The trial took place in Fairbanks, Alaska, under the fluorescent lights of the northernmost Denny’s franchise in the world. It was January, cold and dark, and outside, the neon signage of a handful of chain outlets gleamed: McDonald’s, Subway, Wendy’s. Schaeffer Cox, the charismatic young leader of the Alaska Peacemakers Militia, was charged by the State of Alaska with failing to notify a police officer that he was carrying a concealed weapon. But Cox, a member of the sovereign citizen movement, did not recognize the Alaskan court’s authority over him. And so at Denny’s, he faced a “common law” trial by a handpicked jury of his peers: his fellow militia members, friends, and sovereign citizen believers. Cox was acquitted.

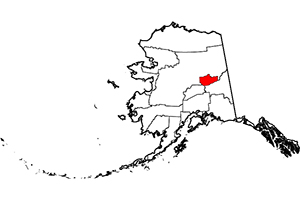

But within weeks of the proceedings at Denny’s, Cox and three of the jurors who acquitted him would be back in the court whose authority they denied. This time, instead of a weapons misdemeanor, Cox would be facing allegations that he had plotted to commit murder up and down Fairbanks North Star Borough, a county-like government unit home to nearly 100,000 residents. The case against him would be supported in large part by surreptitious recordings made by an FBI informant—a mole who was also among those sworn in as jurors that night at Denny’s, under those bright fluorescent lights.

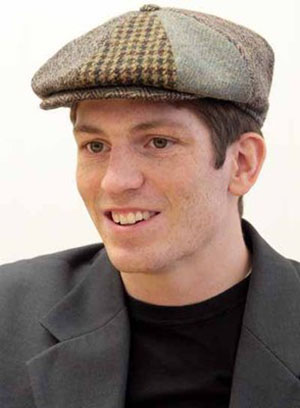

SCHAEFFER COX HAS CELTIC coloring—pale, freckled, with darker hair and brows—and a boyish face. Before being taken into federal custody, he was rarely seen without a distinctive tweed newsboy cap. In public speeches, he had a folksy tone and an easy laugh, and hints of a preacher’s cadence. He grew up in Colorado before moving to Alaska with his parents as a teen—his father, Gary Cox, is a Baptist pastor. Cox graduated from high school by correspondence in 2003, and spent some time studying at the University of Alaska-Fairbanks before starting a landscaping and construction business, according to the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. He married young and had a son, Seth Justice Argus Cox, in June 2008.

“We’ve got a 3,500 man force, militia force, in Fairbanks. It is not a rag-tag deal. I mean, we’re set. We’ve got rocket launchers and grenade launchers and claymores and machine guns and cavalry, and we’ve got boats. It’s all set.”

Two months later, at the age of 24, Cox entered the public political arena for the first time, as a challenger in a Republican state primary. He lost, but received 37 percent of the vote; he was also active in the Alaskan arm of Ron Paul’s 2008 presidential campaign. Then, in early 2009, Cox founded a gun rights group he called the Second Amendment Task Force—he would go on to organize several open-carry days in Fairbanks that year. He also founded the Alaska Peacemakers Militia, dedicated, he said, to preventing government overreach and protecting the citizens of the Fairbanks area in the event of a societal breakdown. As his profile grew, he traveled more frequently to the Lower 48, giving speeches to sympathetic groups there.

It was around this time that the Southern Poverty Law Center, the Anti-Defamation League, and the FBI began to take note. The Peacemakers landed on the SPLC’s watch list of anti-government groups within months of its formation, and Mark Pitcavage, a director of investigative research for the ADL, later acknowledged to the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner that they’d been keeping tabs on Cox, too. It was Cox’s combination of militia leadership and commitment to the theory of sovereign citizenship that raised red flags, he explained to reporter Jeff Richardson. “The fact that he was a two-fer, they’re much deeper into the movement,” Pitcavage said. “I knew he had a lot of talk in him. I didn’t know if he had much walk in him.”

Cox was certainly talking the talk. In a November 2009 speech to a small crowd in Montana, he boasted about his militia’s readiness for real combat. “We’ve got a 3,500 man force, militia force, in Fairbanks,” he said. “It is not a rag-tag deal. I mean, we’re set; we’ve got a medical unit that’s got surgeons and doctors and medical trucks and mobile surgery units and stuff like that. We’ve got engineers that make GPS jammers, cell phone jammers, bombs, and all sorts of nifty stuff. We’ve got guys with airplanes with laser acquisition stuff and we’ve got rocket launchers and grenade launchers and claymores and machine guns and cavalry, and we’ve got boats. It’s all set.”

