Twenty-five years ago, Pam Houston used the money she’d earned from her beloved first short story collection, Cowboys Are My Weakness, to put 5 percent down on a 120-acre ranch in the Colorado high country. Since then, she’s made a life for herself there, sharing her mountain-surrounded home with a collection of Irish wolfhounds, horses, miniature donkeys, and Icelandic sheep. Over the years, Houston says, she’s found solace in the daily and seasonal rhythms of the ranch—while weathering droughts and fires and reckoning with the fate of the planet.

Yet the home Houston loves is also a home she’s constantly leaving. As she quips in her new book, Deep Creek: Finding Hope in the High Country, “[F]or a person who flies 100,000 miles most years, choosing a place five hours from the Denver airport was something I might have given a little more thought.” On the December day when we spoke by phone about her new book, Houston was driving to Denver to catch a flight to Uruguay, where a friend of hers hopes to turn a ghost town into a community for artists. Houston had never been to Uruguay before. Traveling, trying something new—to Houston, that’s the easy part. The hard part is staying: “Can I commit to something that is more important than me, this piece of land? Can I stay put enough to take care of it?” The ranch, she says, became the real adventure of her life.

In her new memoir, Houston has rendered that adventure as a kind of love letter to the ranch. She had a difficult childhood, and in this book she lays out, simply but searingly, the abuse and neglect she experienced. In her life at the ranch, Houston says she’s found the sense of healing and protection that she lacked growing up.

Deep Creek is about falling in love with a landscape, but it’s also about what it means to live in a world threatened by climate change. Houston spoke to Pacific Standard about the healing qualities of the ranch, how her relationship with the landscape has changed over the years, and how to love the Earth, even in its broken form.

At one point, the working title for this book was The Ranch: A Love Story. But you ended up with a title and a book that feel much broader. How did that shift come about?

I was really trying to stay put, narratively. I said to myself early: OK, you can’t rely on your old tricks. Now that’s a terrible thing to say to yourself as a writer; I hope to never say it again. But I did, which meant to me: No quick changes; [don’t] get bored, go somewhere! That’s my narrative strategy. It’s also my life strategy. You know, it’s interesting that I just got married too. It’s like I’m trying so hard to be a person who doesn’t have to change it up every five minutes.

[F]or the first couple years of writing, [I told myself]: I am not leaving this ranch. Then a couple things happened. I had to think about the why of the ranch and the why of this commitment. It was actually my agent who said, “Isn’t this the book where you really talk about what happened to you as a kid?” And I thought, dear God, have I done anything else? Then I realized I hadn’t exactly—I had talked around it and I had alluded to it. So I thought, well, yeah, I guess that’s the why of the ranch.

-The other thing that happened was everybody’s growing awareness and urgency about climate change. I thought, I’m writing this sweet book about my love affair with this piece of pristine ground (which of course is not pristine, but you know what I mean), and it’s the last acreage that’ll go underwater. What kind of asshole does that make me, to write this book about, “Oh, I have this beautiful spot up here, when everybody else is submerging?” So then I thought, well, that’s got to come into this book as well, or I’m conscienceless.

The healing quality of the ranch and of nature in general for you—it can be hard to put into words. How did you approach trying to write about that experience?

I feel like it’s my primary job as a writer to describe the natural world, and in this case the ranch, in precise physical detail. To me, that’s the whole key of writing, actually: to get the concrete physical world, whether it’s the ranch or the grass or the mountain or the Walmart—whatever it is, to render that with as much sensory detail as is absolutely possible, so the reader can feel it. And feel it with all of their senses.

