At the end of 2011, Chesapeake Energy, one of the nation’s biggest oil and gas companies, was teetering on the brink of failure.

Its legendary chief executive officer, Aubrey McClendon, was being pilloried for questionable deals, its stock price was getting hammered and the company needed to raise billions of dollars quickly.

The money could be borrowed, but only on onerous terms. Chesapeake, which had burned money on a lavish steel-and-glass office complex in Oklahoma City even while the selling price for its gas plummeted, already had too much debt.

In the months that followed, Chesapeake executed an adroit escape, raising nearly $5 billion with a previously undisclosed twist: By gouging many rural landowners out of royalty payments they were supposed to receive in exchange for allowing the company to drill for natural gas on their property.

In lawsuits in state after state, private landowners have won cases accusing companies like Chesapeake of stiffing them on royalties they were due. Federal investigators have repeatedly identified underpayments of royalties for drilling on federal lands, including a case in which Chesapeake was fined $765,000 for “knowing or willful submission of inaccurate information” last year.

Last month, Pennsylvania governor Tom Corbett, who is seeking re-election, sent a letter to Chesapeake’s CEO saying the company’s expense billing “defies logic” and called for the state Attorney General to open an investigation.

McClendon, a swashbuckling executive and fracking pioneer, was ultimately pushed out of his job. But the impact of the financial maneuvers that he made to save the company will reverberate for years. The winners, aside from Chesapeake, were a competing oil company and a New York private equity firm that fronted much of the money in exchange for promises of double-digit returns for the next two decades.

The losers were landowners in Pennsylvania and elsewhere who leased their land to Chesapeake and saw their hopes of cashing in on the gas-drilling boom vanish without explanation.

People like Joe Drake.

“I got the check out of the mail … I saw what the gross was,” said Drake, a third-generation Pennsylvania farmer whose monthly royalty payments for the same amount of gas plummeted from $5,300 in July 2012 to $541 last February. This sort of precipitous drop can reflect gyrations in the price of gas. But in this case, Drake’s shrinking check resulted from a corporate decision by Chesapeake to radically reinterpret the terms of the deal it had struck to drill on his land. “If you or I did that we’d be in jail,” Drake said.

Chesapeake’s conduct is part of a larger national pattern in which many giant energy companies have maneuvered to pay as little as possible to the owners of the land they drill. Last year, a ProPublica investigation found that Pennsylvania landowners were paying ever-higher fees to companies for transporting their gas to market, and that Chesapeake was charging more than other companies in the region. The question was “why”?

ProPublica pieced together the story of how Chesapeake shifted borrowing costs to landowners from documents filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, interviews with landowners, people who worked for the company and employees at other oil and gas concerns.

The deals took advantage of a simple economic principle: Monopoly power.

Boiled down to basics, they worked like this: When energy companies lease land above the shale rock that contains natural gas, they typically agree to pay the owner the market price for any gas they find, minus certain expenses.

Federal rules limit the tolls that can be charged on inter-state pipelines to prevent gouging. But drilling companies like Chesapeake can levy any fees they want for moving gas through local pipelines, known in the industry as gathering lines, that link backwoods wells to the nation’s interstate pipelines. Property owners have no alternative but to pay up. There’s no other practical way to transport natural gas to market.

Chesapeake took full advantage of this. In a series of deals, it sold off the network of local pipelines it had built in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Louisiana, Texas, and the Midwest to a newly formed company that had evolved out of Chesapeake itself, raising $4.76 billion in cash.

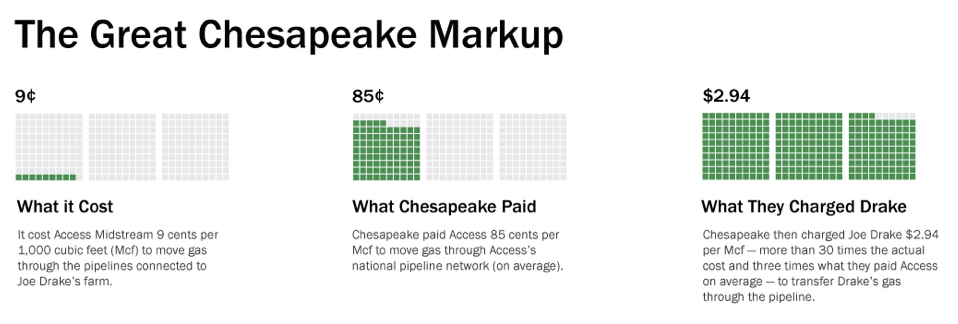

In exchange, Chesapeake promised the new company, Access Midstream, that it would send much of the gas it discovered for at least the next decade through those pipes. Chesapeake pledged to pay Access enough in fees to repay the $5 billion plus a 15 percent return on its pipelines.

