interpret the information that’s coded in waggle dances to help inform environmental policymakers?

In a paper published online Thursday in Current Biology, University of Sussex researchers describe how they interpreted colonies’ waggle dances to create a useful environmental map.

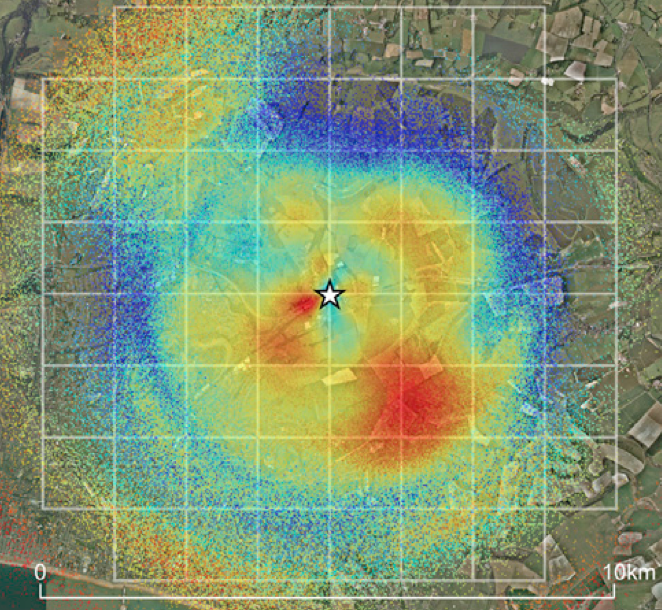

Here’s a map that the team created by studying 5,484 waggle dances during two years in three experimental hives at a laboratory surrounded by farms and neighborhoods. The map has been corrected for bees’ bias to forage closer to home when good food is available there, rather than farther from it. The star shows the site of the experimental beehives. Red colors reveal a high probability of visitation. Blues reveal a low probability, and no color basically means that the area was of no interest to the bees.

Maps like this aren’t just cool to look at—the scientists also overlaid the map with information about land use, yielding findings about the types of land management approaches that could best support insects that pollinate crops and wild plants. Pollinator protection is growing in importance worldwide as hives collapse and butterfly and bumblebee species march toward extinctions.

Lands that were highly managed to produce environmental benefits under a European Union scheme were visited more often by the bees than the researchers had expected—perhaps because the conservation approach involves protecting grasslands, which yield wildflowers. Land managed under a different, organic approach, which calls for the sowing of nectar-rich plants, however, was visited less often than anticipated—perhaps because the approach includes mowing to keep weed species at bay.

Margaret Couvillon, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Sussex involved with the research, says the new bee-assisted mapping technique could also be used in the United States.

“While our study gave specifics about bee foraging preference, the study is also a proof-of-concept,” she says. “Satellite surveys and other remote surveys will not tell you anything about pollinator preference for different land types. Here, we let the bees tell us with their unique language where they prefer to collect their food. Because they only dance for good sites, we can see what areas are providing the best forage.”