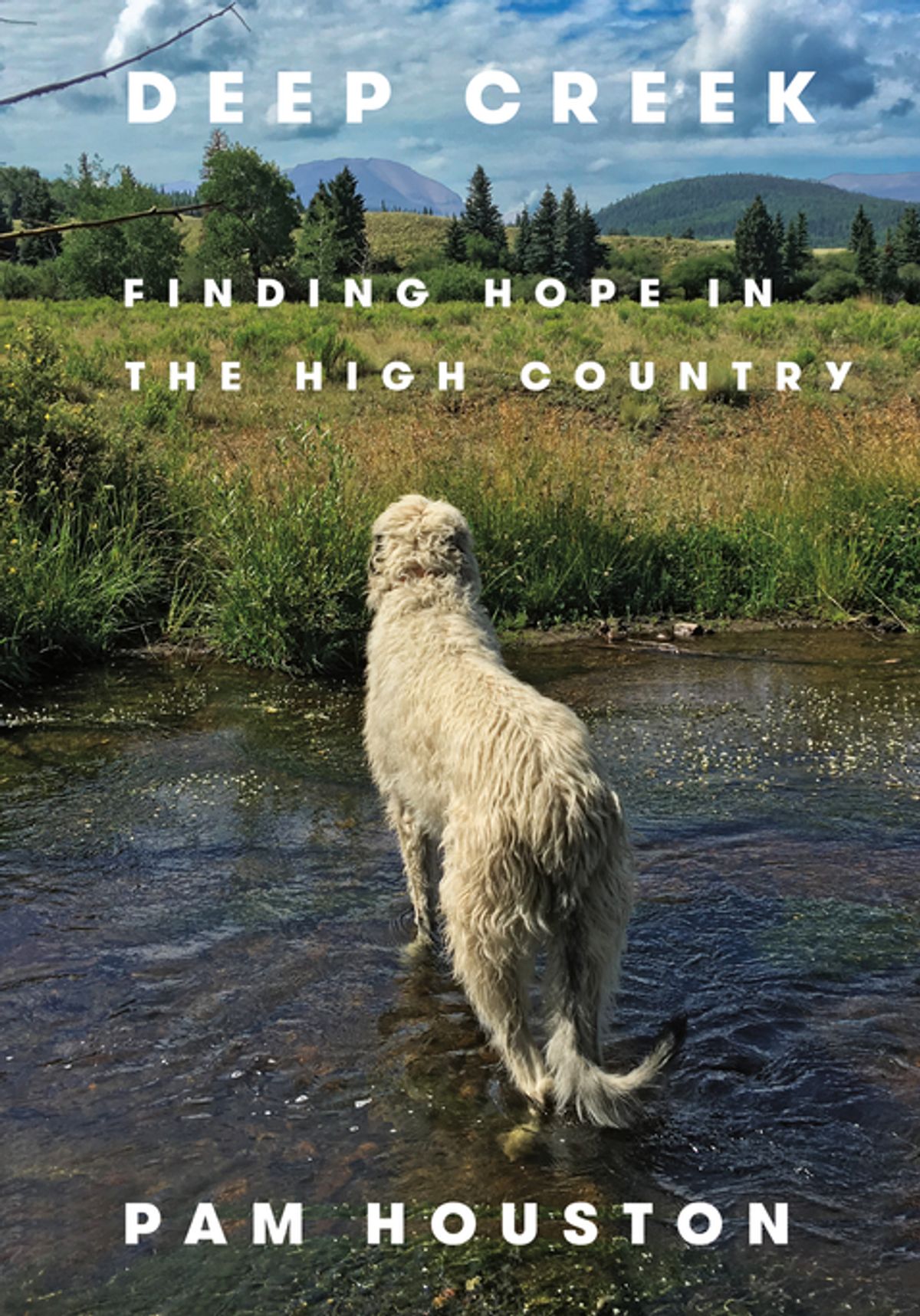

(Photo: Pam Houston)

To me, that’s the key to the healing. Knowing the ground and being able to describe it and honoring it that way is the healing process. That was true in a broader way when I first came out West and thought, This is the landscape that will heal me. And to this day, I don’t exactly know why. Something about the bigness of it, something about the cleanness of it, and the ratio of open land to people. In some ways, it’s the exact opposite of suburban New Jersey. But I can’t say why it was so healing and so cleansing. And I love so many places; I even love New Jersey in my own way. But when I get off a plane here, and step out into the Denver airport parking lot, my whole body relaxes. It’s something about the quality of the air, the quality of the sky.

You write about how the ranch heals you with its dailiness—the chores and the things that you have to do every day. I would venture to say that some of that healing quality is there in the writing: the soothing feeling of that routine and the way that comes across to the reader, just understanding the daily and the seasonal rhythms of your life.