That much profit was possible only if Access charged Chesapeake significantly more for its services. And that’s exactly what appears to have happened: While the precise details of Access’ pricing remains private, immediately after the transactions Access reported to the SEC that it collected more money to move each unit of gas, while Chesapeake reported that it also paid more to have that gas moved. Access said that gathering fees are its predominant source of income, and that Chesapeake accounts for 84 percent of the company’s business.

What’s more, SEC documents show, Chesapeake retained a stake in the gathering process. While Chesapeake collected fees from landowners like Drake to cover the costs of what it paid Access to move the gas, Access in turn paid Chesapeake for equipment it used to complete that process, circulating at least a portion of the money back to Chesapeake.

ProPublica repeatedly sought comment and explanations from both Chesapeake and Access Midstream over the course of several months. Both companies declined to make executives available to discuss the deals or to respond to written questions submitted by ProPublica.

Days after the last of the deals closed, Drake and other landowners learned the expense of sending their gas through Access’ pipelines would eat up nearly all of the money they had been previously earning from their wells. Some saw their monthly checks fall by as much as 94 percent.

An executive at a rival company who reviewed the deal at ProPublica’s request said it looked like Chesapeake had found a way to make the landowners pay the principal and interest on what amounts to a multi-billion loan to the company from Access Midstream.

“They were trying to figure out any way to raise money and keep their company alive,” said the executive, who declined to be named because it would jeopardize his dealings with Chesapeake. “I think they looked at it as an opportunity to effectively get disguised financing … that is going to be repaid at a premium.”

AT 54, JOE DRAKE guns his six-wheeler up a steep rock-rutted trail on the backwoods of his 494-acre tract and points to his property line, marked by a large maple in a sea of indistinguishable trees. He knows where it lies, because as a kid his father made him walk that line to string barbed wire. The wire is long gone, but a rusted snag remains entombed in the bark. Back then, the Drakes ran a dairy farm in these pastures.

“It’s just something you’ve got in your blood that you do,” Drake said. “But dairy farmers are a dying breed…. It was a good way of life.”

Today, the milking stalls have been ripped out of a long barn that still carries the stench of their manure, but stores 20-foot stacks of bailed hay instead. Drake sold all 187 head of cattle two years ago, pinched by regulated milk prices and the rising costs of independent farming. He took out a second mortgage to keep the farm afloat.

Across the road, past his house and just beyond a stand of oak and ash, the hillside’s natural shape transitions to a steep slope of pushed dirt, capped by a seven-acre flat the size of a large gravel parking lot. In the middle stands a six-foot stack of steel pipes and valves—a gas well.

When Chesapeake arrived at Drake’s door, he was optimistic. Drake plastered a “Drill, baby, drill” bumper sticker in the window of his Ford F-250 pickup. He welcomed the chance to draw an easy income from his land, and was unswayed when his neighbors raised questions about the environmental risks of drilling. Chesapeake promised Drake one-eighth the value of whatever it made from his well. It seemed like a fair deal.

If any driller was going to make money for Drake, he thought, it would be Chesapeake. The company had built an empire off finding and drilling natural gas discoveries as the fracking boom rolled across the country. With uncanny foresight, its founder, McClendon, locked up exclusive access to immense tracts of land across the country by promising property owners that their lives would be transformed by the wealth the gas under it would bring.

Then the company drilled furiously—in Oklahoma, then Texas, Louisiana, and later in Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale—catapulting itself to the rank of second-largest producer of natural gas in the United States. It made McClendon—who snatched up a stake in the Oklahoma City Thunder basketball team and moved into a stone mansion in the posh Oklahoma City suburb of Nichols Hills—one of the richest men in the world.

McClendon—named by Forbes in 2011 as “America’s Most Reckless Billionaire”—would find his way into plenty of personal trouble. He took a personal stake in Chesapeake’s wells, and then liquidated his stock in the company in order to cover his own losses, rattling investors and ringing corporate governance alarm bells. He drew scrutiny for selling his $12 million antique map collection to the company and ire for taking a $75 million bonus as Chesapeake struggled.