Schaeffer Cox.

The claims seemed plainly ludicrous. The FBI, though, wasn’t laughing. The text of the speech landed on the bureau’s radar, and a pair of confidential informants were dispatched o see what Cox and the Peacemakers were up to.

SCHAEFFER COX’S LEGAL TROUBLES began in early 2010, just days after his 26th birthday. On March 1, Cox was arrested and charged with second-degree assault—his wife had reported to state troopers that Cox had punched and choked her during an argument while the couple were driving down the highway to Anchorage with their son. A few days later Cox accepted a deal, pleading guilty to a reduced charge of reckless endangerment, a misdemeanor, in exchange for two years of probation and a one-month suspended sentence. Less than two weeks later, he was back in police custody again.

Cox had other projects beyond the Second Amendment Task Force and the Alaska Peacemakers Militia. One of them was the Liberty Bell network, a group that monitored perceived abuses of police power and other rights violations—Cox claimed it had 7,000 members. On a Wednesday night in mid-March, he got a call from a Fairbanks homeowner who was familiar with the network. She believed the police were making an unauthorized search of her property, and she called on Cox for help. He arrived on the scene wearing a bulletproof vest and carrying a small knife and a concealed Ruger .380-caliber semiautomatic pistol.

The police had responded after receiving a 911 hang-up call from the residence, they told the News-Miner. The hang-up had triggered a safety protocol: The cops were authorized to do a walk-through of the home, without a warrant, to ensure that everyone inside was OK. The homeowner, though, denied that any 911 call had been made. According to police, when Cox attempted to enter the home where the police officers were working—whether to monitor their walk-through or to confront them about their presence is not clear—he was searched and the Ruger was found. He was arrested and charged with failing to notify a police officer that he was carrying a concealed weapon—another misdemeanor.

This second arrest launched Cox into a year-long legal wrangle marked by escalating paranoia and increasingly heated rhetoric. He was released on bail, but barred from possessing a weapon in the interim—he challenged that ruling, arguing that he wore body armor and carried a gun at all possible times because of the death threats he received. “Everybody’s going to think, ‘He’s not armed, so let’s go get him,’” he told the court, according to the News-Miner. Later, when the judge ruled that he could once again possess his weapons at home but could not carry them in public, he told her that the ruling would endanger his family.

In early April, with the case still pending, Cox met with about 40 members of the Second Amendment Task Force to discuss his recent arrests. He told the group that his initial arrest had been engineered by his vengeful mother-in-law, and that state troopers had fabricated the details in the charging documents. He called the Alaska State Troopers “wicked, corrupt and despicable,” according to the News-Miner, and added that the Office of Children’s Services had been harassing him since the incident on the highway to Anchorage.

Cox kept a fairly low public profile through the summer, but resurfaced in November with an interview on KJNP-TV in North Pole, a satellite community outside of Fairbanks. The lead-up to the TV spot had been tense—Cox told his core followers that he believed the government had dispatched a shadowy six-man hit squad from Aurora, Colorado, to kill him and his family. In response to the threat, he enlisted a half-dozen militia members to provide a security detail while he visited the TV station to film the interview. He told the crew to be ready to shoot to kill if the federal agents appeared. “They’re soulless assassins,” he told his team. “If we kill them, they’re not going to be missed. These guys aren’t supposed to be here. If one of them messes up and gets killed on the job, they just abandon them. They don’t exist.”

The group included Coleman Barney, a “major” in the militia and a mild-mannered Mormon electrician from North Pole; Barney came to the studio equipped with an AR-15 rifle, 160 rounds, and a 37mm grenade launcher loaded with a round known as a “hornet’s nest,” filled with rubber pellets. He and the rest of the group patrolled the streets around the studio in search of plainclothes agents—one local woman reported being stopped by a group of armed men and asked to produce identification.

Meanwhile, inside the station, Schaeffer Cox addressed his security situation in the televised interview itself, claiming that he could take out the team from Aurora any time he pleased. “With 3,500 guys we’ve got tremendous resources at our disposal,” he said. “We had those guys under 24-hour surveillance, those six trouble causers that came up here from the federal government. We could have had them killed within 20 minutes of giving the order. But we didn’t because they had not yet done it. It’s not right, they’re people too. And they’ve got just as much ability to repent as anybody else and there’s no sense in it.”