Absolutely. The one thing I knew at the very beginning of this book was that the idea of an almanac or the idea of the 12 months—that there was a calendar here. Because that’s so much about the ranch. My childhood obviously was super unpredictable and irregular. One of the things that’s so healing is just, you know, you gotta get your wood by this date, you gotta get your hay by this date, and the daily chores, just going out and listening to the chickens cluck, whatever. The regularity is a comfort.

(Photo: Mike Blakeman)

I’m someone who likes change. I’m someone who likes to go, likes to see, likes difference. But the routine of the ranch and the schedule and the calendar, the almanac of the ranch, allowed me to cultivate this other side of myself.

Thinking about how long you’ve owned the ranch—we know so much more now about human-caused climate change, and our general outlook for the future has changed a lot, even just in the last year, even in the last—

Like two weeks, yeah.

Yeah. How has that evolving understanding changed your relationship with the ranch?

Well, we’re also in a real drought here in my part of Colorado. Yesterday I took a walk up on this place called Long Ridge. You should not be able to hike Long Ridge at this time of year at all. Last year it was dry enough, but this year, after a whole other year with nothing like enough precipitation, it was just desiccated. I find myself every day just fighting despair because it’s so tactilely visible here right now.

One of the places where all of this comes up in the book is in the “Diary of a Fire” section. There seem to be two different basic fears related to the fire. There’s the fear for the ranch itself, but then there’s the fear about what the fire will do to the landscape you love, and the idea of looking out at charred mountainsides. What has it been like living with the burn scar and starting to watch the regrowth over the last several years?

It’s much less sad than I thought it would be. Certainly these fires are climate change-driven, to a certain extent, but I’ve also learned that we were kind of due for this. It is not so unusual for spruce-fir forests to burn big every 150 or 200 years.

And the fact is, it’s beautiful. The new growth is strong. We’re going to have lots of new aspen forests, we’re going to have a lot of meadows we didn’t have—and I love a meadow. The animals have moved back in. I’ve hiked, literally behind my house, very often for the last five years, and the change is amazing. It’s quite marvelous, the recovery. It’s a beautiful thing to watch.

You’ve seen the beauty and the sheer resilience of the natural world up close in a way that a lot of people never really get to. Do you think that’s given you a different kind of hope?

(Photo: W.W. Norton & Company)

Well, I do have hope for the Earth. I can’t say I have hope that people will do the right thing on behalf of the Earth and we’ll be able to turn this thing around. But I have ultimate faith in the Earth’s ability to regenerate. We’re a species that has gotten out of control, obviously, and we are going to suffer for it. And we’re going punish the wrong people—not the ones creating the havoc. Because that’s what people do. And it’s going to be awful. I also think there’s ways to mitigate the suffering, and I hope that’s what we turn our attention to, as a country.

To come back around to the way that the book is partially built around the story of your childhood—I wonder if there are any lessons for coping with climate grief from the ways that the landscape has helped you deal with more personal kinds of grief.

That’s a really good question. I’ve written about this [more recently than the book], but [President Donald] Trump is so much like my father. I know that’s a ridiculous thing to say because I bet you there are a hundred thousand women who think that. But just so much about him, like the way he makes everything about money, and the way he twists things, and the accusing [others] of the thing that he just did. He has so much in common with my father, it’s so crazy. And I realize that we were in a lot of climate trouble before Trump. But his determination to harm every little good thing that [President Barack] Obama did for the environment—that particular determination feels so deeply personal to me, that when you say “climate grief” and “childhood grief”? It’s the same.

One of the things I came to in the book that really matters to me is the idea that we have to keep loving the Earth even in her distress. The difference between now and when I came out here and thought that the Earth was huge and there was wilderness everywhere and it was all untouched and it hadn’t been, you know, damaged the way I had been damaged by my father, and it could heal me and it could make me whole again—well, now you know, she’s been damaged by these same sorts of people. It’s so connected to me. You think about Trump and you think about all his [alleged] sexual assaults and the assault on the Earth, and it’s all the same frickin’ thing.

I do think it’s important to love the Earth in its broken form. That’s part of what I’m doing when I’m walking in the burn scar. The most awful thing we could do is turn away now and be like, Oh well, I’m just going to play video games, or, I’m going to watch videos of the Earth when it was beautiful. It’s so important for us to keep looking at her as she’s being destroyed by our own hand. That’s the only way we’re going to stay whole.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.