In 2012, he borrowed as much as a billion dollars from the company’s private equity partners to fund his private interests. Separately, an investigation by Reuters alleged Chesapeake had rigged land leasing prices in Michigan, under McClendon’s direction, sparking a federal criminal probe.

But McClendon’s overarching design for the business nonetheless made it a formidable player. Chesapeake aggressively pursued business opportunities beyond its drilling. It created interlocking businesses and took advantage of tax breaks that deliver out-sized benefits to energy companies.

By structuring itself this way, Chesapeake earned a slice of profit from each step. Chesapeake’s subsidiaries trucked the drilling materials, drilled the wells, fracked the gas, gathered and piped it away to a hub, and then marketed the end product—what economists call vertical integration. In fact, he built Chesapeake into a powerhouse, an echo of the old Standard Oil empire, positioned to control almost every variable and armed with the leverage to get its way.

Neither McClendon nor his staff responded to requests for comment for this article.

From early on, the company viewed the local pipelines as a profit source. Chesapeake formed subsidiaries to build and run the lines, then spun them off into a separate, publicly traded company. That company would eventually evolve into Access Midstream, when Chesapeake sold its shares—one of the three deals—for $2 billion in 2012.

The strategy paid dividends. At Chesapeake’s headquarters, a group of new, distinctively-designed office buildings went up, with views south over the state capital and the city’s small skyline. The company lavished its employees with perks, too. “They’ve got a 72,000-square-foot gym, free trainers … free Thunder tickets,” said Andrea Watiker, who scheduled pipeline capacity for gas traders in one of the company’s new towers.

Confident he was in good hands, Drake endured the trucks, dirt, and noise that accompanied gas drilling and signed agreements that allowed Chesapeake to run pipelines across his fields. To transport the gas from Drake’s well, Chesapeake built a pipeline that stretched south from within spitting distance of the New York border, cutting a wide swath through the forest. Then it went down beyond the white-spired church in Litchfield, and ran some 35 miles further to its handoff at the Tennessee interstate pipeline near the Susquehanna River.

What Drake didn’t know at the time was that the pipeline was more than a way to move his gas to market. It would become part of a strategy to make more money off of Drake himself.

WHEN THE FIRST GAS flowed from the well on Drake’s land in July 2012, it was abundant, and the royalty checks were fat. “We was hoping to get these loans paid off … with the big money,” said Drake, who earned more than $59,400 from the first few months of production, referring to the mortgages on his farm.

That year, many Pennsylvania landowners began receiving similarly sized payments as thousands of new wells—many of them drilled by Chesapeake—finally began producing gas. Pennsylvania fast approached Texas as the largest source of natural gas in the country, and with it, the prosperity long promised to this rural part of the United States seemed about to arrive.

But then, in January 2013, without warning or explanation, the expenses withheld from Chesapeake’s royalty checks for use of the gathering pipelines tripled. Drake’s income dwindled. His contract with Chesapeake—and Pennsylvania law that sets a minimum royalty share in the state—promised him at least 12.5 percent of the value of the gas. Drake says the company led him to believe any expenses would be negligible. “Well, they lied.”

A few miles away, the same month, his brother-in-law had 94 percent of his gas income withheld to pay for what Chesapeake called “gathering fees.” Others across the northern part of the state also saw their income slashed. “I’ve got a stack,” said Taunya Rosenbloom, a lawyer representing Pennsylvania landowners with natural gas leases. She pulled the statements of all of her Chesapeake clients into an eight-inch pile on her desk. “Everyone is having this issue.”

Drake found the statements Chesapeake mailed him each month mystifying. He pored over the papers, hired a lawyer, compared notes with his neighbors, but couldn’t make sense of the charges.

Other Pennsylvanians were similarly baffled. Sometimes, Chesapeake charged different fees to neighbors whose wells fed into the same gathering line. Other times, companies that had partnered with Chesapeake on the same well charged vastly less for expenses. No one at the Chesapeake could seem to explain how the charges were set.

“There is no rhyme or reason why one client would have such an exorbitant amount taken out when another no more than three miles away has only 20 percent of their royalty taken,” said Harold Moyer, an accountant in Bradford County, Pennsylvania, who represents more than 150 landowners with royalty rights. Moyer said he saw a dramatic difference between what Chesapeake usually charged compared to other energy companies in the area.

