The name of the renminbi (RMB), China’s national currency, translates to “the people’s currency,” and, true to its name, it was born as a tool of the people. First issued on December 1, 1948, by the Chinese Communist Party while the country was embroiled in a civil war between the Communists and the nationalist Guomindang (which translates to National Party, using the same “min,” or “people,” as renminbi), the new currency was created to bolster the Communists’ hold on their occupied territory. When the Nationalists were defeated the following year, it became apparent that the revolution had caused a wild case of hyperinflation that the CCP controlled by lopping four zeroes off of their money’s value: 10,000 renminbi were suddenly worth just one.

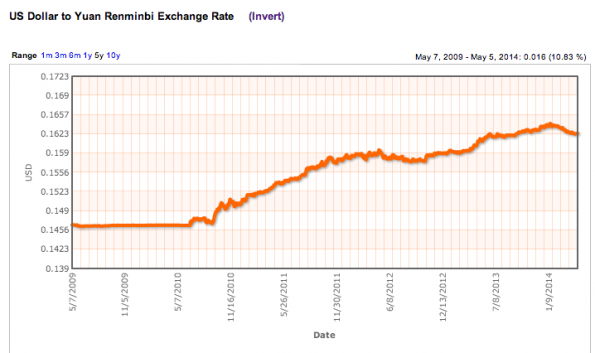

The renminbi’s tumultuous creation story highlights a certain truth about all currencies. Though we like to think our money is a stable entity that we can trust to hold its value, the reality is that it is just as ad-hoc and unstable as the nations that use it. These days, after trending upward in value ever since its creation, the renminbi is actually falling. The currency hit a low of 6.26 yuan (the Chinese word for coin, abbreviated ¥) to the dollar this month, down over 3.3 percent from the beginning of this year.

The fluctuation is surprising because, historically, the Chinese government has strictly controlled the renminbi’s value against the dollar. Since its early history, the currency was “pegged” to the dollar, meaning the exchange rate between the two stayed stable at a particular level set by the government rather than changing with the daily demands of the market. First, it was held at ¥2.46 to $1, then it appreciated to ¥1.50 to $1 in 1980—artificially giving the RMB a much higher value against the U.S. dollar than it has now.

Currencies are tools for political as well as economic nation building, as the case of China shows. Manipulating the RMB is one way the CCP can put its policies into action without the overt impact of announcing them publicly.

As China’s economy opened up in the late 1980s, the government intentionally shrank the value of the RMB against the dollar in order to encourage exports: With a cheap RMB, importing goods from China was also cheap. The all-time low came in 1994 with an exchange rate of ¥8.62 to $1.

A pegged currency meant that China was playing with a stacked deck when it came to the international market—the government was giving its national businesses a handicap to better compete against their Western counterparts, a major part of what caused (and continues to cause) the made-in-China boom. The Chinese government faced increasing pressure to allow its currency to fluctuate, which it eventually did when it un-pegged the RMB in 2005. The currency immediately gained in strength against the dollar.

But when the financial crisis hit in 2008, China again took measures to control the value of its currency, which continued until 2010 when the government announced it would resume monetary reforms. Rather than being pegged to the U.S. dollar, the RMB is on a “managed floating exchange rate” attached to a handful of international currencies, heavily weighted around the dollar, the Euro, the Japanese yen, and South Korean won—all currencies that exert a major influence on China. This means that the value of the RMB can move up and down to a limited extent, but not too much; in March of this year, that variation band was set at two percent.

Superficially, this looks like a continued liberalization of the currency and an acceptance of the international market. Recently, the market seems to have devalued the RMB on its own and the currency is listing toward the lower side of the two-percent range. But not all is what it seems with the country’s money.

THE RMB IS INDEED getting cheaper again, but perhaps not because the market deems it to be worth less. Rather, the Chinese government wants it to be. The New York Times reports that for the yearlong period ending March 31, the Chinese central bank spent $2 billion every day selling RMB and buying foreign currencies. “This prevented the renminbi from rising and, more recently, helped weaken it,” Keith Bradsher writes. This suggests that the government is again intentionally manipulating its currency’s price under the guise of continued reform.

Just as it did in earlier decades, a cheaper RMB makes it easier for China to export goods and create jobs at home, a salve to the impact of the world’s ongoing economic problems as well as rumblings of dissent from within the country. Tibet is still occupied and the Muslim-Chinese region of Xinjiang has been hit by a recent series of dramatic attacks ascribed by the government to religious extremists. The government just detained a handful of high-profile dissidents before the anniversary of Tiananmen Square.

For China’s lower- or middle-class citizens, the RMB’s fluctuations aren’t a day-to-day concern; the monetary policy impacts the wealthy and the entrepreneurs who are constantly moving money in and out of the country much more heavily—the same people who might be tempted to speak out visibly against the government. A gently depreciating RMB temporarily benefits that higher class while consolidating the national economy. Perhaps the Chinese government is pursuing a policy not unlike Putin’s in Russia: Reward the oligarchs, and they’ll fall in line.

Currencies are tools for political as well as economic nation building, as the case of China shows. Manipulating the RMB is one way the CCP can put its policies into action without the overt impact of announcing them publicly. RMB depreciation dampens currency speculation, putting off foreign investors who think the RMB’s rise is inexorable, as well as reminding Chinese investors that keeping their money at home can be a good thing.

China has conflicting motives: On one hand, to use its currency to its own advantage, and on the other, to play nice with international markets in a bet for future business and the efficiencies of integration. Every country faces the same conflict, yet too much manipulation could sacrifice one side for the other. Monetary policies require a balance.

“To secure its own long-term growth and contribute more to global growth, China needs to shift to a growth model that relies more on consumption and less on investment and exports,” one anonymous senior Obama Treasury official told the Financial Times. “A change in China’s policy away from allowing adjustment … would raise serious concerns.”

Of course, keeping China toeing that market line is also precisely what would be good for the U.S. economy.