It was early December before Cox’s case was taken up again. In a brief hearing, Cox denied the court’s authority over him as a sovereign citizen. “I deny the Alaska Court System is the real judiciary,” he told the court, citing its income tax number and business license as evidence. “It’s a business.” He made reference to “soulless federal assassins” visiting Fairbanks as agents provocateurs—presumably a reference to the hit squad from Aurora—and suggested that the judge should be grateful he was willing to attend the hearing and have a reasonable discussion at all. “There’s a lot of people that would just as soon come and kill you in the night than come in your courtroom and argue during the day,” he told her.

At his next hearing, several days later, Cox attempted to serve the judge with a restraining order and other papers from his own “de jure court.” “You’re now being treated as a criminal engaged in criminal activity and you’re being served in that manner,” he said.

Outside, after the hearing, Cox told a police officer that the militia had the troopers “outmanned, outgunned and we could probably have you all dead in one night.”

AFTER A YEAR OF grandstanding and legal wrangling, the end game came in early 2011. On January 16, the Denny’s jury acquitted Cox on the misdemeanor weapons charge. In early February, several of Cox’s militia associates traveled to a convention in Anchorage and made arrangements to buy grenades and other illegal weapons, dealing—though they didn’t realize it then—with an FBI informant in the process. And on February 12, according to recordings made by a second FBI mole, Schaeffer Cox unveiled a retaliatory plan dubbed “2-4-1”: For every militia member arrested or detained, the plan called for two government officials to be kidnapped. For every militia member killed in combat with government agents, two government officials would be killed. And for every militia member’s home seized by the government, two government buildings would be burned. Government aggression would be the trigger, and the plan would be activated by a tweet from Cox’s Twitter account.

Cox’s official government trial on the weapons misdemeanor was set for February 14, Valentine’s Day. When he failed to appear, an arrest warrant went out: Schaeffer Cox was officially a wanted man.

Just over three weeks later, on March 10, residents of Fairbanks noticed large numbers of law enforcement agents on the move. Alaska State Troopers, U.S. Marshals, Fairbanks police department, the FBI—everyone was in on the action. This wasn’t just about a simple misdemeanor and a failure to appear anymore—by the time the dust had settled, Cox and four of his associates were in custody, and several homes had been searched top to bottom. The group faced an array of weapons-related charges and one major, central charge: conspiracy to commit murder.

“We had those guys under 24-hour surveillance, those six trouble causers that came up here from the federal government. We could have had them killed within 20 minutes of giving the order. But they’re people too. And they’ve got just as much ability to repent as anybody else and there’s no sense in it.”

THE MOLE WHO MADE the audio recordings that brought Cox and the Peacemakers down was Gerald “J.R.” Olson, a onetime trucker and drug-runner who became an FBI informant in hopes of earning a reduced sentence for operating a fraudulent septic tank installation business. Olson joined the Alaska Peacemakers Militia in August 2010 and soon found his way into their inner circle: He recorded the planning meeting for the security detail before the KJNP interview, and he was a juror at the Denny’s trial. He traveled to Anchorage with Lonnie Vernon, another militia member, Denny’s juror, and KJNP security team member, to purchase illegal weapons from arms dealer Bill Fulton—who was also, though Olson didn’t know it, an informant working the case. And he was present, and recording, as the 2-4-1 plan came into focus.

But the recordings soon became a problem. Arrested alongside Cox were Coleman Barney, Lonnie Vernon and his wife Karen Vernon, and Michael Anderson, an associate of the group but not a militia member. Anderson faced lesser state charges that suggested he’d gathered intel for Cox and monitored government employees on his behalf; Karen Vernon was initially charged with involvement in 2-4-1 but was later accused, alongside her husband, of an entirely separate scheme to murder the judge who’d been handling their income tax dispute. (The pair, as sovereign citizens, had been battling over unpaid back taxes.) The bulk of the 2-4-1 charges landed on Cox, Barney, and Lonnie Vernon.

Initially, Cox and co. faced a mixture of federal weapons charges and state-level charges of conspiracy to murder. But a state judge ruled that the clandestine FBI recordings, while legal under federal law, were inadmissible under Alaskan law because they’d been made without a warrant. The state charges were dropped, and all charges were dropped against Anderson, who received immunity in exchange for his testimony, but after a few months of legal back-and-forth, the conspiracy charge was re-introduced at the federal level. Cox, Barney, and Vernon were facing decades in federal prison.

The trial finally got under way in Anchorage in May 2012, more than a year after the 2-4-1 arrests. With their bail set in the millions, the defendants had remained in custody throughout the wait. It was a complicated affair: The prosecution had a list of more than 70 potential witnesses, and the case had accrued thousands of pages of documents and more than 100 hours of tape.