Different contracts may entitle Chesapeake to charge varying amounts. Some of the leases examined by ProPublica limit a landowner’s share of expenses to 12.5 percent—or the same as their share of the proceeds. Other contracts prohibit Chesapeake from withholding any expenses at all. Drake’s contract appears to allow Chesapeake to recoup as much money as it wants; it stipulates that he can be charged for the expense of gathering and transporting his gas without specifying his share of such expenses.

Gas drillers differ significantly in how much they charge landowners for expenses. The Norwegian energy company Statoil owns a portion of the gas extracted from Drake’s well, as well as a portion of the gathering line that moves the gas to an interstate pipeline. Yet Statoil rakes off virtually nothing for its expenses, according to its statements. Statoil told ProPublica that it sells its gas independently and makes decisions about billing separately from Chesapeake.

“When it comes to deciding which, if any, deductions are appropriate, we make that assessment according to the terms of each lease and the applicable laws,” wrote Ola Morten Aanestad, in an emailed response to questions.

Drake peers out the window, over the hills that descend from his porch into a valley brightening with the changing colors of fall, and scowls. He can’t stand being indoors. He’s worried that he’ll spend most of next hunting season here at this table, trying to decipher Chesapeake’s statements. His monthly gas statements pile up, unorganized, on the kitchen table, below a rack of deer antlers and beside two empty cans of Coors Light and a camouflage baseball cap.

Drake’s gathering pipeline only extends a few dozen miles, far less distance than the interstate pipeline it feeds into that carries his gas through New Jersey toward White Plains, New York. Yet public documents filed with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission show it only cost about $0.38—on average—to move a unit of gas on the interstate system—a fraction of the $2.94 Chesapeake charged Drake to move a unit of gas a vastly shorter distance that February.

“Nobody can tell you why or how come,” Drake said. “They pass the buck, they tell you to call this person, and you are lucky if you can even get an answering machine.”

Chesapeake declined to explain its charges to Drake or to ProPublica. When a ProPublica reporter visited Chesapeake’s headquarters in Oklahoma City, the company’s director of external communications sent a message that he was “booked solid” and couldn’t talk.

THERE HAS LONG BEEN dispute over how drilling companies calculate royalty payments due landowners.

A 2007 report commissioned from a forensic oil and gas accountant by the National Association of Royalty Owners (NARO)—an organization representing landowners in their dealings with the oil and gas industry—found that almost every company it examined had “used affiliates and subsidiaries to reduce income to royalty owners and taxing authorities.”

Nine out of 10 of the top producers in Colorado, Texas, Arkansas, and Oklahoma—including ConocoPhillips, Chevron, BP, and Chesapeake—had used subsidiaries to sell their gas for significantly more than the amount they reported to landowners, according to the report. They inflated their expenses, too—at least according to the six companies that provided that level of detail for the report—charging landowners, on average, 43 percent more than what they actually paid to handle the gas. (Neither Chevron nor Chesapeake provided information about their expense deductions.)

ConocoPhillips and BP declined to comment for this article. Chevron did not respond to a request for comment.

Other companies have been ensnared in similar controversies. The giant pipeline company, Kinder Morgan, which also declined to speak to ProPublica, has been accused by Montezuma County, Colorado, of overstating its transportation and other expenses, and underpaying $2 million in taxes as a result. (Kinder Morgan has paid that bill, but is appealing the decision.) Chevron has faced multiple lawsuits for underpaying royalties and overstating expense deductions because of alleged self-dealing through its affiliate relationships, including a 2009 case the company settled with the U.S. Department of Justice for $45 million.

“Every company has been involved,” said Jeffrey Matthews, a vice president and forensic accounting expert at Charles River Associates, a consulting firm, in a lecture to landowners and oil and gas industry accountants in Houston. “If you’re dealing with related parties,” the technical term for the sort of inter-locking subsidiaries created by Chesapeake, “the costs can be double, or triple. You don’t know if you are paying for something two to three times over.”

Even so, Chesapeake stands out among its peers and is widely known to interpret contracts to match its strategies, executives in the oil and gas industry say.

The company has faced numerous lawsuits—filed by the billionaire Ed Bass, and the city of Fort Worth, among others—claiming it misrepresented its expenses. Chesapeake has paid hundreds of millions of dollars in settlements and judgments in such cases, including a $7.5 million settlement with Pennsylvania landowners last fall.

