There’s an inevitable obstacle that arises in the conceiving of fictional alien life: Our own inability to conceptualize life that is not, at least in some small way, a reflection of us. The “grays,” probably our most well-known fictional visitors, with their large heads and bulging eyes, are fairly obvious distortions of the standard human physique.

Unlike many of its galactic fellows, the Xenomorph doesn’t fly around in a spotless ship of unfathomable technology. Giger’s creature is a filthy, primal parasite whose very survival is contingent on it’s continued rape and exploitation of other species.

When Academy Award-winning Swiss artist H.R. Giger passed away on Monday, he left behind, among his endless menagerie of horrors across a wide array of media, including painting, film, sculpture, and music, one of the most unique depictions of alien life ever put to screen. The titular alien, heretofore referred to as the Xenomorph, from Ridley Scott’s 1979 science fiction horror classic, wasn’t inspired by the stars. Instead it came from deep within mankind (sorry John Hurt) and somehow developed into something more alien and terrifying than anything from the unknown.

More optimistic conceptions of alien life involve two key traits. The first is a high level of technology which has not only allowed their race to travel great distances, but, more importantly, has freed them from the need for aggression. Prior to Alien, Close Encounters of the Third Kind became a critical and commercial hit behind the idea of a mysterious but ultimately friendly and benevolent alien visitors. They possessed a level of technology that not only allowed travel at great distances, but had seemingly allowed them to eliminate the need for violence against another species. The second key trait is expanded mental capacity or enlightenment through which the aliens have achieved interstellar cooperation with other races, such as in Star Trek’s universe of largely peaceful interspecies interaction, and/or psychic abilities. The idea of the enlightened alien is an inherently optimistic reflection of humanity. It is our best qualities extrapolated into the far future. Our best hope for ourselves.

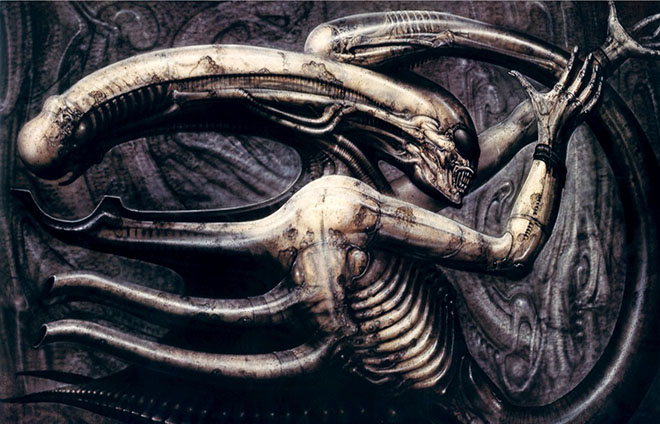

Necronom IV. (Photo: H.R. Giger)

Famed science-fiction screenwriter Dan O’Bannon (Total Recall, Dark Star) and Ronald Shusett, who wrote the original draft of Alien, wanted to make a movie about interspecies rape. The script called for a creature that, after impregnating one crew member on the space freighter, The Nostromo, would go on to force itself on the rest of the crew. For that, they needed a creature that reflected not the best that life in the known universe had to offer, but the worst. O’Bannon had worked with H.R. Giger on Chilean director Alejandro Jodorowsky’s failed adaptation of Dune and remembered his terrifying designs. He gave Alien director Ridley Scott a copy of Giger’s Necronomicon. In it, they found the perfect basis for their movie monster, Giger’s Necronom IV.

Unlike many of its galactic fellows, the Xenomorph doesn’t fly around in a spotless ship of unfathomable technology. Giger’s creature is a filthy, primal parasite whose very survival is contingent on it’s continued rape and exploitation of other species. If this sounds like a familiar concept, it’s because, at least according to Giger, it was an accurate, if a little pessimistic, reflection of humanity’s most basic function. Throughout his career, Giger made a point of highlighting the dark side of the human life cycle so often worshipped as a source of hope and positivity. While we celebrated births and treasured our existence, Giger produced pieces like Erotomechanics VII, which sapped thought and feeling from the act of reproduction and reduced them to what he saw as the truth: the cold, mechanical struggle to survive. To Giger, sex and birth could be pain and even kill. Every life, he posited in his piece Birth Machine, carries the potential for suffering. In Necronom IV, we see the phallus and the monster depicted as one, a fusion of a symbol of life with its inherent potential for pain and trauma. Giger’s message was very clear: That thing between your legs is also an instrument of evil.

The facehugger. (Photo: 20th Century Fox)

Giger’s philosophy was apparent in the Xenomorph’s physical being, but it made its way into the creature’s life cycle, too. It began with forced entry, with the facehugger pushing its embryo down a host’s throat. Its birth—a forced exit—would be even more violent, bursting forth from the host’s chest cavity, inextricably linking its life to the death of another creature. As an adult, it kills with another phallus, a set of pharyngeal jaws. This is what made the cold, unthinking Xenomorph so terrifying and made Alien as much a horror film as it was science fiction. It turned our own weapon against us, so to speak, and showed us the terror of what we do to each other and the creatures we torture and exploit every day as a matter of simple survival. It was a penis come to life, running amok in a ship full of dark corners.

None of this is meant to take away from what O’Bannon, Shusset, and Scott achieved with Alien—which made Scott a household name, earned back its budget 10 times over, and made a star out of Sigourney Weaver as much as the Xenomorph itself—but they were undeniably gifted a great treasure in Giger’s creation. While others looked to the stars for inspiration, the Xenomorph was dredged from the filthy and most basic truths of our existence, a look backwards at our primordial selves. Seeing that on screen was more terrifying than any green-skinned, antennae-sporting alien in a UFO.