Fairbanks North Star Borough.

As the six-week trial unfolded, prosecutors led the jury through the FBI recordings made by Olson, past speeches by Schaeffer Cox—including the one that had attracted FBI attention—and testimony from Michael Anderson. Anderson told the court that he had created a database of home addresses of government employees for Cox: State Troopers, Fairbanks police officers, a worker at the Office of Children’s Services. He’d also had a listing of other government employees of interest: TSA agents, U.S. Marshals. He testified that he became concerned about why Cox wanted the information, and he never turned it over to his friend.

The defense argued that Cox, Barney, and Vernon had been entrapped by informants with ulterior motives—the suggestions to resort to violence, they claimed, had always come first from J.R. Olson or Bill Fulton, the moles. Olson had egged the group on in hopes of landing himself some leniency in his own case, they suggested. Cox’s attorney painted a picture of Cox as an innocent boaster, a man who liked to shoot his mouth off but didn’t, as the Anti-Defamation League’s Mark Pitcavage had put it, have “much walk in him.” The Peacemakers never had anything like 3,500 members, he acknowledged—35 might be closer to the truth. The group had never, he argued, had any murderous intent.

When Schaeffer Cox took the stand in his own defense, the trial veered occasionally into the realm of the absurd. The “hit list” referred to on his iPhone, he explained to the jury, was a compilation of great songs about freedom that he had been planning to put together. He had collected the home addresses of government employees because he’d been warned that they were in danger, and he wanted to pass that warning along to them at home, personally. His message, he explained, was based on the teachings of Gandhi, Mandela, and Martin Luther King, Jr.

Just talking about killing people is not enough to warrant a charge of conspiracy to commit murder. To convict, the prosecution had to establish that Cox and his men had taken steps to enact that conspiracy—and they pointed to the home addresses that had been collected, the efforts to acquire illegal weapons, and the presence of the armed security detail at the TV studio—apparently ready and willing to kill federal agents should they appear—as proof.

The jury deliberated for more than two days. In the end, Cox was convicted on the conspiracy charge and a handful of lesser weapons charges, as was Lonnie Vernon. In Coleman Barney’s case, the jury deadlocked on the conspiracy charge but convicted on the weapons charges.

Cox’s sentencing took months. In the meantime, Lonnie Vernon and his wife Karen pleaded guilty to plotting the murder of a federal judge; Karen Vernon was sentenced to 12 years, and Lonnie to a combined 26 years for both sets of crimes. Coleman Barney received five years. Finally, in January 2013, it was Schaeffer Cox’s turn.

At sentencing, Cox lost his cool for the first time. He broke down, fighting tears, and his attorney—a new one, as he’d fired the first after the guilty verdict—raised the issue of mental health for the first time, arguing that Cox suffered from paranoia and personality disorders. The judge, nonetheless, sentenced Schaeffer Cox to 26 years.

FEAR IS CORROSIVE, A slow-acting poison. Schaeffer Cox was afraid—of the Office of Children’s Services, of the courts and the police, of the supposed six-man death squad from Aurora—and he instilled that fear in his followers. Then, together, they set about making others afraid. One of the TSA agents targeted by the Peacemakers testified during the trial that she has since started carrying a gun herself, for protection. Another airport employee reported that Cox approached her at work, took her picture, and told her that he needed to identify “all the Nazis.” And meanwhile, everything the authorities did to rein in Cox and his men only made their followers more afraid, too, more convinced that there was truly something to be afraid of.

“I put a lot of people in fear by the things that I said,” Cox told the courtroom on the day of his sentencing. “Some of the crazy stuff that was coming out of my mouth, I see that, and I sounded horrible…. The more scared I got, the crazier the stuff. I wasn’t thinking, I was panicking.”

Almost a year later, in December 2013, a letter surfaced from Cox, sent to his supporters from prison back in July. In it, all traces of contrition were gone. “Dear Sensible People of a Candid World,” he wrote. “My name is Francis August Schaeffer Cox. I am a 29 year old husband and a father of two young children. I am a political prisoner in a secret Federal prison located in Marion, Illinois. I was sentenced to just under 26 years in prison on January of 2013. I haven’t done anything illegal and I certainly haven’t done anything morally wrong.”

Cox’s appeal of his sentence is pending.

We’re telling stories all week about people who opt out of society on some level—homesteaders, back-to-the-landers, anti-government survivalists. Read the entire series here.