One Oklahoma lawsuit, brought by other oil companies that had partnered with Chesapeake, alleged that Chesapeake cheated them out of the final sales price of their gas and artificially inflated its operating expenses, in part by folding in the salaries of high-level management, the cost of seminars they attended, and rent and office expenses for field offices. The suit was settled in late 2004 for $6.5 million. Chesapeake denied any wrongdoing, and the settlement explicitly states that Chesapeake did not agree to “change the practices complained of” in the lawsuit.

“They were making excessive, unwarranted, and unauthorized charges,” said Charles Watson, an Oklahoma attorney involved in the case. “I don’t think it’s mistaken interpretation, I think it’s an intentional accounting maneuver to reduce the amount of money going to the royalty owners and increase the amount of money going to the operator.”

Chesapeake declined to comment about the case.

For Drake to know how Chesapeake calculated his gathering costs, he has to pay lawyers and accountants to audit the company, or take his grievance to arbitration, a process that would cost him tens of thousands of dollars. In either case, he would need to see the purchase agreements that describe the company’s gas sales in detail. They list far more precisely than Drake’s own statements exactly what costs were incurred, how much gas might have been lost along the way or used by the company for its own purposes, what marketing fees Chesapeake’s subsidiary charged, and the final, real price of the gas.

But Chesapeake isn’t required to share these agreements. They are proprietary.

“When it comes to production expense,” said Charles River’s Matthews, “you’re at their mercy.”

THE DEALS THAT LED to much higher expense charges for Drake and his neighbors involve some sophisticated financial engineering.

Over 12 months, Chesapeake sold off a significant portion of its nationwide system of gathering pipelines in three separate transactions. By December 2012, almost all of the pipes were controlled by a single company—Chesapeake’s former affiliate, Access Midstream. Taken together, the sales brought $4.76 billion in cash into Chesapeake’s coffers.

The reason behind the moves was simple: All that profligate spending—the Oklahoma City offices, corporate jets, and huge executive salaries—had come at roughly the same time that the price of gas tumbled to historic lows, analysts at several Wall Street investment firms told ProPublica. Chesapeake “desperately needed cash,” observed Tony Say, who once headed Chesapeake’s Marketing division—the same part of the company that now handles transportation for the gas.

In its securities filings, Chesapeake said that the deals brought the company $1.76 billion more than it had invested to build and maintain its pipelines and the companies that ran them, leaving the impression that the sales were an unqualified boon for Chesapeake.

But a look at an SEC filing by Access Midstream tells a different story: Chesapeake was going to have to give much of that money back.

On the same day as the last of the major sales, Chesapeake signed long-term contracts pledging to pay Access a minimum fee for transporting its gas. In some cases, the fee held no matter what happened to the price of gas, or even how little of it flowed out of Chesapeake’s wells.

Chesapeake also promised to connect every new well it drilled to Access’ lines for the next 15 years in Ohio’s Utica Shale, a potentially lucrative emerging drilling field, and made similar agreements elsewhere.

According to ProPublica projections based on figures disclosed by the companies in late 2013, Chesapeake’s commitments would have it paying Access a whopping $800 million each year. Over 10 years, the contracts would generate nearly twice as much money as Access had paid Chesapeake for its businesses in the first place.

In plain words, Chesapeake and a company made up of its old subsidiaries were passing money back-and-forth between each other, in a deal that added little productive capacity but allowed both sides of the transaction to rake in billions of dollars.

Access’ chief executive, J. Mike Stice, told a group of investment banking analysts last September that the deals amounted to a “low-risk business model” that “most people haven’t understood.”

“Nobody really has the access to contractual growth that [Access Midstream] has,” Stice said. “It doesn’t get any better than this.”

The SEC filings provide other detail about the ways that the two companies devised to remain inextricably linked, even though Chesapeake has sold the stake it once had in Access.

At the same time it signed its contracts, Access pledged to subcontract a slice of its business back—again—to companies still owned by Chesapeake. It also agreed to buy industrial equipment used to compress the gas for the pipelines from a company owned by Chesapeake. In essence, Chesapeake would get a rebate on the fees it had guaranteed to Access. Chesapeake never answered questions about whether that rebate was figured in to the price it charged Joe Drake and his neighbors.

In its royalty statements to Joe Drake, Chesapeake says the expenses it had deducted reflect what it costs the company to move his gas. The company has said in public statements about the royalty disagreements in Pennsylvania that it is merely recouping its costs.

But ProPublica’s projections drawn from figures previously reported by both companies show that Chesapeake could earn back billions of dollars of the transportation fees it is paying Access over the next 10 years.

