“For many of us, quicksand was once a real fear,” write the producers at Radiolab. “It held a vise-grip on our imaginations, from childish sandbox games to grown-up anxieties about venturing into unknown lands. But these days, quicksand can’t even scare an 8-year-old.”

Interviewing a class of fourth graders, writer Daniel Engber discovered that most understood the concept, but didn’t find it particularly worrisome. ”I usually don’t think about it,” said one. They were more afraid of things like aliens, zombies, ghosts, and dinosaurs. But they understood that it was something that people used to be afraid of: ”My dad told me that when he was little his friends always said ‘look out that could be quicksand!’”

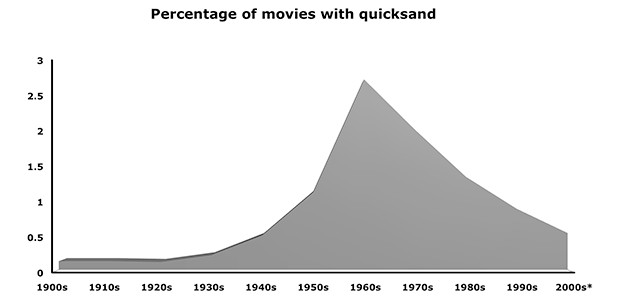

Engber became fascinated with what happened to quicksand. He found a source of data—compiled by, of all things, quicksand sexual fetishists—that included every movie scene that involved quicksand from the 1900s to the 2000s. Comparing this number to the total number of movies produced allowed him to show that quicksand had a lifecourse. It rose in the ’40s, skyrocketed in the ’60s, and then fell out of favor.

(Graph: Radiolab)

Why?

Engber found a pattern in the data. In quicksand’s early years, the movie scenes featured quicksand as a very serious threat. But, after quicksand peaked, it became a joke. In the ’80s, quicksand even made it into My Little Pony and Perfect Strangers. Later, in discussions about plot lines for Lost, the idea of quicksand was dismissed as ridiculous.

I guess it’s fair to say that quicksand jumped the shark.

In sociology, we call this the social construction of social problems: The fact that our fears don’t perfectly correlate with the hazards we face. In this case, media is implicated. What is it making us fear today?

This post originally appeared on Sociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner site, as “The Sinking of Quicksand.”