There are other ties between the two companies. Access’ chief executive, Stice, once worked for McClendon as the chief operating officer of one of the companies that used to run the pipelines. Chesapeake’s chief financial officer, Dominic del Osso, sits on the board of Access Midstream Partners, and as of 2011, according to SEC records, owned thousands of shares of Access stock.

The relationships raise questions about Chesapeake’s assertions that its contracts are arm’s-length agreements, and that its expenses reflect its true cost of operating.

“They had a lot of disguised debt,” said Philip Weiss, a chief investment analyst with Baltimore Washington Financial Advisors, who has covered Chesapeake over the years, and was often concerned that the company has understated its financial obligations. In this case, he said, Chesapeake’s expensive contracts with Access might not just be the cost of operating, but another unusual long-term financial obligation that would weigh down the company, but which wouldn’t be reflected in the normal measures of debt. “The use of off-balance-sheet debt is often a way to try to avoid getting as much investor scrutiny.”

For six months Chesapeake declined to answer questions about these discrepancies posed by ProPublica. But in its latest annual financial filings made public just two weeks ago, Chesapeake noted for the first time that it had $36 billion worth of what it called “off-balance-sheet arrangements,” including $17 billion of long-term commitments to buy gathering services. This appears to be the first time the company has acknowledged that it owes more money than what has been identified as debts in previous SEC filings.

In the filings, Chesapeake said that the $17 billion figure didn’t include reimbursement from royalty owners, and that landowners and corporate partners alike “where appropriate, will be responsible for their proportionate share of these costs.”

In an earlier, September 2013 quarterly filing, there were hints of the same activity, but with no disclosure of the salient details to shareholders that might help them understand what was really going on. Chesapeake reported that its expenses related to its pipeline and marketing business roughly doubled in the months after it sold its pipelines, compared to the same period a year earlier, and that its revenues for that part of its business also increased accordingly, covering the new costs. Chesapeake told investors it had cost the company more than $8 to transport a cubic foot of gas or its oil equivalent—an astronomical amount unheard of in the energy industry.

“Something is wrong with this calculation,” said Fadel Gheit, a seasoned industry analyst for the investment firm Oppenheimer, who estimated the figure was off by a decimal point before later confirming that it matched the numbers Chesapeake had reported to the SEC. “It can’t be.”

In fact, none of the financial analysts who cover Chesapeake that ProPublica spoke with could explain the explosion in Chesapeake’s marketing and transportation revenues and expenses using oil sales alone.

“The change in marketing, gathering, compression revenue and expense is staggering,” wrote Kevin Kaiser, a financial analyst with Hedgeye, a private equity group in New York, in an email to ProPublica.

Neither Chesapeake’s investor relations group, nor its media staff, would comment on whether the deals amounted to disguised debt that landowners would repay. In interviews, one former Chesapeake employee with knowledge of the company’s operations dismissed the notion that Chesapeake was essentially paying back an off-balance-sheet loan by paying unusually high fees for use of the pipelines.

“The timing supports that—that Chesapeake got paid a lot of money and the gathering fees get paid back over time, and it looks like a loan arrangement,” said the former employee. “But to jump to the conclusion that the whole thing is a sham and a means by which they are going to defraud royalty owners is not true.”

Only in its latest filing at the end of February, after months of queries from ProPublica, did Chesapeake add a note—two sentences in 299 pages—stating that its contracts with Access and other companies played into the rising figures. But the company did not specify how much.

And to the extent that the real costs of gathering and transporting gas can be gleaned from securities reports and Joe Drake’s own statements, there’s still a big gap between what Chesapeake reports it paid out, and what Access reports it received for gathering services.

In the mean time, one thing is for sure: all the escalating costs, side deals, and unexplained debt aside, Access is making more money than ever, while Chesapeake—so recently fighting to stay alive—has emerged from its troubles and is turning a profit.

Joe Drake, on the other hand, is almost back to where he began.

He recently canceled a fishing trip to Canada and doubled back on the question of how to make a living from the farm. With his livestock gone he will now focus on growing and bundling hay, which he will sell to other farms so they can feed their animals. The natural gas boom has become little more than a sideshow.

“We are surviving,” he said. “But we learned that a good old handshake don’t cut it anymore.”

This post originally appeared on ProPublica as “Chesapeake Energy’s $5 Billion Shuffle” and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.